Hollywood shows crucifixion as a neat tableau of outstretched arms and tidy nails through the palms, but the truth was far more brutal.

Roman execution wasn’t symbolism, it was engineering — a system designed to keep a man alive just long enough to feel every breath turn into a choice between suffocation and agony. One archaeological discovery in Jerusalem, a single bent nail through a young man’s heel, has forced historians to confront how wrong our assumptions have been.

Every breath was a choice: suffocate, or make it worse. Push up on the nails hacked into your feet, feel them grind against the heel bone, raw bone on nail.

Pull up on the nails in your wrists, which will send fresh electrical fire through the median nerve, up both arms, again. Just to exhale. Just to take one breath out.

It’s a hopeless choice, but the instinct of survival is intense.

The Romans had perfected something worse than death. They’d engineered conscious torture that could last for days.

And just so you know, the nail didn’t go through the palms.

That’s Hollywood.

The Archaeological Evidence for Crucifixion

In 1968, construction workers building a house in Givat HaMivtar, northeast Jerusalem, broke through into an ancient tomb. What they found inside would live with them forever.

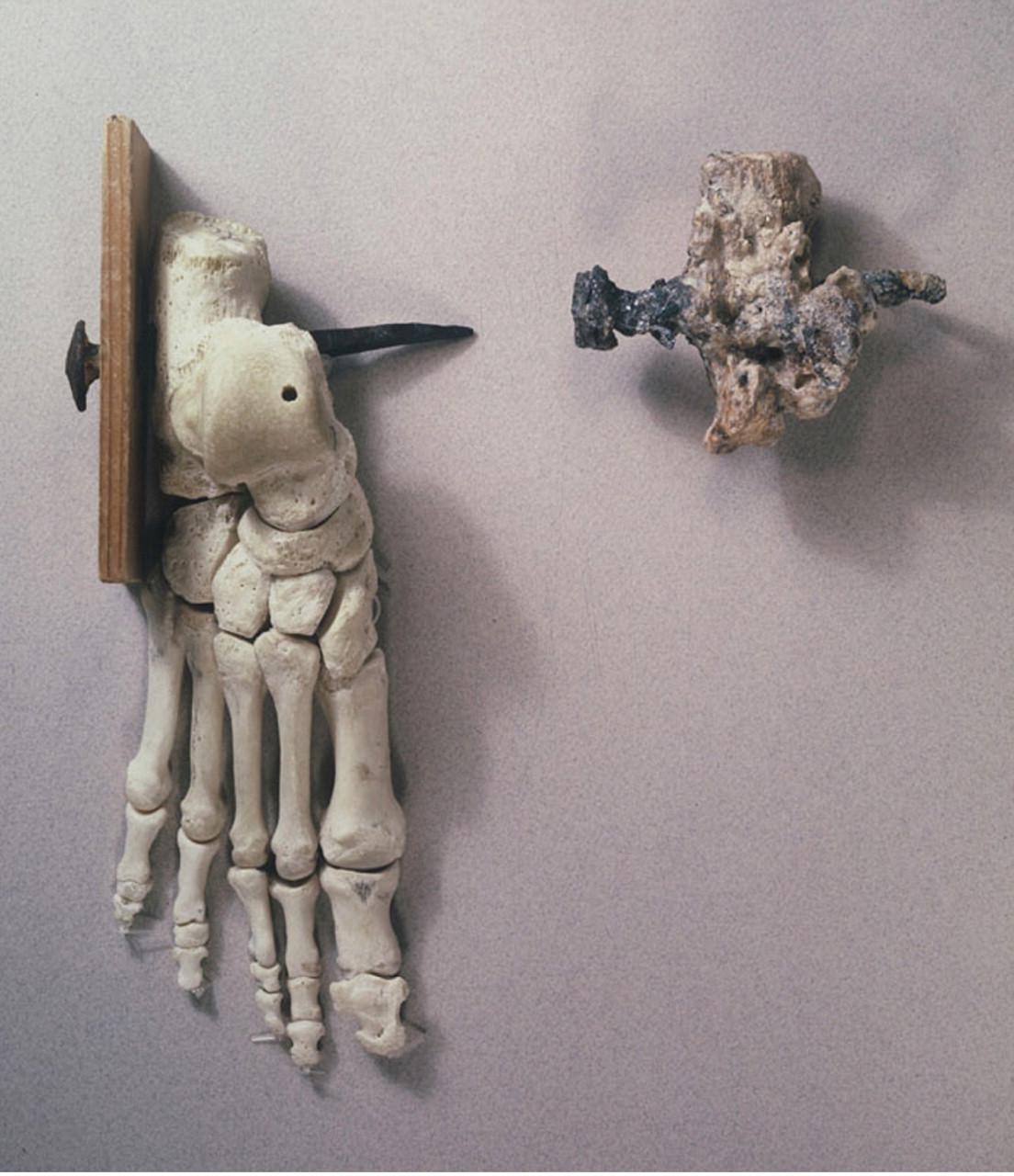

Inside, archaeologists found an ossuary, or bone box, containing the remains of a man named Yehohanan ben Hagkol. He’d been crucified sometime between 7 and 66 CE. He was in his mid-twenties when he died.

