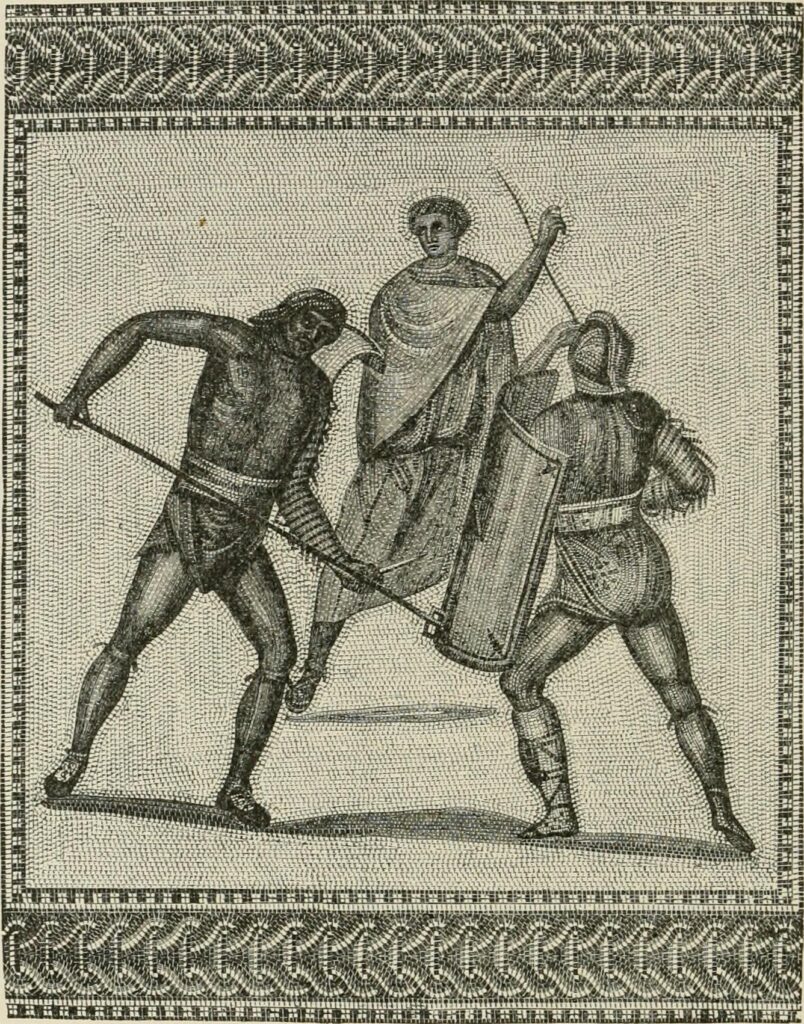

Everyone is aware of the idea of gladiators fighting in the arena for the pleasure of the audience, but what was life like for them before they had to go and put on a spectacle? In fact, what did gladiators do the night before a fight? It’s probably a bit different from what you would expect.

1. They Gorged On A Final Feast (And Everyone Watched)

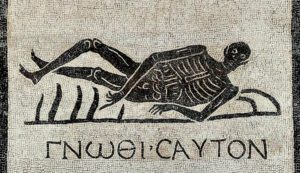

The cena libera, the “free meal”, was a gladiatorial tradition, but calling it “free” was darkly ironic. These men were about to die for public entertainment, and their last meal was part of the show. The feast was extravagant by their standards: barley porridge bulked up with beans and dried fruit, occasional meat, and wine that flowed more freely than usual. Skeletal evidence from gladiator cemeteries shows their normal diet was heavy on plants and grains, as evidenced by the high-strontium signature archaeologists find in their bones.

But here’s the grim bit: it wasn’t private. Spectators could buy tickets to watch them eat. Imagine eating your last meal and having people stare at you like a monkey at the zoo. Gladiators had to perform through that meal too, no matter how they felt.

