⚠️ Content Warning: This article discusses human remains, ancient surgery, and graphic descriptions of amputation. Intended for mature readers (18+).

Borneo 31,000 years ago

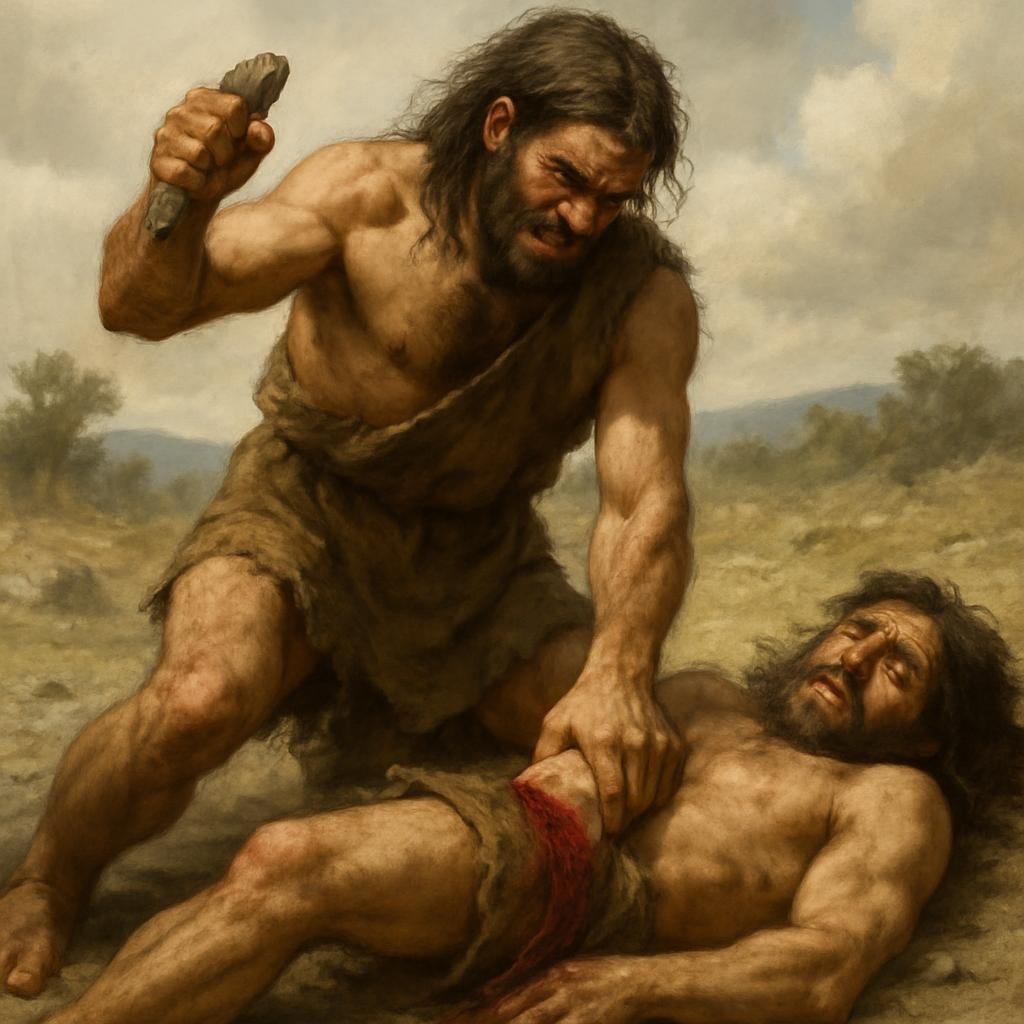

Flames from torches create grotesque, flickering shadows on the cave walls; voices are hushed, and a child is screaming.

The smell of blood and sweat permeates the air, but this is not harm; this is help.

In the darkness of the Borneo jungle, in the Liang Tebo cave, 31,000 years ago, small hands claw at the dirt floor. Others hold the child down, not cruelly, but firmly, because they must. Someone, these people in this time, trust kneels beside them with a stone blade, sharp as obsidian can be made, and begins to cut carefully and precisely.

The Oldest Amputation In History – A Shocking Revelation

There is no countdown, no mask, no promise of oblivion, only the blade, the bone, and a scream echoing off limestone walls. This is the oldest known surgical amputation in history, and incredibly, the child survived. The hardest thing to imagine is surgery without anaesthesia. Yet having a limb removed without it is unthinkable.

