Imagine the weight of another person’s skin against your own. Not draped loosely like cloth, but pressed intimately, wetly, the residual warmth of their final heartbeat seeping through to your flesh.

Now imagine wearing it for twenty days as it rots.

Eating in it. Sleeping in it. Blessing children in it whilst the tissue liquefies in the spring heat and fluids leak down your arms.

This horror unfolding is not fiction. It’s a true story.

The God Who Shed Himself

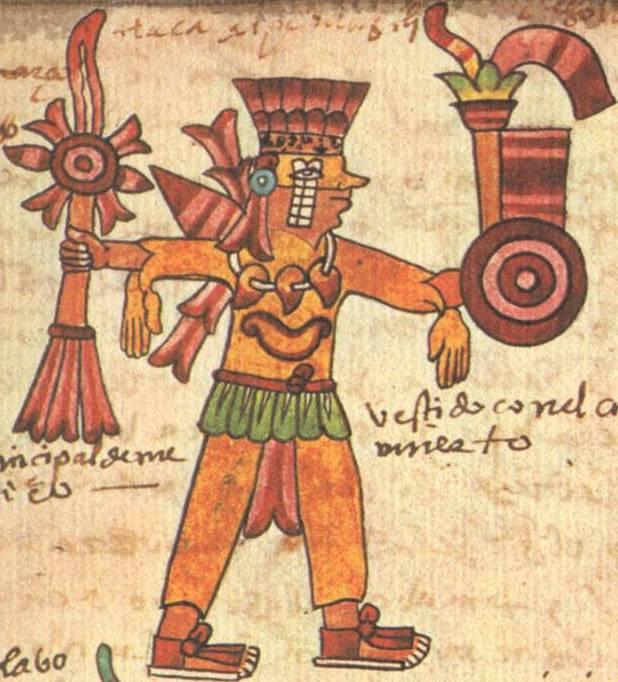

In late March, across the cities of the Aztec Empire, the festival of Xipe Totec began. “Our Lord the Flayed One” was the god who renewed the world by peeling away its skin, the divine force behind spring’s reawakening.

The mythology was straightforward and utterly nightmarish: Xipe Totec had flayed himself to feed humanity, shedding his golden skin so that the world might live.

Now humanity must return the favour via the flaying ritual.

Ancient stone carvings show a figure whose living face peers through the slack mask of a corpse, the carved mouth gaping where dead lips no longer meet, eyes gleaming with divine purpose from within a shell of decay. The carving is a replica of what transpired. This is true ancient horror in its most terrifying form.

To the Aztecs, life was a cycle of nourishment and sacrifice. The earth had to be fed if it was to feed in return.

The Aztec gods had torn themselves apart to make the world. Now, humans must return that gesture to keep it alive.

The Flaying

Captives, usually enemy warriors taken in battle, were washed and perfumed until their skin gleamed.

They were adorned as the god himself, draped in gold and turquoise, transformed into living idols. They were not mocked. They were exalted, elevated beyond mortality for the brief time they had left. A small positivity within the dismal truth of what was about to happen.

To these individuals, their death would come in the most gruesome way: the Aztec human skin ritual.

A Knife Like A Razor

On the stone altar, an obsidian blade sharp as volcanic glass opened the chest in one perfect movement.

You could hear the crack of ribs.

The wet gasp of failing lungs.

The heart, lifted to the sky, still beating, quietly stilled by the priest’s hands.

The body remained warm. That warmth mattered.

Skilled Hands Skinned The Man Quickly

Then came the flaying. Skilled hands, trained through years of apprenticeship, worked with surgical precision. The incisions followed ancient patterns: down the back, along the limbs, around the face. The skin had to come away in a single, unbroken sheet.

Any tear would ruin the sacred garment.

The priest separated flesh from muscle with careful scraping motions, peeling the dermal layer away whilst the blood still ran warm, whilst the tissue remained supple enough to work with.

It took time. Concentration. Reverence.

Afterwards, The Aztec Priests Wore Human Skin

When at last the skin lay complete, glistening and whole, the priest stepped into it.

He pulled it on as one might don the most sacred of robes, working his arms through the arm holes, his legs through the leg holes.

The previous owner’s hands dangled from his wrists like obscene gloves. The face sagged across his own features, a second expression worn over the first.

It clung to him. Warm. Heavy and intimate.

For a moment, just a moment, it felt alive. As the Aztec priests wore human skin, they took on the hope of the Aztec people that they would have a good harvest.

Hundreds Of Priests Were Doing The Same Thing

He had become Xipe Totec. But he was not alone. Across the empire, in Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Zempoala and dozens of other cities, hundreds more priests were performing the same ritual. Hundreds of men stepping into freshly flayed skin, pulling the faces of the dead across their own features.

And for the next twenty days, they would walk among the living.

Life in Rotting Flesh

The priests moved through the cities openly. They blessed fields, pressing their decaying hands into the soil. They healed the sick, touching foreheads with fingers that were not their own.

They forgave debts, speaking through lips that had once belonged to someone else.

