(Historical reconstruction based on documented events)

circa 1450 BCE

What happens when the body is preserved but consciousness remains?

I can’t move.

Not slowly. Not gradually. The paralysis is total and immediate, like someone flipped a switch between my brain and my body. I’m lying on stone. Cold stone. And I’m trapped inside my own skin.

My throat closes.

The chanting starts before I can scream. It fills everything. The chamber. The space between my ribs. My skull. It’s a sound that doesn’t stay in the air; it burrows into bone, travels up my spine, and settles behind my eyes like something living.

I know this chant.

I’ve heard it at every funeral since I was a child. I know what comes next. The priests know what comes next. Everyone knows what comes next except me, and that’s the worst part, that’s the thing that makes my heart start hammering against my ribs, fast, too fast, erratic.

I try to scream.

Nothing comes out. Just a non-gaping silence. My voice is stuck somewhere between my brain and my throat. A whisper. A gasp. The chanting swallows it whole. Before it begins.

A face appears above me. Linen wrapped. Eyes, I can’t see.

“He’s conscious,” she whispers.

“Begin anyway,” a short and concise voice says next.

The undressing happens quickly. Fabric peels away from skin, and the air hits me wrong, too cold, too exposed. I’m shaking. My whole body vibrates with something that isn’t fear anymore, something sharper, something that tastes like copper and salt.

They measure my face. Their hands are steady. Clinical. They move across my forehead, down my cheeks, and I understand what they’re doing. They’re cataloguing me. Before. Before everything changes.

The smell comes next.

Natron. Pure and acrid, and it coats my mouth immediately, fills my sinuses, makes my eyes water so badly I can’t see. I want to cough, but I’m terrified that if I open my mouth, I’ll lose what little control I have left.

The salt smell is inside me now. It’s everywhere.

I think about my wife.

I think about the conversation from months ago that I told myself was hypothetical. Duty. Honour. The preservation of the line. She was there. She didn’t argue. I remember that now with perfect, horrible clarity.

The knife catches light.

Obsidian. Black. Impossibly sharp. And I know. I know exactly what it’s for. Where it’s going. What comes after.

“Give him something,” the younger one says. His voice shakes. “To ease”

“The ritual requires awareness,” the older one cuts him off. “He understands.”

I don’t understand anything.

The blade touches my skin, and everything narrows to that single point of contact. The pain is white. It’s bright. It radiates outward from my abdomen through my entire body like fire spreading through wood.

I’m trying to thrash. I’m trying to move. Nothing works. My body won’t obey. My mouth opens, but the scream gets caught somewhere deep inside, rattling around in my chest like something trapped.

The chanting gets louder.

The melodic voices are terrifying and calming at the same time.

It’s not a chant anymore. It’s a pulse. It’s matching my heartbeat. Or my heartbeat is matching it. I can’t tell the difference anymore. The sound is in my skull, rewiring everything.

Finding this horrifying? Read Next: About the Boy God Rome Destroyed

“The liver.”

He says it like he’s reading from a list. Like this is routine. Like he hasn’t just cut into a living person and reached inside.

They’re moving inside me. I can feel their hands. Their fingers. They’re searching through spaces that should be sealed, should be private, should never be touched from the outside. The violation isn’t just physical. It’s something more profound. Something that goes beyond the body.

The younger priest is breathing hard.

The older one hums. He hums while he works. A little tune. Casual. Obscene in its casualness.

I’m trying to understand why this is happening. Trying to construct some narrative that makes sense. But the only story I have is the one they told me, and it’s crumbling, and all I’m left with is the pain and the knowledge that I’m going to be here for seventy days. Seventy days of this. Of lying in salt. I feel myself desiccate cell by cell. Being aware while the body shuts down.

Unless that’s not what happens.

Unless I’m lying here and they’re lying, and there’s nothing after this but darkness, the slow compression of flesh, and the forgetting.

“How long?” the young one asks.

“Seventy days,” the surgeon says. “He’ll be hard as wood. Perfect for the tomb.”

Seventy days.

The words don’t mean anything anymore. Time has stopped. There’s only now. Only this. Only the terrible awareness that I can feel every single thing they’re doing to me, that I’m conscious of all of it, that there’s no mercy in sight.

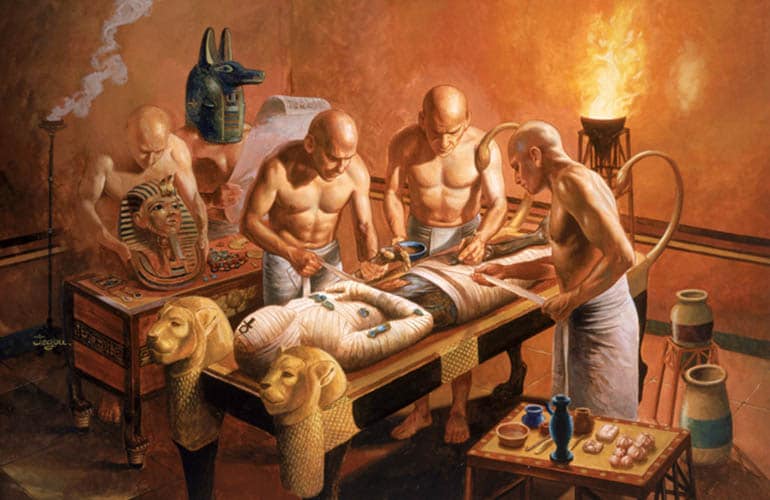

The wrapping starts.

