They did not hang a man and walk away.

No, for an executioner, that would waste an opportunity.

For centuries, the gallows was not only a place of punishment; it was a burgeoning marketplace. Once the body swung still, the real business began.

Executioners, both dreaded and indispensable, earned meagre official pay, but the condemned came with perks. Their corpses were property, and property could be sold.

The Rope Trade

In sixteenth-century Germany, Nuremberg’s official executioner Frantz Schmidt (1555–1634) recorded three hundred and sixty-one deaths and almost three hundred and fifty floggings in his meticulous journal, kept between 1573 and 1617.

His notes reveal the economy of death in full: payments not only for executions but for the rope, the clothing, even the blood-soaked straw beneath the scaffold.

It seems a taste for horror is not new!

A few inches of hanging rope could fetch a small fortune. By the seventeenth century in London, a length of Jack Ketch’s rope was thought to cure headaches and bring gamblers’ luck.

Fragments were sewn into coats or carried in pockets as charms against misfortune. At Tyburn, the hangman himself would slice and sell them, coiling the pieces like sacred relics.

Superstition, after all, was a sound business.

Skin and Bone

The trade did not end with rope.

Human skin, tanned and cured, became one of Europe’s most unsettling commodities.

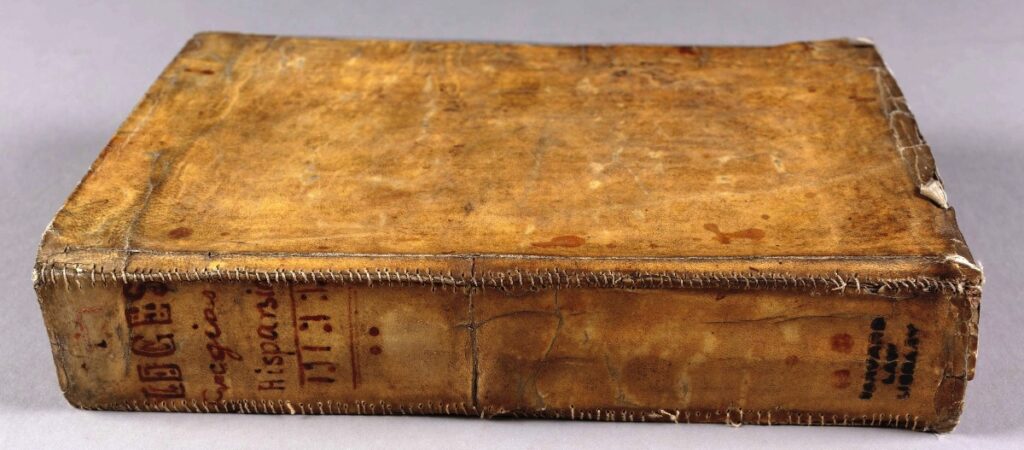

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, small strips of what was called executioner’s leather were used to bind knives, drums and even books. One notorious example, confirmed by DNA testing in 2014, still sits in Harvard’s library, its cover quite literally human.

People carried wallets or talismans made from the skin of the executed, believing that because the flesh had already “paid for sin”, it could not be tainted again. Moral logic turned inside out.

A Profitable Profession

Across Europe, the hangman was both outcast and artisan.

The Sanson family of France held the office of royal executioner for six generations (1688–1847). Charles-Henri Sanson, who guillotined Louis XVI in 1793, came from a line that treated death as trade, cleaning blades, selling rope, and managing bloodied tools like inventory.

Executioners were craftsmen in death and entrepreneurs in its aftermath. Some, like Schmidt, sought social respectability through detailed record-keeping. Others, like Ketch, became infamous, their names synonymous with death itself.

The Fat of the Dead

Human fat, axungia hominis, was another by-product with a brisk trade. In early modern Europe, it appeared in apothecaries’ lists and pharmacopoeias such as the Pharmacopoea Augustana (1564). “Hangman’s grease”, as it was known, was rendered from executed bodies and sold as a cure for gout, bruises and rheumatism.

In parts of Germany and the Low Countries, executioners’ families quietly profited from the sale of their remains, filling small jars labelled as medicine. A spoonful of death, rubbed into the skin.

From Relic to Reality

These souvenirs—rope, skin, fat—were relics of a world where justice and magic overlapped. The hangman was not merely an agent of punishment but a keeper of sacred contagion. Touching the rope or carrying the skin was to brush against the border between worlds.

By the nineteenth century, industrial medicine and private executions ended the trade. Yet belief lingers longer than law. As late as the 1920s, folklorist Edward Lovett, in Magic in Modern London (1925), found East End dockworkers and market-sellers still carrying scraps of “hangman’s rope” for luck.

Old magic dies hard.

The Final Twist

When London’s last public hanging took place in 1868, crowds still reached for relics: a splinter of wood, a scrap of rope, anything that had brushed death.

Because in the end, death was never merely punishment.

It was an opportunity for those who dared to get close enough.

Hungry for more?

Love this story? Check out The Groom of the Stool: The King’s Most Intimate Servant — where duty meant wiping the royal bottom, and discretion was paid in gold.