How a teenage emperor called Elagabalus shattered Rome’s deepest taboos, drowned their hopes and ignited their anger, inspiring stories of murder, decadence, and a banquet of deadly roses that smothered his guests to death.

The Ceiling Is Moving

A single rose petal floats down, brushing the cheek of a senator who cannot move. He was drugged. Above him, the ceiling is shifting. Shadows cross the marble, silent and ominous. The air is thick with perfume, expectation, and fear disguised as anticipation.

In the heart of Rome, beneath chandeliers that drip with gold and ambition, the Emperor watches. He is barely more than a boy, lips curved in a half-smile, eyes cold and hungry. Every guest knows the rules. Flatter him, laugh too loudly, pretend you are not terrified. Try not to notice the guards at every door.

This is the story they told. Thousands of rose petals, released from a false ceiling, drowned senators in beauty. Death by flowers, orchestrated by a teenage emperor who laughed as his guests suffocated.

The story has gone on for hundreds of years, becoming increasingly bizarre as time goes on.

But here is what makes it truly terrifying: we do not know that it actually happened.

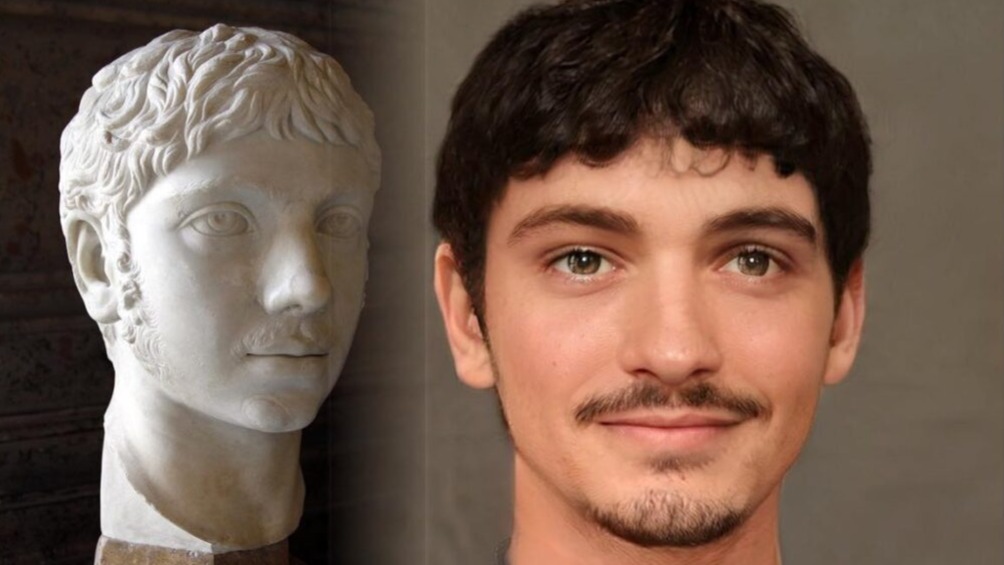

A Boy-Priest Arrives in Purple – Elagabalus

In 218 CE, Rome received its new Emperor. He was fourteen years old, draped in silk robes that shimmered like sunlight, his eyes lined with kohl. His name was Elagabalus, and he came from Emesa in Syria, not as a conqueror, but as a high priest. He had an effervescent air about him, a daredevil’s poise. He was not daunted by anyone. In fact, people of that era found him downright challenging.

He served the sun god Elagabal, a black meteorite housed in a temple thousands of miles from the Forum.

His grandmother, Julia Maesa, orchestrated everything. The previous Emperor, Macrinus, was murdered. The legions in Syria proclaimed this boy-priest the true heir of Caracalla. Rome, exhausted and leaderless, accepted him.

They expected a saviour. What arrived was something else entirely.