They knew he’d been crucified because a 7-inch iron nail was still lodged through his right heel bone. The tip had struck a knot in the olive wood of the cross, bending it and making it impossible to remove. His family had to bury him with the nail still in his body, with fragments of the cross still attached.

This is the only crucifixion victim ever found with the nail in place. The only one. And it rewrites everything.

First: the position. Yehohanan hadn’t hung with his feet together, Christ-like, the way every Renaissance painting shows. His legs had straddled the vertical beam. That alone is different from what you will have expected.

The Mechanics of Death with Crucifixion

Each heel was nailed separately to either side of the upright post. Picture that. A man forced to straddle a wooden beam, a nail driven through each ankle, his full weight grinding down on iron spikes embedded in bone.

Second: the nails in the hands—or rather, the wrists.

Not the palms. Never the palms. Early experiments with cadavers proved what the Romans already knew: nails tear straight through the soft tissue between the metacarpal bones. The hands can’t support a body’s weight. They rip free.

The nails went through the wrists, driven between the radius and ulna bones. And here’s where the horror multiplies: that placement puts the nail directly against—or straight through—the median nerve.

The median nerve is the largest in the hand. Sever it, and you get two things. First: instant, catastrophic pain. Not the dull ache of a wound. Electrical fire. Every slight movement of the body sends fresh shocks of agony radiating up both arms. The pain doesn’t fade. It doesn’t numb. It screams.

Second: the thumb contracts involuntarily into the palm. Medical researchers studying artistic depictions of crucifixion across centuries and cultures noticed something: a characteristic “crucified clench” where the thumb and index finger fail to flex properly. This wasn’t artistic license. This was an observation. The crucified clenched their hands that specific way because the median nerve damage made it anatomically inevitable.

What Really Happened to the Body

Now add the mechanics of breathing.

When you hang with your arms outstretched and your body weight pulling down, your chest cavity fixes in the inhale position. Your intercostal muscles—the muscles between your ribs—lock. You can pull air into your lungs. But you cannot push it out.

To exhale, the victim had to push up on the nails in his feet, scraping his back against the rough wood of the cross, pulling up on the nails in his wrists, sending fresh electrical shocks through the median nerves, flexing his elbows, bearing his full weight on iron spikes driven through heel bones and wrist bones.

Every breath was a choice: suffocate, or climb your own skeleton in screaming agony.

Most crucifixion victims could do this for days. Not hours. Days. The historical record documents people hanging on crosses for three, even four days, before they died.

What Killed Them In The End?

What finally killed them? Not blood loss from the nails—those wounds were relatively minor. The cause of death was multifactorial: hypovolemic shock from dehydration and any prior scourging. Exhaustion asphyxiation, as the muscles required for that terrible push-and-pull simply gave out. Acute heart failure. Sometimes all three in a cascading sequence.

The Romans had engineered a death that was medically, mechanically, psychologically perfect in its cruelty. It was designed to maximise suffering while prolonging consciousness. The victim remained lucid almost to the end, aware of every sensation, every muscle failure, every electrical burst of nerve pain.

And when the Romans wanted to speed things up? They broke the legs. Specifically, they shattered the femurs and tibias with a club. Not to cause pain—though a fractured femur can cause blood loss of 1,000-1,500 millilitres on its own—but to eliminate the victim’s ability to push up for that agonised exhale.

Without the legs to push, asphyxiation followed within minutes.

The word “excruciating” comes from the Latin crucifixio, meaning “to be crucified.” Ex crucis. From the cross. The Romans had to invent a new Latin word because the existing language couldn’t capture that specific quality of pain.

The Final Proof of Roman Cruelty

Yehohanan’s bent nail tells us one more thing: they left the bodies up as warnings. They didn’t carefully remove the dead. They tore them down, ripping the nails through flesh and bone if they had to. Yehohanan’s nail wouldn’t come free, so they simply cut around it, left the iron and wood embedded in his heel, and gave what remains to his family for burial.

Archaeologists keep looking for more crucifixion victims in the ancient world. They don’t find them. Not because crucifixion was rare—thousands upon thousands died this way—but because nails were valuable and reusable. The Romans extracted them. And bone, unlike that single bent nail in that single bent heel, tells no tales.

Dive Into Substack to Learn More About Crucifixion

Crucifixion is one of the most recognised scenes in Western imagination, yet almost everything we think we know about it is wrong. Art softened it, Hollywood romanticised it, and centuries of repetition turned torture into a symbol.

It took one chance discovery in a Jerusalem tomb, a bent nail through a young man’s heel, to drag the truth back into the light. What the Romans engineered was not a quick death, but a prolonged, conscious dismantling of the human body, breath by breath. Read more on Substack about how real crucifixion worked vs Hollywood depictions.