During one of the most trying times in history, when many fled, Dr Guy de Chauliac stayed. Angel? Foolish, brave or heroic, you decide.

This is his story.

The Black Death: Avignon, France – January 1348

In the plague pits of Avignon, archaeologists found skeletal remains with Yersinia pestis DNA preserved in the teeth, evidence of the bubonic plague that ravaged the city in 1348.

These were the people Guy de Chauliac tried to save.

Guy was born around 1300 in Chauliac, France, to a peasant family. Dirt poor. The kind of poor where becoming a physician was impossible. This little boy saw otherwise, and he was right. The lords of Mercoeur saw something in the boy and funded his education.

Not only funded, but literally poured funds his way.

He studied at Toulouse, then at Montpellier, Bologna, and Paris, every great medical school in Europe.

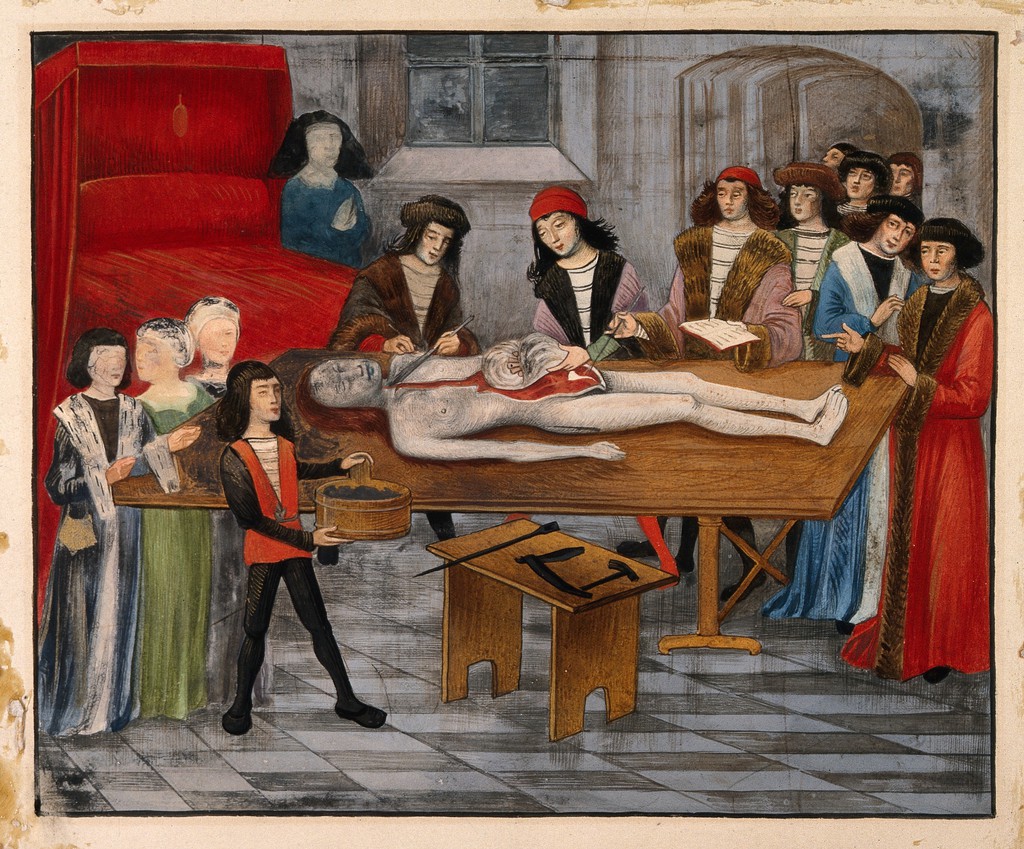

He learnt anatomy by dissecting corpses and mastered surgical techniques under the best teachers of his age.

By the 1340s, he had become the personal physician to Pope Clement VI at the papal court in Avignon, the most prestigious medical position in Christendom. He would also go on to serve several other Popes throughout his career.

But de Chauliac never forgot where he came from. In his writings, he emphasised that physicians should care for their patients’ total well-being, health, dignity, and fears. He had heart and he cared. Medicine, he believed, was a sacred duty, not merely a profession.

He had no idea what was coming and how he would be tested.

The Plague Arrives

January 1348. The Black Death reached Avignon.

This was no ordinary illness. It was apocalyptic. In London, it killed between thirty and fifty per cent of the population; in some regions, the toll was even higher. The black death struck fast: an incubation period of two to six days, then three to five more until death. People went to bed healthy and were dead by week’s end.

The symptoms were medieval nightmare fuel, fever, buboes (swollen lymph nodes in the groin, armpits, neck), blackened skin, vomiting, and the stench of rotting flesh while you were still alive. Between half and nine-tenths of those infected died.

And it was everywhere, all at once, as if the world were ending. Guy de Chauliac watched society disintegrate. He later wrote: ‘Father would not visit son, nor son, father; charity was dead, and hope prostrate.’

The bleakness was palpable.

Families abandoned their own sick children. Priests refused last rites. Most of Guy’s fellow physicians fled the city.

Those who stayed felt, in his words, ‘useless and ashamed, since they did not dare visit the sick for fear of infection; and when they did visit them, they could do very little and accomplished nothing.’

Nothing worked, not bloodletting, not herbs, not prayer. Patients died whether you treated them or not. Guy watched hundreds perish, powerless to save them.

But he kept going back.

The Fear That Stayed With Him

Why didn’t he run?

