Aztec Period: c. AD 1300 to 1521

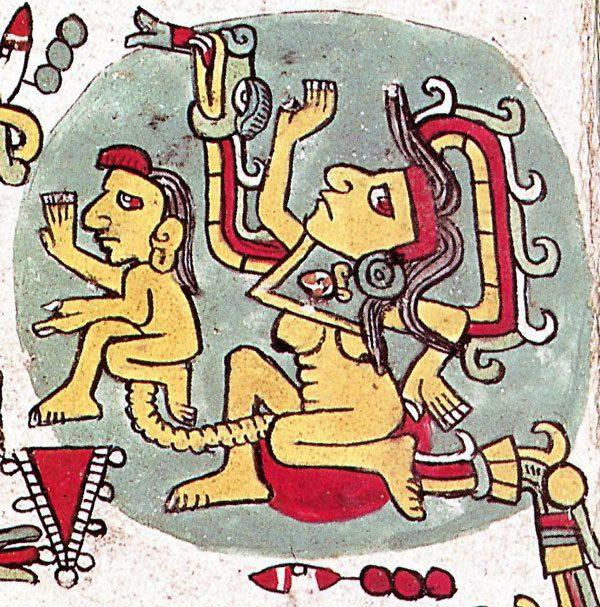

The Aztec culture is characterised by contradictions, featuring fearless warriors alongside a profound awareness that the cosmos could collapse if rituals were not performed correctly. There is a stark contrast between the extreme brutality of sacrificial altars and the beauty of their poetry, visual arts, and expressions of love and marriage.

By day, the Aztec world carried a kind of heaviness that is difficult for a modern reader to imagine. Priests tended the sacred fires, constantly aware that the sun was counting on the general population to keep it in the sky. That included how they behaved and the sacrifices they made.

Marriage and how it was handled were all a part of this.

The Aztec people lived inside the Fifth Sun, the final age, and nothing about it felt secure. If rituals failed or social order wavered, the sun might falter, darkness might swallow the world, and life could end at any moment.

Warriors were born, they fought and were hardened by the tasks they had to accomplish daily, but love existed, and in fact, it blossomed. Romance was alive and well in the city of Tenochtitlan.

Supervised Meeting Places Were Supported

Within the confines of this tense and disciplined world, people created clear ways for young people to meet and fall in love, with the support of those around them. Training halls, marketplaces, and festivals supervised by elders, evening dances watched by older women, all created small, precious spaces for human connection.

A look passing between two students in the Telpochcalli could mean everything precisely because it had to be brief. Desire lived like a protected ember in a world full of noise.

The Aztec Language Of Love Was Poetry

Courtship unfolded carefully and was encouraged within certain strict limits. The Aztecs did not confess feelings directly. Their love language rested on metaphor and restraint, especially in the flower Songs that survive in the Cantares Mexicanos.

A boy might say he sought a precious flower, and a girl might answer that such a flower must not have its petals bruised. Another fragment speaks of a heart opening its wings but being unable to fly. These lines reveal an emotional intelligence that surprises many people, dignity and longing held together in one breath.

The Highly Regarded Aztec Matchmaker

When it came to marriage, families sought the guidance of a matchmaker, usually an older woman who had spent decades observing everyone in her calpulli.

These neighbourhood groups were close and tightly woven, which meant she had attended their births, celebrated their name-giving rituals, watched their arguments, listened to their laughter, and carried a private archive of who got along with whom. She did not guess. She made informed decisions.

Matchmaking decisions were shaped by the social dynamics within the calpulli, the tight neighbourhood groups where families lived and worked together. Because everyone knew one another well, a matchmaker could draw on years of observed behaviour, family reputation, work habits, temperaments, quarrels, alliances, and past conflicts.

A family with a history of stability or cooperation was seen as a good match, while families that created disorder were avoided. Disharmoney was a threat to the very cosmos.

The calpulli created a setting where nothing was hidden, so marriages were arranged with a realistic understanding of character and compatibility rather than guesswork.

The matchmaker’s role blended experience, spiritual knowledge, and a profound sense of social responsibility.

The matchmaker also consulted the ritual calendar, the tonalpohualli, which assigned personalities and destinies to birth signs. In her eyes, a marriage needed both emotional balance and cosmic harmony. Once she approved the union, preparations began.

Marriage In Aztec Culture Was Popular No Matter the Age

Aztec couples usually married later than expected. Women often married between sixteen and twenty, men between twenty and twenty-five, after proving themselves through labour or military training.

Older marriages were common, too, since widowhood was frequent and companionship mattered. Marriage was a social anchor, a household structure, and a stabilising force in a world that prized order above almost everything.