Borneo, 31,000 Years Ago: A Cut That Rewrote History

When archaeologists discovered this particular skeleton in 2020, they knew immediately that something was extraordinary. The lower left leg was missing, but not torn away by a predator, not hacked off in combat, not crushed in an accident. The tibia and fibula had been severed cleanly, at an angle, in what appeared to be a single, controlled cut. This was ancient surgery in evidence.

This find, published in Nature, is now recognised as the earliest known surgical amputation in human history (Nature study; Science.org summary; UWA report).

‘This’ Is What Shocked Archaeologists

Despite this being an ancient surgery, the bones had healed completely. Smooth, rounded, sealed. This person lived another six to nine years after losing their leg. Archaeologists gasped in awe. Up until this discovery, we had no idea that people from this time would have had the knowledge to perform such an operation.

Sharpened Stone And Care Was All They Had for Ancient Surgery

In the Palaeolithic era, someone using tools made of sharpened stone performed a successful amputation. They cut through skin that would have bled catastrophically.

They would have cut through a muscle that would have spasmed and torn. Through bone that would have required steady, unrelenting pressure. The child was kept alive through the fever, the delirium, the constant risk that the wound would go bad. After all, they must have previously witnessed individuals suffering from what we now know as an infection.

These Were Not Surgeons, Just Ordinary People

They weren’t surgeons or individuals attending medical schools 31,000 years ago; there were no apprenticeships and no textbooks. But someone in that cave had knowledge passed down through generations, or maybe learned through grim experience. The same person who led rituals, who spoke to spirits, who prepared the dead. Someone accustomed to blood and bone, and matters of life and death.

They Probably Understood It Was A Life or Death Decision

Picture the moment the decision was made. Maybe the unfortunate patient’s limb was shattered beyond repair. The wound had already started to go bad, the flesh hot to the touch, red lines creeping upward, the smell beginning to turn foul. They’d seen this before. They knew what came next: fever, delirium, death.

Someone looked at this child and made a choice: we cut, or you die.

So they cut.

The Horror of Ancient Surgery

No scalpel, no surgeon saw, just a blade of stone, held in a hand that had to stay steady whilst the child thrashed and shrieked. The first incision would have released a sheet of blood.

They would have needed to work quickly, cutting deeper, locating the bone, and then applying pressure with the edge until it began to score through.

Back and forth. The sound alone would have been unbearable. The wet scrape of stone on bone. The snapping of smaller vessels.

And then: through. The leg separated. The stump was left bleeding.

Now came the truly impossible part, keeping the patient alive.

Hot Stones Scorching Embers, Prehistoric Medicine

The bleeding had to be stopped. It was often thought that compression was used, packing the wound with moss or hide. Or, ligatures were used from plant fibres above the cut, strangling the blood vessels closed.

Cauterising The Wound Quickly With Hot Stones

Some archaeologists believe they may have cauterised it, pressing hot stones or embers directly to the raw stump, searing flesh and sealing vessels in an act of agony so profound the patient may have passed out from the pain alone. Which was an immense mercy.

After this event, they knew they had to stop the wound from getting worse.

They already knew that honey kept wounds clean.

Ancient Medicine Still Used Today

They knew that certain leaves, when crushed and applied, could stop the rot from setting in. This wasn’t scientific knowledge; it was hard-won wisdom, learned through trial and terrible error.

Foul Smells And Leaking Warned Them

So they cleaned that wound, day after day. Applied their poultices. Watched for the warning signs: heat spreading from the stump, the smell turning foul, red streaks climbing towards the body. Any of these meant death was coming. These were the fundamental signs of ancient medicine that remain true today in modern medicine and wound control.

The signs never came.

Then came the waiting. The fever. The delirium. But someone stayed with that child. Someone brought water when they were too weak to fetch it, brought food when they couldn’t walk to hunt. Someone changed the dressings. Someone refused to give up. For six to nine years, this person lived, moving differently, adapting, surviving.

Thirty-one thousand years ago, in a cave in Borneo, someone with steady hands and hard-won knowledge did the impossible. And a community refused to let a child die. This underscores the true essence of medicine.

Neolithic France, 4900 BC: The Man Who Lived Without an Arm

The Neolithic French amputation

The burial site at Buthiers-Boulancourt contained the remains of a man in his fifties. His left forearm was missing, not recently, but long ago. The stump was smooth and rounded, indicating that the bone had fully healed. Evidence of his bones showed he had lived for years as an amputee.

The French archaeological institute, INRAP, confirmed that this is the oldest known amputation in Europe (INRAP article).

The Precision Of The Ancient Surgeon in Neolithic France

When researchers examined the bones under magnification, they found something telling. The ulna and radius hadn’t been chopped through in one brutal blow. They’d been cut in a series of controlled slices. Someone had taken their time.

