Archaeologists found 16 attendants possibly sealed alive with Lady Fu Hao, China’s warrior queen. What made them obey?

The Anguished Ordeal Begins

Lady Fu Hao And Her Sixteen Slaves

For weeks, the attendants had watched their mistress decline, each laboured breath a countdown they dared not acknowledge. They probably swapped pointed looks, fiddled with their clothing and wondered how to escape.

There is a terrible kind of despair when you know your fate, the one you might not have chosen, is sealed.

The pumping adrenaline would have given way to hyper-focus, a state where routine becomes magnified. Noises, hair braiding, and smells become more pronounced.

The fear would have led to the slaves feeling as though they were floating above their bodies, perhaps detached.

Some slaves would have slipped into a calm reframing of what was happening to them. This was honour, this was what they had been made for.

Lady Fu Hao, Yinxu, c. 1200 BCE

In the palace chambers at Yinxu, capital of the Shang Dynasty around 1200 BCE, sixteen servants moved through their duties with growing dread. They braided Lady Fu’s hair with trembling fingers.

They prepared meals she could no longer eat. They burned offerings to their ancestors, their hearts sinking and their hopes dwindling when they were met with silence.

And they knew with a certainty that made their hands shake as they poured her wine. That once Lady Fu died, they would follow.

The day Lady Fu Hao stopped rising from her bed, sixteen lives ended with her.

But Who Was This Woman?

The Woman Who Commanded Armies

Lady Fu Hao was no ordinary royal consort.

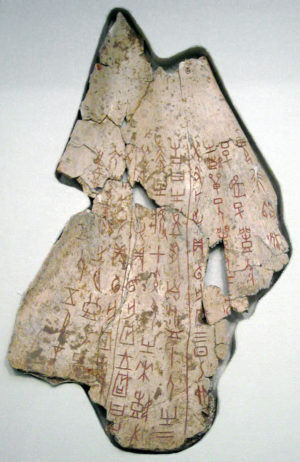

While King Wu Ding maintained approximately sixty wives, Fu Hao alone appears in oracle-bone inscriptions more than two hundred times, with an extraordinary prominence in China’s earliest written records. She was a high priestess. She practised oracle-bone divination, reading messages from the gods in the burn lines of tortoise shells, which was the birth of Chinese script.

She Led Armies And Conquered Where Men Had Failed

She was a military general who led thirteen thousand troops against the Qiang and Tu-Fang tribes, returning victorious where men had failed.

The king consulted her on matters of war and divination. When she spoke, even generals listened.

Her attendants knew this power intimately.

They had dressed her in bronze armour before battles. They had cleaned blood from ritual vessels after sacrifices. They understood that serving Fu Hao meant standing in the shadow of someone who conversed with ancestors and commanded the living. She was larger than life, commanding respect and fear in all she met.

Now that the end was near and the shadow was lengthening, it would soon consume them all entirely.

When Your Master Dies, So Do You

In Shang cosmology, death was not an ending but a transition. The deceased joined their ancestors in the spirit realm, a mirror world where hierarchies remained intact and the dead required the same comforts as the living. Kings needed advisors. Generals needed soldiers. And powerful women needed their household staff.

This was not metaphorical. It was literal, absolute, and terrifying.

The attendants knew the theology well—they had participated in enough funeral rites to understand. When nobility died, their servants followed through with renxun, or retainer sacrifice, ensuring the deceased would not arrive in the afterlife diminished or alone.

To many, this was a proud idea, an honour, but we are, after all, human and for some, honour didn’t feel quite right.

The Countdown To Death: When There’s Nowhere to Run

Imagine being eighteen years old, a handmaiden who has served Lady Fu Hao since childhood. You know how she takes her tea. You know which ritual songs calm her during divinations. You’ve braided her hair a thousand times, your fingers learning the rhythm of her breathing.

Now those breaths are shallow, irregular. The physicians have left. The priests perform their divinations with grim faces. Everyone knows what’s coming.

Your fate is sealed.