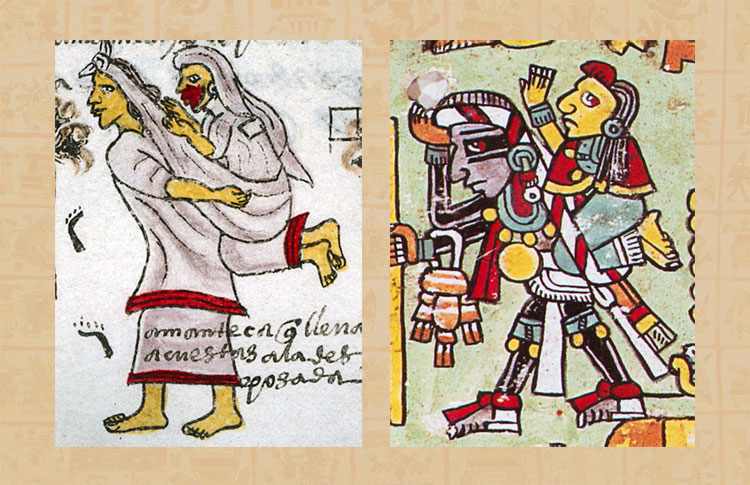

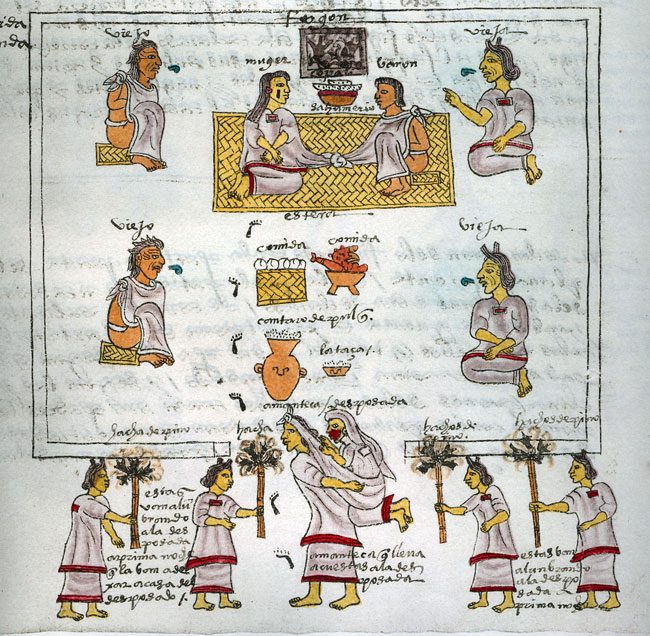

The Aztec Marriage Ceremony

The ceremony itself moved slowly and gracefully. The bride was bathed and dressed with care, and the groom arrived with musicians and relatives. The matchmaker tied the corners of their cloaks together, forming a new household.

Priests burned incense but did not officiate. The true heart of the ceremony belonged to the families and the matchmaker.

Advice was given to the couple. With a focus on patience, cooperation and what daily work was required to build a happy marriage.

Marriage And Pregnancy

The Aztecs understood practical life as well. Herbal contraception existed, particularly through plants like zoapatle, which midwives used to regulate fertility. Zoapatle also induced labour, helped with menses and aborted children.

Certain months were avoided for intimacy, and the calendar itself served as a guide for spacing children. Extended breastfeeding also helped, reducing fertility and creating natural intervals between births.

Fidelity In Aztec Marriage

Fidelity within marriage held enormous weight. A married woman involved in adultery could be executed, and the man with her faced the same risk. Men had more freedom in theory, yet even they were forbidden from approaching a married woman in any way other than in a friendly manner.

Marriages were important because if one of the partners messed up, the sun would fall from the sky, so people did not take such situations lightly.

A Pregnant Woman Was Considered A Warrior

Pregnancy carried its own gravity. A pregnant woman was considered a warrior preparing for battle. If she died in childbirth, she was honoured like a fallen soldier and believed to accompany the sun on its journey. Few cultures gave motherhood such fierce reverence as the Aztec culture.

At times, Aztec life can seem harsh and cruel, but love did thrive in this environment despite it all.

A warrior might return home after battle to share food with his wife, and a woman might sit weaving by lamplight waiting for her love to return.

Roles Within Aztec Marriages

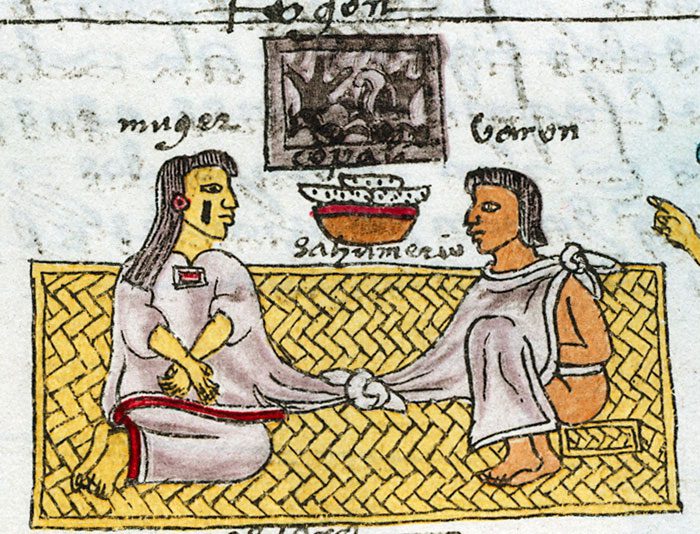

In an Aztec marriage, each partner had clearly defined responsibilities. A husband handled the household’s external duties, such as farming, trading, military service, paying community obligations and taking care of his family.

A wife managed the day-to-day running of the home, including tending the hearth, preparing food, weaving cloth, organising resources, and raising the children. Both partners shared tasks such as teaching values, maintaining the family’s small rituals, and keeping the household steady.

These roles were practical and well understood, and a marriage worked best when each partner carried their part reliably and cooperatively.

Their tenderness was not separate from the hardness of their world; it grew from it. Love became a refuge, a place where people could find peace and nurture, much like today.

This is the texture of Aztec love, a balance of restraint and longing, responsibility and desire. Fierce by day, tender by night. A reminder that even in a civilisation where the sun itself needed human devotion, the human heart still found its way toward warmth.