Reader Discretion Advised: This article contains factual accounts of domestic violence and descriptions of physical trauma that some readers may find distressing.

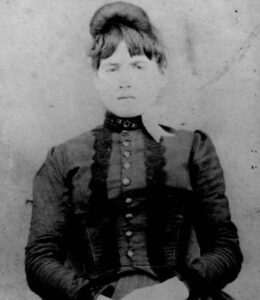

Elva Zona Heaster Shue

We’ve entered the winter season this side of the globe – a dark and dreary season that forms the perfect backdrop for our next true ancient horror story.

Remember, this is a true story.

A Death Too Convenient

The winter air in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, carried that particular cold that seeps into bones, into hearts and sometimes into people’s lives.

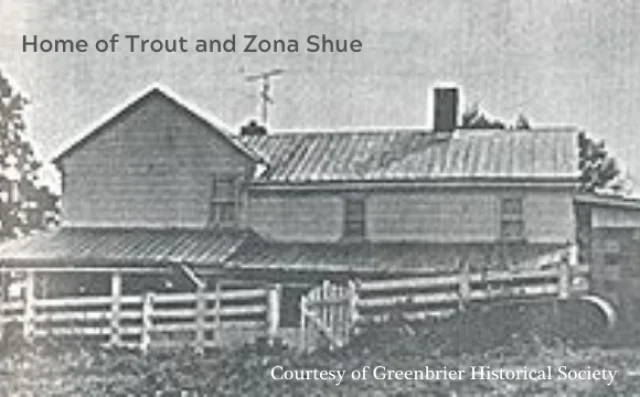

On 23 January 1897, a young boy named Andy Jones trudged through the frost to the Shue house on an errand. He found Elva Zona Heaster Shue, known as Zona, lying at the bottom of the stairs, her body already stiffening in the chill. Her skin was the colour of blue ice, and her eyes stared back at him like two black marbles.

She was dead.

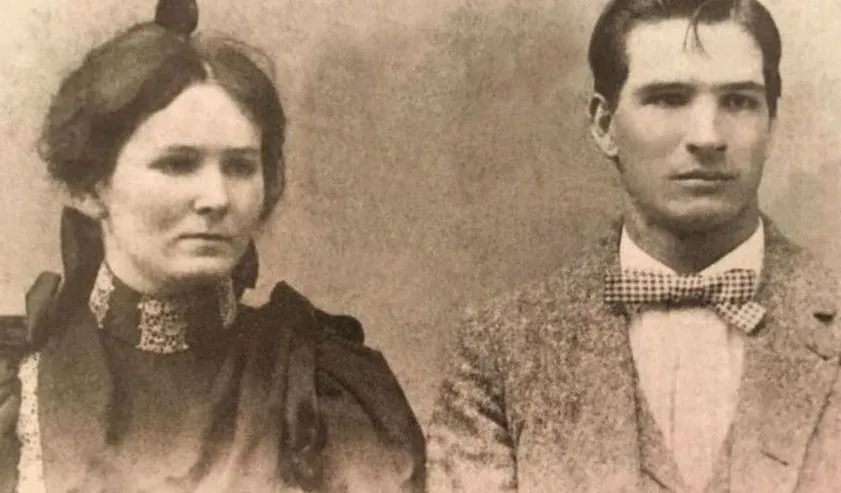

Zona was twenty-three years old. She had been married to Edward Stribbling Trout Shue for precisely three months.

Three months is a particularly short marriage by all accounts, and by all accounts, marriages at three months were still in the honeymoon phase.

Or so one would think.

A Grieving, Loving Husband?

When the doctor arrived, Zona’s husband was already cradling her head against his chest, sobbing hysterically. Of course, he would. She was his wife and, what’s more, his new wife.

Gone.

Just like that.

How can life be so cruel?

In his demented sadness, Edward had dressed her in her Sunday best: a high-necked dress with a stiff collar, fastened so tightly at the throat that it seemed to pinch her neck into a strange position. He had arranged a veil over her face. He rocked her. He wailed. He would not, absolutely would not, let anyone examine her properly.

How could he? She was his precious wife.

The doctor, George W. Knapp, being an understanding sort of fellow, eventually got close enough to check her pulse. Edward Shue’s grief was too overwhelming to push things.

Dr Knapp noted, vaguely, something about “an everlasting faint” and called it heart failure. Or perhaps childbirth. The death certificate would eventually read: “complications from pregnancy.”

How convenient. How terribly, awfully convenient.

The Vigil

At the wake, Edward Shue never left his wife’s side. He kept that veil in place. He had positioned a pillow on one side of her head, a rolled cloth on the other. When mourners tried to pay their respects, he hovered, agitated, protective of the body in a way that made mourners sadder.

What a man, what a husband, so had he loved his wife. That even in death, he was by her side. A little too much by her side, but who are we to judge? We all grieve in different ways, they must have said.

One woman managed to touch the collar. It was rigid. Unnaturally so. When she tried to loosen it, it looked somewhat scrunched. Edward erupted in fury.

He just wanted his wife to look perfect. To look respectable in death as she was in life.

But.

Zona’s mother, Mary Jane Heaster, noticed something else. The sheet beneath her daughter’s head was pink. Not white. Pink with old blood, poorly washed. And when she took that sheet home to clean it, the water in the basin turned red. The sheet itself, impossibly, remained pink.

That night, Mary Jane prayed. She begged God to reveal the truth. To let her daughter speak.

God, or someone, it seems, obliged.

Four Nights of Visitation

For four consecutive nights in late February 1897, something appeared in Mary Jane’s icy bedroom. Not a dream. Not a vision. A presence.