Do you run? Where would you go? Your family gave you to the palace as tribute, so they cannot protect you. The city gates are watched. Besides, attempting to flee would humiliate your entire household, possibly resulting in execution for them as well.

You Might Beg Or Plead To Not Die

Do you beg? Perhaps some did. Perhaps they pleaded with the priests, with other nobles, with anyone who might intervene. But the religious machinery of the Shang Dynasty was absolute.

To deny a noblewoman her attendants in death would be to doom her spirit, to disrupt the cosmic order. Then you realise that your life was never your own, it always belonged to her. It was your miserable fate, like it or not.

Lady Fu cannot Drink Or Eat Anymore, And Neither Can You

So you wait. You perform your duties. You bring Lady Fu her water, but she cannot drink. You burn incense in chambers that reek of approaching death. And with each passing day, the terror crystallises into something more challenging, colder. The numb acceptance of the inevitable.

These slaves, mostly women, followed their leader in death, but that was not the end; their bravery or devotion was not forgotten.

The Bones Don’t Lie: Sixteen Who Had No Choice

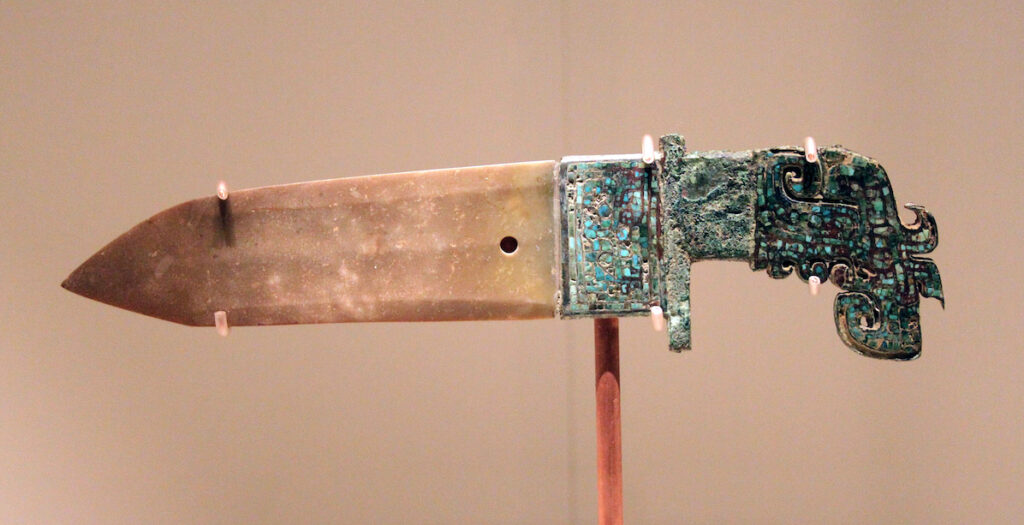

When archaeologists uncovered Tomb M5 at Yinxu in 1976, they found Fu Hao’s burial intact—a stunning discovery in a field plagued by millennia of grave robbing.

Among hundreds of bronze vessels, jade ornaments, and ivory carvings lay the skeletal remains of sixteen human attendants.

A Wonderful Gathering Of Talented People Lay Silent

Osteological analysis revealed that most were young women, though several skeletons were too damaged or fragmentary to determine sex with certainty. Perhaps some were male servants, musicians, guards, or ritual assistants. Each brings their own special training or talent. Their laughter forgotten, their quirks buried, their very humanness wiped away.

They Were All Murdered

What the bones do tell us is simpler and more chilling: these people were killed and placed in the tomb with their mistress. Whether they accepted their fate with religious resignation or died in terror, the archaeological record cannot say. But we can reasonably assume that, faced with certain death, at least some felt fear.

Ancient Ritual Killing

The attendants were laid in careful arrangement—some near Fu Hao’s coffin, others in different sections of the tomb. This wasn’t chaos. This was a ritual, planned and executed with religious precision. Each person had a designated place in death, just as they had in life.