2. Fans Snuck In To Gawk (And Some Offered More Than Admiration)

Gladiator barracks at night were accessible in ways that would horrify modern security. Fans, and we know they were obsessive from the graffiti found at Pompeii, found ways to get close to their heroes. Women particularly. Graffiti from Pompeii explicitly references gladiators as objects of sexual fascination: “Celadus, the Thracian, makes the girls sigh.” Gladiators were the sex symbols and celebs of their time.

Archaeological evidence from barracks shows that, despite being technically imprisoned, gladiators received visitors. Some women offered themselves to the gladiators, a mixture of morbid fascination, transferred vitality or simply because they were celebrities. The men who gave them what they wanted probably did it for mixed reasons. A small pleasure, a moment in time, or perhaps still playing the game they had to play.

3. They Were Not Allowed to Make Wills (They Were Nothing and Owned Almost Nothing)

Gladiators made a will the night before, but it was rare. The absurdity wasn’t lost on anyone. Gladiators owned nothing; that is why they were there. They’d leave a few coins and a small personal item. It was more of a show than actually worth anything.

The will-making was partly practical but mostly psychological. It was an assertion of personhood in a system designed to strip it away. By making a will, a gladiator briefly became a citizen with property and agency, rather than an instrumentum vocale, a “talking tool,” as Roman law classified slaves. Once again, it was a performance.

4. Veterans Told Them Exactly How Bad It Would Hurt

If you survived your first bout, you joined a grim fraternity. Veteran gladiators didn’t sugarcoat what was coming. The night before, they would focus on the newcomers. Terrifying them with details like how long you’d live after a particular wound was inflicted. How you’d feel if the crowd turned on you. This was to ensure that the new people understood the showmanship of the fight.

It also lowered panic, which promised death. If you could hold it together, you might not be executed if you did live.

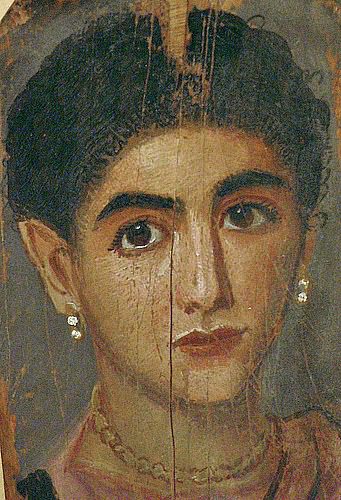

5. Some Prayed To Gods Who’d Already Failed Them

Archaeologists have found that offerings, inscriptions, and prayers took place before games. Some prayed to Hercules, the patron of strength and labour, or to Nemesis, the goddess of revenge and fortune.

The bitter irony: many of these men had already proven their gods didn’t intervene. They’d been captured in war, enslaved, sold. But humans pray anyway. The prayers weren’t necessarily about survival. Sometimes they were about dying well, about courage, about their names being remembered. Prayers can give people inner peace, even gladiators.

6. They Inspected Weapons They Hadn’t Chosen

Gladiators didn’t choose their weapons. Those were assigned based on their fighting style, which itself was determined by their body type and how much their lanista (trainer/owner) had invested in them. But before their battle, they were allowed to handle the actual weapons they’d use.

This inspection was part ritual, part practical. Checking the balance, the edge, looking for imperfections that could mean the difference between a clean kill and a jagged, slow one. Archaeological finds of gladiatorial equipment show these were quality weapons. Rome didn’t stint on the tools of spectacle. Someone had lovingly forged the thing that might open your throat.