Priests Kissed Them With Decaying Lips

Children were brought forward by their parents.

Held up to be kissed by the lips of the rotting mask.

The priests embraced them, leaving traces of putrefaction on small cheeks. And the families gave thanks.

They did not remove the skins to eat. They did not take them off to sleep. For twenty complete days and nights, the priests lived inside another man’s dead skin as it rotted.

The Stench Of Decaying Flesh

The smell must have been unimaginable. In the spring heat of central Mexico, human skin begins to decompose rapidly. Within days, the tissue would have started to liquefy, sloughing away in patches. Within a week, the bacterial bloom would have created an odour so thick you could taste it, a mixture of sweet rot and ammonia that clung to everything.

As the skins loosened, they had to be adjusted. Retied. Held in place with cords.

Fluids leaked constantly.

Their Human Skin Faces Grimaced As They Walked

The faces began to slide from their proper positions, distorting into expressions that had never existed in life. Eye holes stretched. Mouths gaped wider. The boundaries between priest and skin blurred into something neither fully human nor entirely divine.

Yet no one recoiled. The stench of death was not profane. It was holy. The putrefying skins, loosening day by day, symbolised the earth itself casting off the husk of winter. The more they decayed, the nearer the world came to its promised rebirth.

You walked past them in the market. These rotting ambassadors of renewal. You smelled them before you saw them. You watched them bless your neighbour’s child, watched the skin of their hands crack and weep as they made the sacred gestures.

You brought them offerings. Bowed before them. Kissed the ground where they had walked.

They Were Saved From Starvation

Because the alternative was unthinkable: a world where spring did not come, where seeds remained locked in dead soil, where the gods turned their faces away and let humanity starve in an eternal winter.

The skins were called teocuitlaquemitl, “golden clothes”. They were dyed yellow, transforming grey-white dead flesh into something that gleamed in the torchlight, something that looked almost divine. The colour symbolised fertility, the promise of maise, the gold of a successful harvest.

When at last the twenty days ended, when the skins had rotted to the point where they could barely be distinguished from the priests beneath, the garments were removed with the same reverence that had marked their donning. They were placed in special containers, sealed tightly to contain the overwhelming stench, then stored in chambers beneath the temples.

The divine flesh given back to the gods.

Renewal complete.

What Archaeology Reveals

In 2019, archaeologists working at the Ndachjian-Tehuacan site in Puebla made a breakthrough: the first complete temple dedicated solely to Xipe Totec. Built by the Popoloca people between 1000 and 1260 AD, the temple complex revealed the full horror of the rituals.

Two circular altars stood at the top of stone steps.

One was used for the sacrifice itself.

The other for the flaying.

The sculptures discovered are stunning yet eerie masterpieces made of volcanic rock. Two massive skull-like carvings, each over 200 kilograms, depict the flayed face of a god with unsettling precision, featuring calm expressions and parted mouths as if breathing through another’s mask.

The torso is haunting. The stone carving features a figure with an extra hand from one wrist, a remnant of a stolen body. The back showcases intricate engravings of the god’s sacrificial skins, while a hole in the belly would have held a green stone used in ceremonies to “bring it to life.”

Whoever carved these understood precisely what they were depicting.

They had seen it.

They had stood close enough to observe how dead skin settles across living bone, how the features distort, how the eyes peer out from holes that were never meant to frame them.

Excavations have also revealed specialised obsidian blades worn smooth from use, their edges microscopic in sharpness. Tests on similar blades demonstrate that these blades could cut through human skin with almost no resistance.

The Aztecs had perfected the technology of flaying.

The Twisted Logic

To modern minds, it seems monstrous. Yet to the Aztecs, the horror was sacred precision. They did not worship pain for its own sake. They worshipped balance, the cosmic equilibrium that kept the people fed. Respecting the seasonal changes.

Wearing another’s skin was not desecration.

It was communion.

The merging of the mortal and the divine is profound. The priest, bound in rotting flesh, symbolises renewal: the shimmering divinity beneath decay and the living self emerging from the old—death as a transformation.

Every time a priest stepped into that rotting flesh, he was performing a cosmic drama of death and resurrection.

When at last the priests shed those final, liquefied folds of skin, when they stepped free and washed the residue from their bodies, the crowd rejoiced. The god had renewed himself and proved once more that death leads to rebirth.

The earth would live again. Spring would come. The maise would grow.

The Echo

The festivals ended after the Spanish conquest, as colonial administrators were horrified by them. Temples were demolished, and sacred spaces were desecrated. The last priests to wear flayed skins practised in secret before the tradition faded away.

What remains are the carvings, excavated bones, and accounts from chroniclers that still make people uncomfortable five centuries later. In museums across Mexico, the stone faces of Xipe Totec gaze from their cases, mouths agape and eyes peering through once-fleshy masks.

You cannot honestly imagine it. Not really. Not in your bones. You cannot conjure the smell, the texture, the psychological weight of wearing another’s skin until it rots away. You cannot place yourself in a crowd that watched this and called it holy.

Yet it happened. All in the name of ritual.