The documented horror of England’s most infamous execution, where a 35-year-old queen knelt on blood-soaked straw and waited for a blade she never saw

Her husband, the man she loved, King Henry VIII, had her killed so that he could marry his new love, Jane Seymour. This is an enactment of how this might have felt for Anne Boleyn, using factual evidence. Then we dig briefly into what happened to Jane Seymour after their joyous wedding. See these interesting facts on Substack and Kofi. Links below the story.

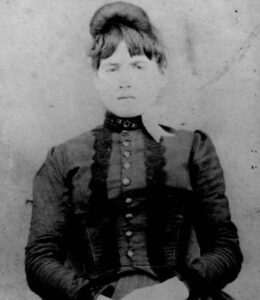

It Begins: The Death of Anne Boleyn

Three Days Before: 16th May 1536

You can hear them building it.

You don’t want to, but how can you escape the loud banging and thuds that echo through the halls? Clack, clack, clack, bang, bang. Relentless, invasive, never-ending.

There is a hollow sickness in the pit of your stomach. This can’t be real. But it is real.

The hammering starts at dawn. Loud. Constant. Relentless. Wood striking wood. Each blow counts down.

One two three

One two three

Each nail driven into timber is a nail in your coffin, except there won’t be a coffin. Not a proper one.

You are Queen of England. You have been for three years. Three years of silk and ceremony, power and authority. Now you’re in the Tower of London, and they’re building the scaffold that will end you forever. The sound never stops. Even at night. Especially at night.

You’re thirty-five years old.

They say the Frenchman, the “Sword of Calais”, will be quick so that you won’t feel a thing. There will be just blackness. A small mercy that you hang onto.

They’re lying.

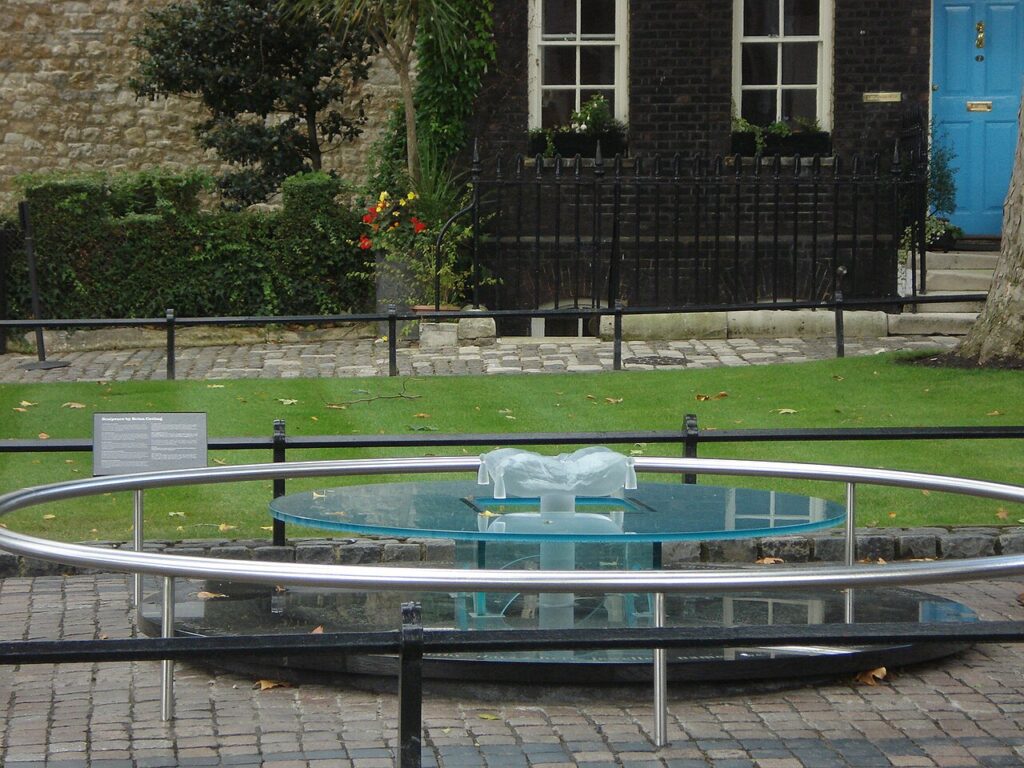

For three days, the hammering continues. Back and forth across Tower Green. Measuring. Sawing. Building. You watch from your window.