Cold.

Insistent.

Zona.

She manifested fully formed, dressed in the clothes she had been buried in. She moved around the room. She spoke. She told her mother everything.

Edward had killed her. He had flown into a rage because she hadn’t cooked meat for supper. He strangled her with his bare hands, crushing her windpipe, snapping her neck.

Then he had staged the scene at the bottom of the stairs. Then he had dressed her to hide the bruising.

On the fourth night, to prove it, Zona’s ghost turned her head completely around, a full 180 degrees, until it faced backwards. Then she vanished.

Mary Jane woke with the absolute certainty of the already dead.

Exhumation

It took weeks of persistence, but Mary Jane finally convinced the local prosecutor, John Alfred Preston, to investigate.

Edward Shue had been married twice before. Both wives had died under suspicious circumstances. That was reason enough.

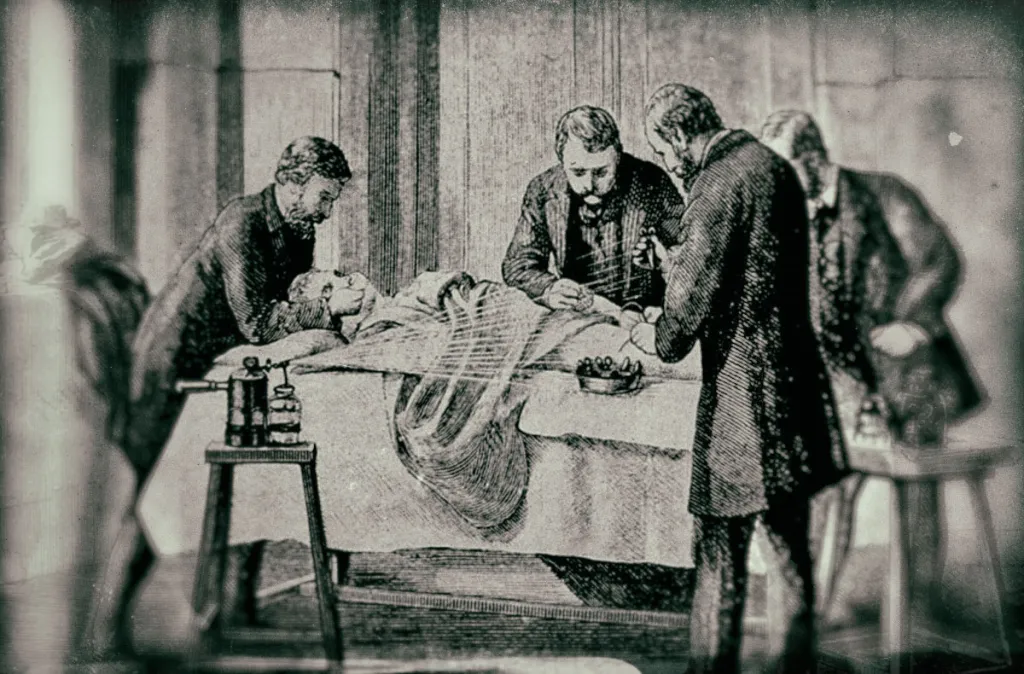

On 22 February 1897, they exhumed Zona’s body.

When they removed the high collar and the carefully arranged clothing, the truth was immediate. Zona’s neck was broken. The windpipe was crushed. Bruises encircled her throat like a necklace. The autopsy report was damning: “the injury to the neck was sufficient to produce death.”

Edward Shue was arrested that same day.

The Trial of the Century (In Greenbrier County, Anyway)

The trial began in June 1897. The prosecution presented the medical evidence. They called witnesses who described Edward’s suspicious behaviour at the wake. They detailed his history of violence against his previous wives.

He was hardly an emotionally wrought widower. He was, in fact, hiding a crime he had committed.

And then, against all legal precedent, they called Mary Jane Heaster to testify for her dead daughter.

She described the four nights of visitation. She recounted every detail her daughter had revealed. The defence tried to discredit her, suggesting she was mad, delusional, and grief-stricken. But Mary Jane was unshakeable. She spoke with the calm authority of someone who had seen the other side and returned with hard proof. It was hard to look away.

The jury deliberated for one hour and ten minutes.

Guilty of murder in the first degree.

What Really Happened?

Edward Shue was sentenced to life in prison. He died there in 1900, maintaining his innocence to the end. The Greenbrier Ghost remains the only known case in American legal history where spectral testimony contributed to a murder conviction.

So what do we make of this? Did her daughter’s vengeful spirit visit Mary Jane, or was she simply a grieving mother whose suspicions found form in dreams she interpreted as divine revelation?

The sceptics will tell you that Mary Jane already suspected Edward. The ghost gave her the courage to demand justice. That the “visitation” was grief and rage that formed a particular narrative.

But the believers will point to the pink sheet that turned the water red. To Mary Jane’s unshakeable testimony. To the fact that she knew details about the murder that were later confirmed by the autopsy. How could she know that?

Some Things We Cannot Explain

The truth often lies in between. Maybe Mary Jane’s subconscious pieced together what her conscious mind denied, allowing her daughter to appear as a conduit for justice.

Or perhaps, just perhaps, some crimes are so violent, so unfinished, that they form a bridge between the living and the dead. And through that bridge, the murdered can speak. Some might argue that Zona’s mother had picked up cues unconsciously that led her to the answer to what had happened. But she was so precise?

The grave in Soule Chapel Methodist Cemetery still stands. Local legend says that on cold January nights, you can sometimes see a figure in a high-necked dress standing near the headstone, her head turned at an impossible angle, refusing to be buried and forgotten.