Imagine the fear this man had endured.

Perhaps it was an accident, a fall, a crush injury, a wound that festered. Perhaps you woke one morning to find your forearm swollen, hot to the touch, red lines spreading towards your shoulder. The flesh smells wrong. You know what this means. You’ve seen it before.

The wound has become infected, and once it becomes infected, it spreads. First the arm, then the fever, then death. The word infected was not yet invented, but the signs were there.

A Community Decision To Amputate

The village elders confer. Someone is sent for, the one who knows about these things. Not a surgeon, not a healer with formal training, but someone trusted. It could have been the same person who leads rituals, who speaks to the ancestors, who has seen the inside of bodies before when preparing the dead.

A decision is made.

They lay you down. Others gather, not to watch, but to help. Some will hold you. Others will heat stones in the fire, prepare the tools, bring water, and gather the plants they know help keep wounds from going bad. The same herbs they use on everyday cuts and burns, but this time for something far worse.

You are given something to drink. Fermented grain, perhaps. Something bitter and intense that burns down your throat and makes your head swim. It is not enough.

Imagine The Horror

Someone takes a flint blade, knapped to a vicious edge, and begins.

The first cut is through the skin. You feel it like a line of ice-cold fire. Then deeper, through the fat, into the muscle. The blade has to saw back and forth because there is so much to cut through. Tendons are resistant, slippery and challenging. Blood runs hot over your skin, pools beneath you.

You are screaming. You cannot help it.

They cut down to the bone, and then the real work begins. Flint against bone, scraping, scoring, slowly working through. Your arm is being held at an angle, tight, immobile, whilst someone else cuts. You can hear it. That sound will never leave you. The grinding of stone through your own skeleton.

Then pressure. Enormous pressure. And finally, a crack. The bone gives way.

Your forearm is gone.

You Are Left With A Stump

What’s left is a bleeding stump, and now comes the cauterisation. Stones heated in the fire until they glow are pressed to the wound. The smell of your own flesh burning joins the copper-iron stench of blood. You may have fainted by now. You may have bitten through your own tongue. You may have prayed to gods whose names are lost to us.

But you lived.

Against the wound going bad, against shock, against blood loss and the raw vulnerability of an open wound in a world without sterile bandages, you survived. Someone kept cleaning the stump with water and crushed herbs. Ancient medicine works against sickness. Someone watched for the warning signs, the heat, the smell, the red streaks. Someone refused to let you die.

The Community Cared

You healed. You learned to work with one arm, to adapt, to continue.

When they buried you decades later, they buried you with respect. You were not cast aside. You were not left to die when you became wounded. Your community kept you alive, and you repaid them with years of survival.

The Moche of Peru, AD 100–750: The Will to Walk Again

The Shocking Revelation of Moche prosthetics

By the time of the Moche civilisation in northern Peru, amputation had evolved.

With metal tools, copper and bronze blades, sharper than stone, capable of cleaner cuts, they seemed very well equipped. They had observed enough amputations to develop a technique. Knowledge was being passed down, refined, and improved. And extraordinarily, they had prosthetics.

Artificial Limbs Were In Evidence

Several Moche burials contain individuals with amputated feet and legs. The bones show clean-cut marks, sometimes two or three slices to work through the thickest sections. They show healing. In some cases, they exhibit evidence of artificial limbs.

Wooden feet, padded with textile, strapped to the stump with woven cord. These weren’t symbolic grave goods. They were used. Worn. Functional.

Osteological evidence of these surgeries has been published by archaeologist John Verano and colleagues (Academic study)

Not Only Surgeons But Healers Too

This is what makes the Moche amputations so extraordinary. Someone decided not just to save a life, but to restore it.

The surgery was planned with the prosthetic in mind. The cut had to be at the right level, low enough to remove diseased tissue, high enough to leave a stump that could bear weight. The wound had to heal smoothly and be rounded, not jagged.

A Surgery From Hell?

Picture the surgery. The patient, perhaps a warrior injured in battle, perhaps a farmer with a crushing injury, held down by others offering help. A tourniquet is tied high and tight above the knee, strangling off blood flow. The leg below turns pale, then bluish. Sensation begins to fade, not gone, but muted.

The person performing the cutting, someone with experience, someone who has done this before and seen the patient firsthand, possibly someone who also leads ceremonies and knows the prayers for difficult passages, works quickly.

A copper blade through the skin, creating a neat circular incision. Then, through the muscle, cutting and peeling it back to expose the bone.

Tendons are severed; they snap back with a wet sound. Blood wells up despite the tourniquet.