Count the planks. Measure the height. Five feet off the ground. Fresh timber. New construction. Built specially for you.

You asked for the swordsman. Paid extra. Twenty-three pounds, ten shillings, nearly a year’s wages for a craftsman. You thought a sword would be faster than an axe. Cleaner. You thought it would hurt less.

You don’t know yet that you’re wrong.

The Night Before: 18th May 1536

You cannot sleep. Your ladies watch you pace the chamber, back and forth, back and forth, like a caged animal. Because that’s what you are now. Caged. Condemned. Already dead, just still breathing.

You laugh sometimes. High. Brittle. Wrong. You joke about your neck, ‘Such a little neck,’ you say, circling it with your hands. Your ladies don’t laugh. They cry instead. Quiet. Stifled. Terrified.

Then you’re weeping too. Sobbing. Shaking. Because tomorrow morning, they’re going to take your head off your body, and there’s nothing you can do to stop it.

You cannot imagine it, you cannot picture it. Yes, wait, you can, and once you see it, you can’t stop seeing it.

The hammering has stopped. The scaffold is finished. Ready. Waiting.

Dawn

You take the sacrament at first light. Kneeling. Praying. Swearing on the body of Christ that you never betrayed Henry. Never. Not once. Not ever.

You mean it. Every word. You swear on your immortal soul, on your daughter’s life, on the damnation of your spirit for all eternity. Either you’re innocent, or you’re willing to burn in Hell forever rather than admit guilt.

The wafer dissolves on your tongue. Bitter. Dry. Final.

Sir William Kingston, the Lieutenant of the Tower, watches you. Writing everything down. Every word. Every oath. Every prayer. He’s keeping records. Official records. Documentation of how a queen dies.

You are a historical event now. Not a person.

The idea that people will read about this in years to come horrifies you. Your blood runs cold.

The Day: 19th May 1536, Eight O’Clock

They come for you.

You’ve been watching the scaffold from your window since the hammering stopped. Counting the planks. Measuring the distance. One hundred and fifty paces from your chamber to that platform.

You dress carefully. Grey damask gown trimmed with fur. Crimson kirtle beneath, the colour of blood. Your hair is pinned tight, every strand controlled, perfect, because you need to be perfect when you die. Your hood is the English gable style. Traditional. Respectable. Queenly.

Your hands shake as you smooth the fabric.

The door flies open.

The Walk

The scaffold is one hundred and fifty paces from your chamber. You count them. One. Two. Three. Your ladies walk behind you. Silent. Weeping. You cannot weep. Not now. Not yet.

The crowd is small. Henry forbade a public execution. Too risky. Too political. Too much chance you’d tell the truth. About two hundred men wait on Tower Green. Courtiers. Officials. Witnesses.

No women. Only your ladies. Only the women who have to be there.

You see the scaffold. Fresh timber. New straw scattered across the platform. The straw isn’t for comfort. It’s to soak up your blood.

You want to be sick, but understand that it’s pointless; you’ll be dead very soon. The vomit in your throat will die with you.

The executioner is already there. French. Expert. Anonymous.

He’s hidden the sword in the straw so you won’t see it and panic. This action is considered a mercy. A kindness. A gift.

You climb the steps. Slowly. Carefully. Gracefully. Because you’re still a queen. Still performing. Still perfect.

Even now.

The Platform

You stand above them all. Five feet higher than the men who condemned you. The morning air is cool on your face. May in England. Spring. Life is bursting everywhere except here. Except now. Except you.

Your Last Speech As Queen: Anne Boleyn

You have to speak. Custom demands it. Your final words. Your last performance.