‘And I, to avoid defaming my reputation, did not dare to flee,’ he wrote. Not because he was fearless. Not because he thought he’d survive. But because he couldn’t live with himself if he abandoned his patients. He saw the humanity in their suffering.

‘With constant fear, I protected myself with the preceding methods as much as I could.’

Picture it: you’re a physician in 1348. Each morning you wake and check your body for the swelling that means death, armpits, groin, neck, because five of your eighteen colleagues are already gone. You know the odds.

And then you go to work anyway.

You walk into rooms where people are dying, where the air smells of decay, where families refuse to enter. You examine, you touch, you try remedies you know will fail. And at night, you go home and recheck yourself.

Guy de Chauliac did this every day for seven months.

Two hundred mornings of terror. Two hundred nights of searching for buboes. Two hundred days amongst the dying, knowing he could not save them, and that he would probably be next.

‘Towards the end of this mortality, I developed a continuous fever with a bubo in my groin.’

There it was, the swelling he had dreaded. Hot, painful, growing. He had the plague.

The Healer Becomes the Patient

After everything, after staying when others fled, after treating hundreds, after seven months of unrelenting fear, Guy de Chauliac was going to die like the rest. He accepted his fate.

His bravery and kindness had taken him.

‘I was sick for almost six weeks, and I was in such danger that my friends believed that I was about to die.’

Six weeks of fever, pain radiating through his groin and leg. He treated himself as best he could, softening the bubo with figs and cooked onions ground up with yeast and butter, then lancing it.

The papal physician, the man who had risen from poverty to the pinnacle of medieval medicine, reduced to cutting into his own infected flesh.

For six weeks, he lay waiting to learn if he would live or die.

‘By softening and treating the sore, as I have said, I escaped death by the command of God.’

He survived.

Against all odds, against a mortality rate of up to ninety per cent, Guy de Chauliac lived.

What He Left Behind

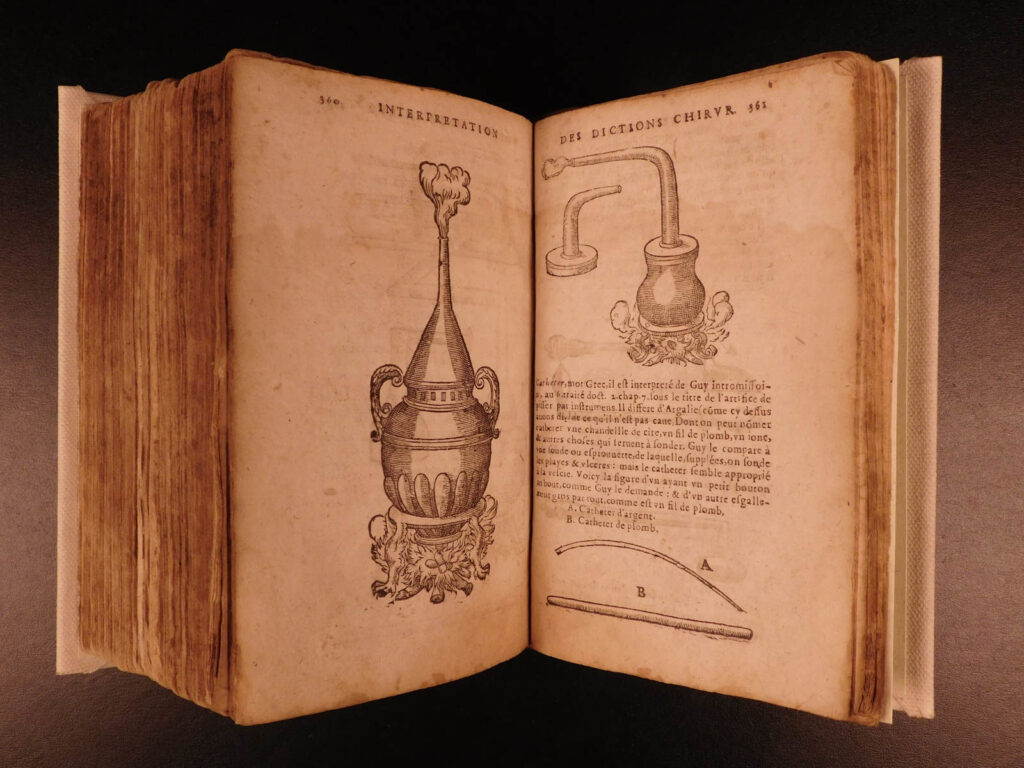

Over the next fifteen years, he wrote Chirurgia Magna (The Great Surgery), completing it in 1363. He poured into it everything he had learnt decades of study, years of practice, and the hard-won knowledge from those seven months in hell.

The book was translated into English, French, Dutch, Italian, and Irish. It went through seventy editions and remained the standard surgical textbook for over three centuries.

He turned his suffering into something that would save lives for generations.

The skeletal remains in Avignon’s plague pits still tell the story: Yersinia pestis DNA in tooth pulp, lesions on bone, the physical toll of disease etched into calcium and marrow.

These were Guy’s patients. The ones he could not save, but instead he sat with them at their darkest hours. He admitted his treatments had accomplished nothing. But he tried day after day.

The bodies were buried with care: oriented east-to-west according to Christian practice, some covered with charcoal to absorb the fluids of putrefaction, many with coins and trinkets from their former lives. Even in the midst of an apocalypse, the living preserved dignity for the dead.

And Guy was there, walking amongst them, treating them, staying when he could have run.

One thing is for sure: his days were not without fear, yet he continued on; this speaks to bravery.