And the two cases that prove it’s not just a phobia

For centuries, people trusted their eyes to tell them when someone had died.

No machines. No monitors. Just a cold hand, a still chest, a room gone quiet. The person looked very ‘dead’. They probably looked dead for a good few hours. Maybe even a few days.

But history kept producing the same nightmare. Bodies that were not bodies. Corpses that were not corpses. People who woke long after everyone had stopped watching.

Most of the records are useless as names were often not used. Even though they are true.

“A woman revived during washing”. “A man who moved on the autopsy table”. “A child who gasped at the wake”. No names, no dates, no way to find out what happened next. If there are dates, they are not well documented.

But two cases cannot be dismissed.

Two women came back with names, witnesses, medical notes and lives that continued afterwards. They are the reason safety coffins came into existence, and it’s clear to see why.

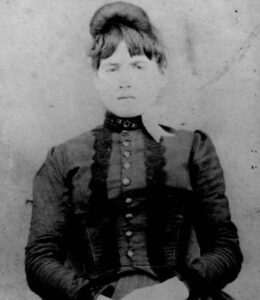

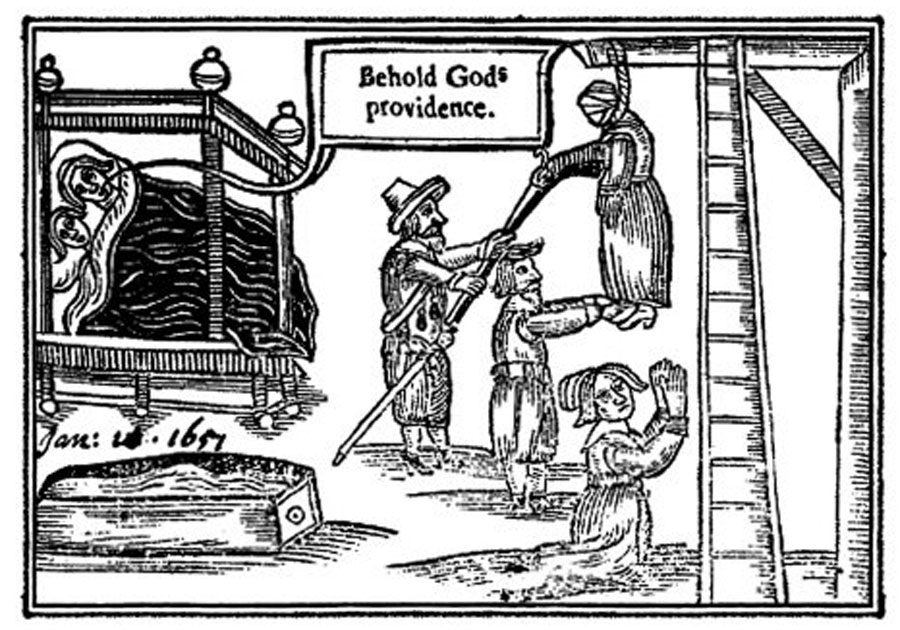

The first was Anne Greene of Oxford, 1650.

She was hanged. Observed and then declared dead. People watched her hang; in fact, the crowd stood by as her body swung.

A good thirty minutes later, she was cut down and taken straight to the anatomy theatre so the surgeons could dissect her.

They placed her on the table.

Laid out the tools.

Prepared to open her chest.

And then it happened.

A tiny breath.

A tremor under the ribs.

Not enough to reassure anyone. Just enough to make every man in the room freeze.

Dr William Petty examined her again. She was warm. Too warm. Not the kind of warmth a dead person should be.

Something Was Wrong

Something was wrong; she seemed alive. Instead of the autopsy, they worked on her for hours as she drifted between worlds. Warm blankets were wrapped around her body, and cordial was forced between her teeth, a warm, medicinal wine to try and shock her heart back into life.

It worked. She slowly clawed her way back to life. She had not died at all, and thankfully, she did not undergo an autopsy.

After being dead, Anne Greene went on to enjoy fifteen years of life. She got married and had children. And later, she would describe the terror of waking up on a cold slab, confused as men stared down at her with blades in their hands.

That is not an easy traumatic experience to live with.