‘Good Christian people.‘ Your voice is steady. Clear. Projected. You’ve done this before, speaking to crowds, commanding attention. ‘I am come hither to die, for according to the law, and by the law I am judged to die.’

You don’t say you’re innocent. You can’t. Elizabeth needs you to die well. Your nine-year-old daughter’s future depends on this. On you praising the man who’s killing you.

‘I pray God save the King,’ you say.

The words taste like poison. ‘He has always treated me so well.’ The lie burns your throat. ‘He is one of the best princes on the face of the earth.’

The man who ordered your death. The man is already planning his wedding to Jane Seymour. The man you loved. Once. Long ago. Before.

Before this.

You remove your hood. Your ladies move forward. Gentle. Shaking. They tie the blindfold across your eyes. Everything goes dark. You can still hear everything. The breathing. The shuffling. The waiting.

They remove your gown. You’re in your chemise now. Low-necked. Thin. White. You can feel the air on your skin. Cold. Exposed. Vulnerable.

There’s no block. You have to kneel upright. Neck out. Head up. Perfect target.

You kneel.

The Last Moment

Your hands clasp together. Prayer position. The straw prickles your knees through the thin fabric. You can smell it. Hay. Earth. There is something weirdly comforting about the smell.

Your lips move. Words you’ve said a thousand times. ‘To Jesus Christ I commend my soul.’ Over and over. Faster. Desperate. ‘Lord Jesus, receive my soul.’

The executioner is somewhere behind you. You can’t see him. Can’t hear him. The sword is silent. No warning. No countdown.

That’s when he calls out.

‘Bring me the sword!’

Your head turns. Automatic. Instinctive. Human. You turn toward the voice because that’s what people do.

The blade is already moving.

It hits you from the left. Fast. Sharp. Final.

You don’t feel pain. Not exactly. There’s pressure. Impact. Then nothing.

Your head separates from your body. Clean. Single stroke. Professional.

Your body stays kneeling. Still upright. Still in a prayer position. Blood fountains from your neck. Hot. Pumping. Spraying across the fresh straw, turning it dark, wet, red.

Then you fall. Sideways. Heavy. Wrong.

The executioner picks up your head by the hair. Your eyes are still moving. Your lips, too. Working. Trying to speak. Trying to pray. Trying to breathe.

For several seconds, you’re still alive. Still aware.

Still watching.

Then nothing.

After

Your ladies gather your remains. Your body in the grey gown. Your head wrapped in a white cloth. They’re crying. Sobbing. Hysterical now that it’s over.

There’s no coffin ready. Nobody planned for that. They find an elm arrow chest. Old. Rough. Wrong. They place you inside. Body first. Then head. Together but separate. Forever.

You’re buried in the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. No marker. No name. No ceremony. Just a queen in a box under the floor.

Three hundred and forty years later, they dig you up during Victorian restoration work. Your skeleton is small. Slender. Five foot three. Your skull shows the cut. Single blow. Clean through the vertebrae. Left to right.

Precisely as the records describe.

The executioner was an expert after all.

Nineteen days after you die, Henry VIII marries Jane Seymour. White dress. Celebration. Joy.

A joy no longer yours.

You’re already forgotten. Already erased. Already nothing.

Except you’re not nothing. Your daughter becomes Elizabeth I. The greatest queen England ever had. She ruled for forty-five years. Dies in her bed. Old. Powerful. Triumphant.

Your blood. Your defiance. Your refusal to confess.

All of it matters.

All of it wins.

You won.

Sources and Further Reading:

Ives, E. (2004). The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn. Blackwell Publishing.

Weir, A. (2009). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. Jonathan Cape.

Starkey, D. (2003). Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII. Chatto & Windus.

Primary sources: Letters of Eustace Chapuys (Imperial Ambassador), Chronicle of Charles Wriothesley, Tower of London official records held at The National Archives, Kew.

Learn More On Our Substack and Ko-Fi

To get further insights into the story of Anne Boleyn, check out our Substack and Ko-Fi pages.