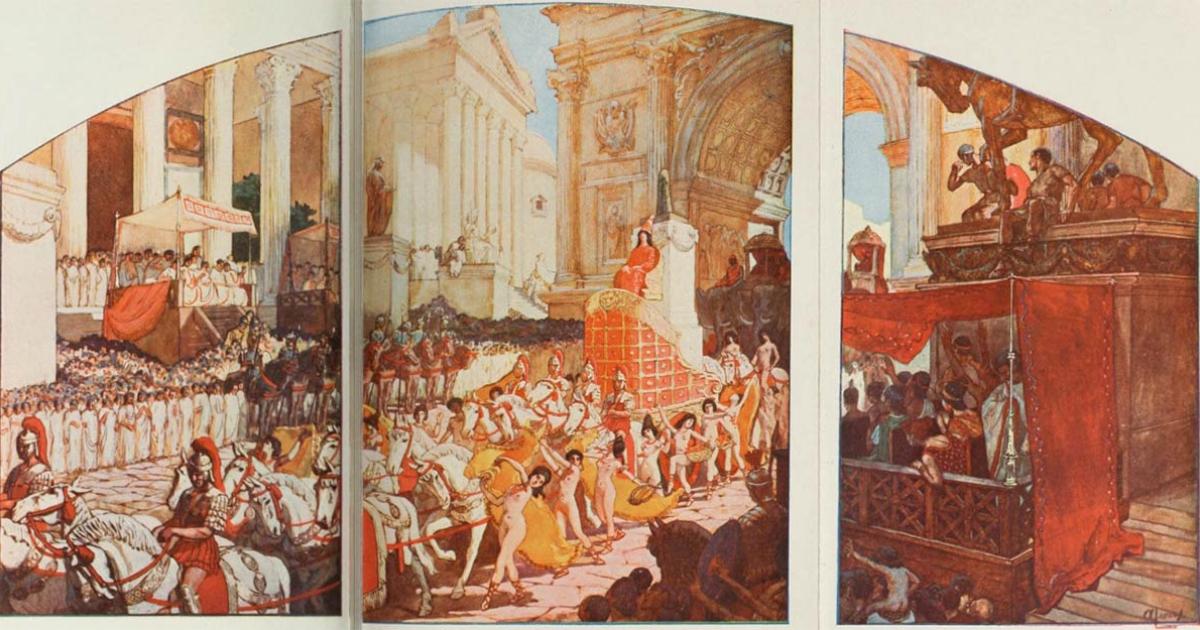

Elagabalus entered Rome not as Emperor alone, but as deity incarnate. He brought his god with him, literally.

The sacred stone was transported to Rome in a golden chariot, and the Emperor walked before it, backwards, never turning his face away from his deity. He built a temple on the Palatine Hill and declared Elagabal supreme over Jupiter himself. A cardinal sin. He did this without thought of anyone’s feelings.

The Senate watched in horror. This was not religion. This was an invasion.

Every Boundary Broken

Rome had rules.

Ancient, unspoken, sacred rules about power, gender, religion, and the body. Elagabalus shattered every single one.

Elagabalus married a Vestal Virgin—priestesses sworn to chastity, their violation punishable by being buried alive. He divorced her and married again. And again. He married men, insisted on being called empress, and, according to sources, asked physicians if they could transform his body into a woman.

He wore women’s clothing through the streets of Rome, painted his face, and adorned himself with jewels.

He elevated a former slave and chariot driver named Hierocles to a position of immense influence, possibly as a husband. He appointed officials based on the size of their genitals, or so the stories claimed. He auctioned government positions to the highest bidder.

He replaced experienced advisers with favourites chosen on whim.

None of this was Roman. All of it was unforgivable.

And so the stories began. If he could break these boundaries, what else was he capable of?

The Banquets of Dread

The invitations were coveted. To dine with the Emperor was to be seen, to matter, to survive another day in the treacherous currents of imperial favour.

But every guest knew: you entered at your own risk.

They said he suffocated senators beneath rose petals—thousands upon thousands, released from a false ceiling, an avalanche of beauty turned lethal. They said he served grotesque banquets where dishes were shaped like human body parts, where the meat was unidentifiable, and where guests ate in silent horror.

They said he released wild animals into dining halls to watch his guests scramble and scream. They said he once served nothing at all—just empty plates and goblets—and he laughed as confusion turned to humiliation.

Real Or Roman Tabloid News?

Every story is recorded in the Historia Augusta, a text written over a century after Elagabalus died. A text historians now recognise as profoundly unreliable—part biography, part fiction, part character assassination. Ancient tabloid journalism dressed as history.

But here is the horror within the horror: it didn’t matter if the stories were true.

Rome believed them. Or needed to. Because a boy who violated every sacred boundary, who mocked Jupiter, who wore silk and called himself empress, who brought a foreign god into the heart of the empire—such a creature was capable of anything. The rose petals became real in the imaginations of men who had already decided what he was.

Perhaps he never killed anyone at a banquet. Perhaps the only murder was slower: the dismantling of tradition, the mockery of everything Rome told itself it stood for.

