Explore how the Aztecs’ collective faith powered their empire—where sacrifice, psychology, and belief kept the sun rising. A modern look at ancient ritual.

When it came to Aztec beliefs, everyone knows about their love of human sacrifice and the removal of a still-beating heart. But what else is there to know about what they believed?

The Altars Of Aztec Torture

When we look at the city below the altars of torture, we have to ask ourselves, what on earth was going on here?

Two distinct and very accurate realities.

The altar reeked of iron and decay. Blood splashed into channels carved into stone, pooling in basins where it blackened under the relentless Mexican sun.

The secretly hostile Spanish conquistadors gagged at the stench. Their eyes drank in the scenes before them. Human hearts piled like stinking meat, offerings they were told to the gods, and oh, there were so many gods to appease.

Human skulls arranged in neat rows, the sweet-sick smell of decomposition mixing with incense. The Spanish invader Hernán Cortés himself wrote, with a shaking hand, that the devil himself could not have conceived a more hellish scene.

Then they descended into the city proper and held their breath for an entirely different reason.

The Aztec Paradise

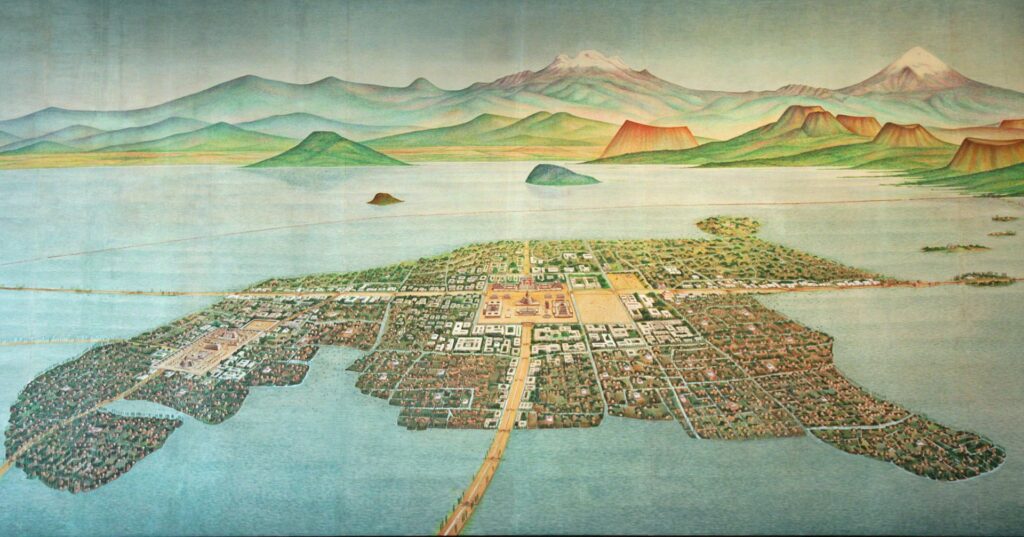

Tenochtitlan sprawled before them like a fever dream of civilisation. The city appeared to float on turquoise water that mirrored the sky, its white stone pyramids catching the golden morning sun like beacons.

Causeways stretched across the shimmering lake, connecting an island metropolis that dwarfed anything in Spain. The streets were swept cleaner than Madrid’s finest boulevards. Floating gardens bloomed with scarlet dahlias and white magnolias, their roots trailing in crystal-clear canals.

The primary market bustled with 60,000 traders daily, their stalls overflowing with emeralds, jade masks, iridescent quetzal feathers, jaguar pelts, and cacao beans. Dark, rich cacao beans piled high in baskets, their scent thick as chocolate and soil. So precious, they served as currency.

Palaces rose in perfect symmetry, their walls painted vermillion and deep azure. Aviaries housed birds of every colour. Parrots, living jewels, squawked and flew about like angels, hummingbirds with throats of molten copper glinting in the sun.

The ruler’s zoo kept jaguars and eagles. Aqueducts carried sweet water from distant springs. Public latrines lined the causeways, their waste collected for fertiliser.

Even the conquistadors – men who’d come seeking gold and glory for Spain – admitted they’d never witnessed such splendour. They were undoubtedly in awe, but also a little jealous.

They wanted this paradise, but it came with a disturbing truth. The bodies, the skulls, the horror that apparently gave them this paradise.

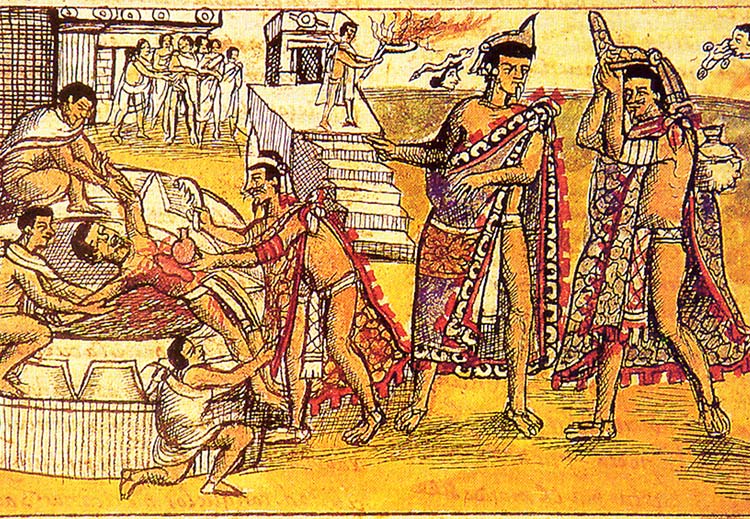

This was the impossible equation: a civilisation built on human sacrifice had created one of the world’s most sophisticated cities. The same hands that tore out beating hearts had engineered floating gardens that fed a quarter million people.

The priests who conducted ritual killings also maintained libraries of pictographic books painted in gold leaf and cochineal red, and schools where noble children learned poetry, astronomy, and rhetoric beneath frescoed ceilings.

And it worked. For two centuries, the Aztec Empire expanded. The rains came on schedule, filling the lake with silver light. Maise grew tall and green in the chinampas. The sun rose each dawn, seemingly satisfied with its payment in blood, painting the volcanic peaks purple and rose. Their universe held together through pure conviction – or did it?

Were the gods real, actually sustained by the hearts offered up on those reeking altars? Or had the Aztecs discovered something more unsettling – that absolute belief, shared by millions, could bend reality itself.

That faith so total it accepts human sacrifice might generate its own power, manifesting abundance through sheer collective will?

Was this the power of positive thinking, group collective and sheer belief?

When Tenochtitlan fell in 1521, it wasn’t just a city that died. It was an experiment in the furthest reaches of faith — proof that believing something strongly enough, together, might make it true.

Was this the power of gods, or the manifestation of minds that completely gave themselves to a shared reality?

The Spanish saw both truths at once: paradise floating below an abyss of hell. They never reconciled the contradiction.

It makes you think — and if you do, be careful what you wish for. Belief, after all, has a way of making itself real, apparently.