Layer after layer. Tight. Suffocating. My arms pressed against my sides. My legs are bound together. The linen is rough. It smells like resin and something ancient, something that’s been used for this exact purpose a thousand times before. Which it has.

The final layer covers my face.

Darkness. Total. Complete.

The chanting continues through the linen. It sounds different now. Muted but somehow more present. More real. Like it’s coming from inside my own skull instead of from outside.

I’m going to be here for seventy days.

I’m going to be aware of all of it.

And somewhere in that darkness, that’s when the absolute horror starts. Because the worst part isn’t the pain. The worst part is knowing it’s not over. Knowing that this, this moment right now, is just the beginning of something that will last for months. That will change me. That will unmake me completely.

I will last forever.

But I won’t survive this.

Deep Dive: Was Egyptian Mummification Real Horror?

(Deep dive is based on historical and archaeological evidence)

What we’ve just experienced may not be fiction at all.

The Paraschistes: The Surgeon Who Made the First Cut

The ancient Egyptians believed one thing above all else: consciousness persists. After death. Through transformation. Into eternity.

If they were right, then what they did wasn’t cruelty. It was a necessity.

The process of Egyptian mummification took seventy days. We know this from papyri. Clinical descriptions.

Step-by-step instructions written by people who had performed this ritual hundreds of times. The surgeon, the paraschistes, “the ripper”, was a professional. Skilled. Probably trained from childhood for this specific purpose.

He made one incision. Left side of the abdomen. Precise. Then he removed everything: lungs, liver, stomach, intestines. Each organ went into a jar. Each jar was sealed. Each jar was guarded by a god whose job was to protect that organ in the afterlife.

The brain came out through the nose with a bronze hook.

It was discarded. The Egyptians believed the heart was the seat of consciousness. Not the brain. The brain was useless, so they threw it away and let the heart stay, untouched, inside the body where it belonged.

But here’s what the papyri don’t explicitly say: whether any of this happened while the person was still breathing.

Most Egyptologists assume death came first. It’s a reasonable assumption. The merciful one. But certain tomb inscriptions use oddly specific language. Phrases about “awareness through the transition” and “consciousness guided toward eternity” appear in contexts where they seem deliberate. Why describe consciousness at all if the person was already gone?

Evidence of Consciousness: The Horrifying Truth

Modern medicine understands something the ancient world intuited: brain death isn’t instant. It’s a process.

In cases of extreme trauma, massive blood loss, organ failure, and shock, consciousness doesn’t switch off like a light. “It fades in stages, like the lights of a football pitch after a game. One section goes black after another. Sometimes for hours. And during that fading, the person can still hear. Still feel. Still understand what’s happening to them.

Clunk, clunk, clunk, black.

Awake in a body that won’t respond. Trapped. Conscious. Unable to move or scream or stop any of it.

The Egyptians didn’t have the medical terminology. But they had the observation. They knew. Somehow, they knew.

They built an entire civilisation on the assumption that consciousness continues after the body begins to fail. That the soul experiences the dismemberment. That awareness is necessary for the transition into the next world.

They may be right.

Or worse.

Physical Evidence of Struggle in the Tombs

The bodies tell us something. We just don’t want to listen.

Mummies show signs of violence: broken bones. Contracted muscles. Damage patterns that aren’t consistent with natural decay or tomb degradation. The damage is directional. Specific. It looks like someone had been fighting before the paralysis set in. Like the struggle had happened in those final moments before the body shut down completely

Archaeologists have unwrapped thousands. Studied the faces. Some are peaceful. Some are not.

Many mummies have been found with contorted facial expressions. Some from spasms, perhaps, or more, that we don’t know. But what we do know is this: the embalmers took care to close the mouths of the dead. They wrapped the jaws shut. When a mouth remains open after all that care, it tells us something happened, something the embalmers couldn’t fix.

The coffin was sealed from the outside.

The Egyptian tomb inscriptions describe the process in language that shifts between clinical precision and something that reads almost like anguish. The descriptions of consciousness persisting aren’t vague. They’re consistent. They’re specific. They appear in context after context, as if the scribes felt compelled to mention it.

They knew.

Whether through previous generations of observation, through conversations with priests who performed the ritual, through some other source of knowledge entirely, they knew that awareness didn’t end when the first incision was made. They knew it continued through the removal of organs. They knew it lasted through the natron process.

And they did it anyway.

The Impossible Question: Mercy or Torture?

Here’s what keeps researchers awake at night: we can’t prove they were wrong.

We can theorise. We can speculate. We can construct reasonable narratives about consciousness fading, death being instantaneous, and the whole process being merciful. But we can’t prove it.

What if consciousness does persist through Egyptian mummification? What if the ancient Egyptians discovered something we’ve spent millennia trying to forget? What if they built an entire civilisation around controlling it, ritualising it, making it mean something?

Looking at the mummies now, at the expressions frozen in time, at the evidence of struggle preserved in bone and desiccated flesh, we have to ask: were they performing sacred ritual or controlled horror?

The answer is probably both.

But that assumes consciousness actually ended.

That assumes, somewhere in those seventy days, the awareness finally stopped. The mind finally shut down. The person finally ceased to exist.

We can’t know that for sure.

And that’s the absolute horror, not what they did, but that we’ll never know if they were right.