The Bone Saw: An Ancient Design That Worked

Then the bone saw. Back and forth, steady pressure, the blade biting deeper with each stroke. Bone dust mixes with blood. The leg jerks with each cut, even though the patient is held still. And then, through.

The leg is removed. The tourniquet is released slowly, carefully, watching for the surge of blood. Vessels are tied off with plant-fibre sutures. The muscle is folded over the bone end like a cap. The skin is pulled tight and stitched closed. No antiseptic, no anaesthetic, just common sense and experience.

A Recovery Plan Is Put In Place

The dressings are changed daily, cleaning away the seepage. Someone must bring food, water, and medicinal herbs. This is the first sign of ancient early nursing, the same plants they’ve always used, the knowledge passed down through generations.

Someone must watch for signs the wound is going bad: the heat, the foul smell, the red streaks that mean death is coming. Someone must massage the stump to prevent the muscle from withering.

The Prosthetic Fitting

And when the wound has healed, weeks or months later, someone fits the prosthetic. Something carved specifically for this person, padded for comfort, and adjusted and readjusted until it fits perfectly.

The first time you step on it, it hurts. The pressure on the stump is agonising. But hands reach out to steady you, and voices offer encouragement.

You stand. You take a step. Then another.

You walk again.

The legacy of the Moche extends beyond mere survival to one of restoration. It involves not just saving lives, but also helping people regain their wholeness through mutual care and support.

The Agony They Endured

Here is the part we cannot forget: in every single case, Borneo, France, Peru, there was no general anaesthetic.

Every nerve was alive. Every cut was felt. The patient may have been given alcohol, coca leaves, opium poppy, or other sedative plants.

Shamans may have used rhythmic chanting, trance states, or rituals to distract the mind from the body’s torment. Perhaps these were more powerful than we give credit to.

The Truth About Ancient Amputation

Modern surgeons consider amputation one of the most traumatic procedures, involving intense pain, psychological shock, and profound phantom sensations. The patient’s life changes over time.

The Chilling Truth Of The Bones Stories

Each of these stories points us to unmarked territory.

Borneo, 31,000 years ago: A precise cut with a stone blade shows advanced anatomical knowledge that is beyond human comprehension today.

France, 4900 BC: Multiple careful incisions made with a flint tool reflect surgical techniques that seem impossible at this time, revealing a society that cared for one another even when they were wounded.

Moche Peru, AD 100–750: The use of metal blades, tourniquets, and prosthetics marks the first recorded instances of essential surgeries, aiming not only to save lives but also to restore them.

These are not just medical anomalies; they are powerful examples of human resilience and compassion.

These surgeons, armed with basic tools and immense courage, performed life-saving procedures based on knowledge passed down through generations.

The Aftermath: Living Without

What strikes archaeologists most is not the surgery itself, but what came after.

These people survived because others helped them survive. This shows the strength of human connection and community. As well as an innate intelligence.

The Legacy Written in Bone

When we think of ancient horrors, we imagine sacrifice and plague, warfare and famine. But there is another kind of horror—quieter, more intimate, but no less terrible.

The horror of surgery without mercy. Without anaesthetic. Without the promise of survival. We also see skill in regular humans who care and work out how to help the human body without education.

Further Reading

Further Reading

- Nature – Surgical amputation of a limb 31,000 years ago in Borneo

- Science.org – World’s oldest amputation: Foot removed 31,000 years ago

- University of Western Australia – Earliest known evidence of surgical amputation uncovered in Borneo

- INRAP – A surgical operation of 7,000 years ago: the oldest amputation discovered in France

- John Verano et al. – Foot amputation by the Moche of ancient Peru: osteological evidence and archaeological context

Strong sources & links

- “Surgical amputation of a limb 31,000 years ago in Borneo”, Nature

- This is the key paper for the Borneo case — the “oldest known surgical amputation.” Nature

- PubMed entry for same Borneo article

- Gives abstract, DOI, and reference details. PubMed

- INRAP – “A surgical operation of 7,000 years ago: the oldest amputation discovered in France”

- Published by French archaeology agency, discussing the Neolithic French case at Buthiers-Boulancourt. Inrap

- Academia / Verano et al. — “Foot amputation by the Moche of ancient Peru: osteological evidence and archaeological context”

- This covers the Moche cases, with healing, prosthetics, etc. Academia

- Science / Science.org — “World’s oldest amputation: Foot removed 31,000 years ago”

- A news article summarising the Borneo find, good for accessible linking. Science

- UWA news — “Earliest known evidence of surgical amputation uncovered in Borneo”

- University of Western Australia reporting the find, which is credible and easier for readers. The University of Western Australia