7. They Wrote Their Names On Walls (Proof They’d Existed)

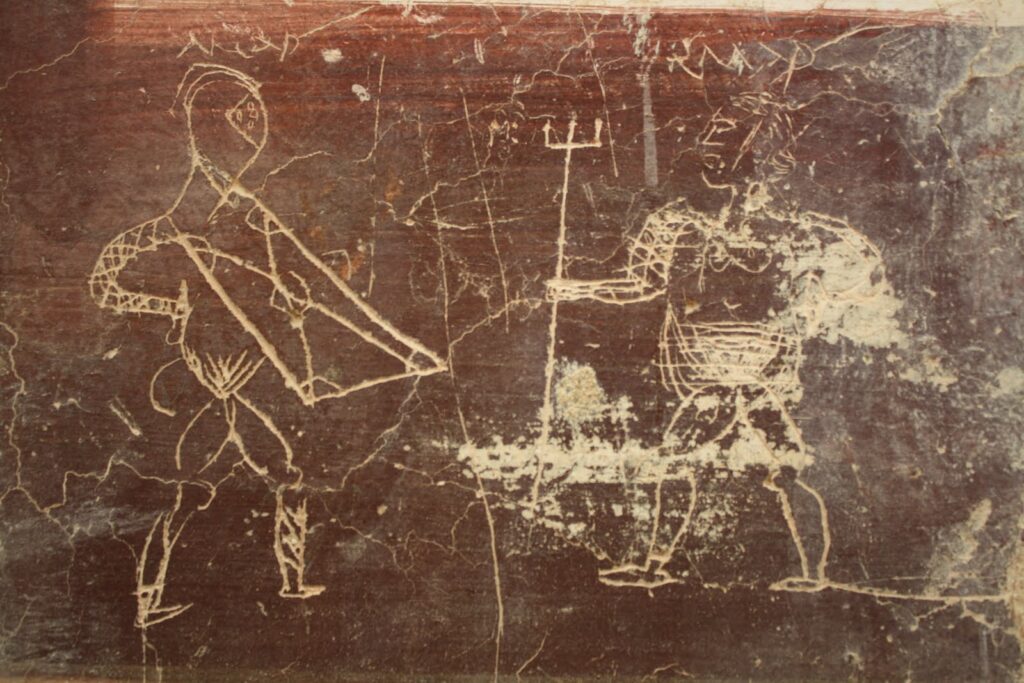

The graffiti at Pompeii’s gladiator barracks is haunting precisely because of its mundanity. Names carved into plaster. Tally marks of victories. “Florus was here.” The night before potentially dying, some men’s impulse was to leave a mark, any mark, that proved they’d lived.

This wasn’t artistic expression; it was existential desperation made physical. In a world where gladiators could be killed and forgotten within hours, their bodies thrown into mass graves, that scratched name in plaster was immortality. It meant they mattered even if for such a short time. Archaeologists can still read some of these names two thousand years later.

8. The Ones Who Knew They Were Doomed Got Drunk

Not everyone faced death with stoic courage, and the sources admit this. Wine flowed more freely before games, and for men who’d drawn particularly bad lots, facing a champion, armed poorly, weak from previous injury, getting obliterated was a rational choice.

The drunk gladiator was probably less entertaining in the arena, moved more slowly, and died messier. But he also felt less. The Romans appreciated spectacle, but they weren’t entirely monstrous. No one stopped a doomed man from numbing himself. A drunk man still died, but he screamed less convincingly. However, while it was allowed at times, some trainers preferred their gladiators to be of sound mind to ensure the gladiator was in perfect condition.

9. Physicians Examined Them (To Ensure They’d Die “Fair”)

Roman games had medical staff, and before major bouts, physicians would examine gladiators. This sounds humane until you understand the purpose: they were checking that the men were healthy enough to die properly. A gladiator who collapsed from illness before being struck robbed the audience.

These physicians, often Greek slaves themselves, understood anatomy better than most ancient doctors because they’d seen so much of it exposed. They’d check reflexes, breathing, and look for fever. For the gladiator being prodded and assessed, it was the ultimate dehumanisation: medical science deployed not to save him but to guarantee he’d die according to required specifications.

The strangest part isn’t that men faced death this way. It’s that the system was designed to make them complicit in their own spectacle.

They ate the feast they were ordered to do. No matter if they felt like it or not. They were, in effect, participating in their own ending and doing what they were told despite the grim ending.

Did they do it to retain dignity? The prayers, the fanfare, the rituals? Or did they do it because there was no other choice? Two thousand years later, we still don’t know the answer.