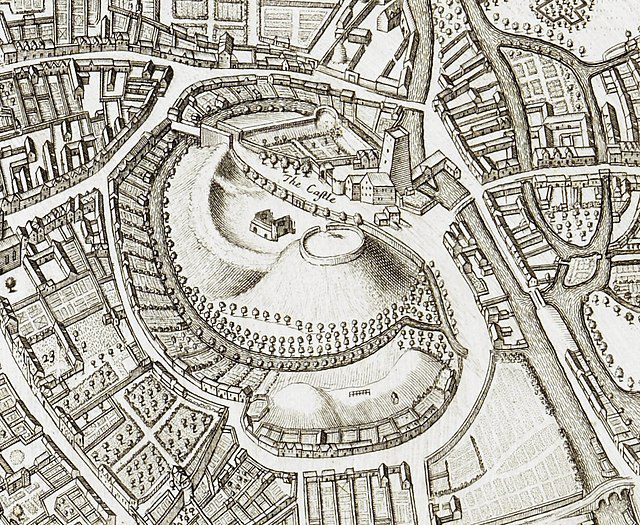

The second case was Margaret Dickson, of Edinburgh, 1724.

Hanged in the Grassmarket.

Tied. Dropped. Pronounced dead.

Her body was nailed into a coffin, as is expected, and loaded onto a cart for burial in Musselburgh.

Halfway along the road, the coffin began to thump.

At first, the men thought it was the cart wheels. Then the noise came again. Louder. When they opened the lid, they found Margaret alive, clawing for air in the tight dark box.

Under Scots law, they could not hang her again. She walked away, remarried and lived for years. A woman who had been dead and then returned to ordinary life as if death had simply missed.

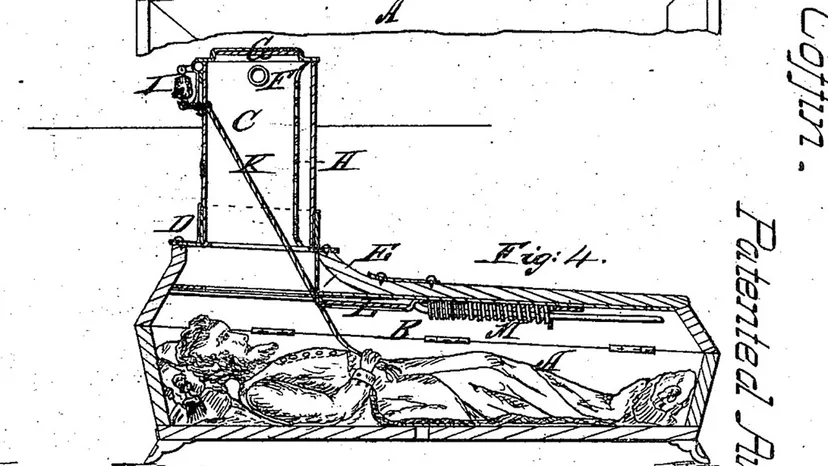

The Safety Coffin

It was cases like Anne Green and Margaret Dickson that created a new kind of terror. If a body could revive hours after the hanging rope or the coffin lid, how many others woke with no chance to escape? That fear built the safety coffin. A pipe for air. A cord tied to the wrist. A small bell above the grave. Crude, desperate inventions designed for one purpose only: to give anyone who woke in the dark a way to call for help even after the soil had closed them in for eternity.

There are stories of people being dug up and scratches being on the lids of coffins. Bodies have moved positions in the coffin. As if this is not terrifying enough.

These two cases are the reason people were terrified. They were not rumours or tavern stories. They were recorded deaths that did not stay dead.

They made every quiet room and every still body suspicious. If Anne and Margaret could wake after the noose, who else had been buried alive without a chance to fight back?

By the late eighteenth century, the fear became policy.

Safety coffins appeared everywhere.

Air tubes funnelled into a coffin for people to breathe.

Ropes tied to the wrist that rang a bell.

Bells above the grave.

Not for ghosts.

Not for folklore.

For people like Anne and Margaret.

For the people who have shifted position in their coffins or tried to scratch their way out.

We might not know their names, but we do know it happened.

People who were alive, unheard and almost taken to the earth while their hearts still struggled on.

When We Are Alone At Night

These are the stories that stay with us. These are the stories that haunt us late at night when it’s deadly quiet. When we often think about life and death and our own mortality.

How many times has it happened? How many people have awoken from a deep sleep, confused about their close quarters? The stifling claustrophobia of a closed coffin buried 6ft underground. No hope to get out, no hope of being rescued. Nothing. Nothing at all.

That is the absolute horror of this story and the knowledge that it is still happening today. Would you prefer a safety coffin when your time comes, or will you take your chances?

Want to Know What We Did With Grief Before Psychology?

Grief is something we all have to contend with, but how did people handle grief before psychology came along to help us? Check out our exclusive post on our Substack that dives into how humans handled this subject.