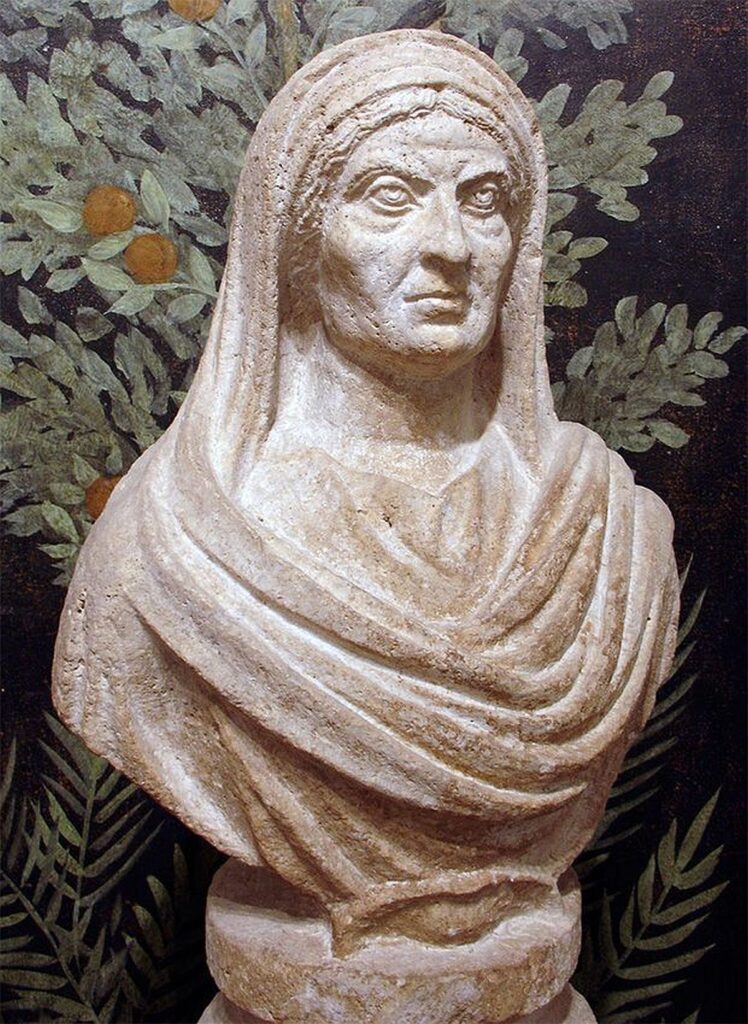

The Women Behind the Son

Elagabalus did not rule alone. He never had.

Behind him stood two women: his grandmother Julia Maesa, the mastermind who had placed him on the throne, and his mother Julia Soaemias, who ruled through him. They attended Senate meetings. They made decisions. They controlled access to the Emperor.

For Rome’s elite, this was intolerable. Women did not wield power. Not openly. Not like this.

But Julia Maesa was no fool. She watched her grandson unravel, watched Rome’s patience fray. And when the time came, she made her choice. She had another grandson: Alexander Severus, twelve years old, quiet, malleable, Roman enough. She began positioning him as heir, then as co-emperor.

Elagabalus noticed. He tried to have Alexander killed.

He failed.

The Corridor

March 11, 222 CE. The Emperor was eighteen years old.

The Praetorian Guard—soldiers sworn to protect him—turned. It happened in a corridor, away from the spectacle and silk. They killed Elagabalus first, then his mother. Both bodies were dragged through the streets, mutilated, and thrown into the Tiber.

His name was erased from monuments. His decrees annulled. His memory officially cursed—damnatio memoriae. Rome wanted to forget he had ever existed.

But they could not stop talking about him.

What Was Real?

Strip away the rose petals, the wild beasts, the grotesque banquets. What remains?

A fourteen-year-old boy, raised as a priest, told he was divine, was handed absolute power over the most powerful empire on earth. A teenager who genuinely challenged Roman gender norms, who married men, and who may have sought bodily transformation in an era that had no concept of it.

A young emperor who elevated his foreign god above Jupiter and expected Rome to bow.

He was not a sadist. He was something Rome had no framework to understand.

And so they made him into a monster. They wrote the stories that would justify his murder, that would explain why an eighteen-year-old and his mother had to be butchered and discarded like refuse. The propaganda did its work so well that seventeen centuries later, we still repeat it. Adding to it, embellishing it.

The absolute horror is not what Elagabalus did. It’s what Rome did to his memory—and how easily we believe the nightmares empires tell about those who refuse to conform. It seems that even the Romans were subject to fake news and propaganda.

The rose petals may be fiction.

The fear was not.