This Is What Happened That Day

The funeral preparations are underway. Fu Hao’s body has been dressed in jade and bronze. The tomb chamber, a massive undertaking carved from earth, is ready.

A mix of clay, earth and reverence would have filled the air. Which probably felt stifling.

The attendants are gathered. Perhaps they’ve been given wine to calm them. Perhaps priests have spent days preparing them spiritually, assuring them of the honour awaiting them in the afterlife.

But honour is a word that sounds hollow when you’re eighteen years old and watching the tomb entrance that will become your grave.

They Watched Each Other Die

The tomb was arranged to replicate Fu Hao’s household. Her bronze vessels, used for ritual wine and offerings, surrounded her. Weapons marked her status as a general. Jade ornaments signified her rank. And the attendants, handmaidens, cooks, musicians, ritual assistants—were positioned around her in careful arrangement.

Six dogs were sacrificed as well, perhaps to guard or comfort their mistress in the afterlife.

Buried Alive

Imagine being one of the last conscious attendants as workers begin filling the tomb with earth.

The light from the entrance shaft grows dimmer. The air thickens. You can hear the sound of dirt falling, heavy and rhythmic, like a heartbeat counting down to silence.

You are surrounded by the dead. Your mistress lies silent in waiting. Your fellow servants and friends are now silent too.

Were any still alive when the final shovelful fell? It is known that many were buried alive. An inexplicably horrifying death to endure.

When did darkness become absolute and permanent? The archaeological record cannot tell us. But the possibility haunts the imagination.

The tomb was sealed with rammed earth and timber.

You Are Dying, But Life Goes On Above You

Above it, the living continued their rituals, making offerings to Fu Hao’s spirit and the spirits of her attendants. In Shang’s belief, they had crossed into the shadow world, where they would serve her forever—brewing tea for a ghost, braiding hair made of smoke, performing duties in an eternity that stretched before them like an endless corridor.

They had been slaves in life. Now they were slaves in death, with no hope of release, no possibility of escape. Forever.

Sixteen Graves, No Names, No Escape

By the Zhou Dynasty, which succeeded the Shang around 1046 BCE, such practices had been outlawed. Wooden and clay effigies replaced living sacrifices, a recognition that perhaps the dead did not require quite so much blood to maintain their dignity.

But for the sixteen attendants of Fu Hao, this reform came too late.

When archaeologists brushed earth from their bones in 1976, they uncovered one of China’s most significant historical discoveries. Fu Hao, once thought mythical, was proven real, a woman who commanded armies and communed with gods, whose name was written in oracle bones and whose tomb held treasures of immeasurable cultural value.

Hao was a hero, a figure to be reckoned with.

Yet among those treasures were the remains of sixteen people whose names we will never know. Mostly young women, the evidence suggests, though some remains were too damaged to identify with certainty. People whose lives were spent maintaining the comfort of power and whose deaths were spent maintaining its dignity.

They appear in no inscriptions. They commanded no armies. They left no mark except their bones, arranged in careful rows, and the horrifying question that lingers across three thousand years:

In those final moments, as earth filled their lungs or poison stilled their hearts, did they believe they were fulfilling a sacred duty? Or did they die knowing they were simply the human cost of someone else’s immortality?

Lady Fu Hao Is One Of China’s Greatest Treasures

The tomb of Lady Fu Hao remains one of China’s greatest archaeological treasures. But walk through any museum displaying her bronze vessels and jade ornaments, and remember: you are also looking at a grave.

Sixteen graves, to be precise. Sixteen lives erased so that one woman would not enter eternity alone. They might have felt forgotten, but today we see them and what they endured.

They, too, were brave.

The attendants served Fu Hao in life with braided hair and ritual wine.

They serve her still, in silence and darkness, forever.

Excavation Notes

Site: Tomb M5, Yinxu (Anyang, Henan Province, China)

Date: 1976

Lead Archaeologist: Zheng Zhenxiang, Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

Findings: Over 700 artefacts including bronzes, jades, and ivories; 16 human and 6 canine sacrifices