Showmen, conmen, technicians of torture and men simply looking for work sent hundreds of witches to their deaths. Their tool? The witch prickers needle.

She stands naked to the waist in a stone cell, skin blotched with cold. A man steps forward, a long iron needle glinting in his hand. He says he will find the Devil’s mark, a spot on her body that cannot bleed or feel pain. If he finds it, she dies.

She knows he will find it, somehow.

Across Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, such scenes were familiar. A “Devil’s mark”, a mole, wart, scar, or patch of numb flesh, was believed to be proof of a pact with Satan. The idea appears throughout witch-hunting manuals, including King James VI’s Daemonologie (1597), which gave theological weight to the notion that evil could be physically detected. (read about King James VI’s witch-hunt here)

Where ministers preached, the witch-prickers performed. Travelling from town to town with long pins or custom-made needles, they claimed to identify the mark of the Devil. The reality was much sadder; these men were showmen, torturers, and tradesmen.

The Witch Prickers Work

The witch prickers work was to pierce every inch of an accused person’s skin, sometimes hundreds of times, until a spot failed to bleed. If none appeared, guilt was declared. Torture was technically illegal under Scottish law, but witch-pricking was classed as “examination,” not torment, a bureaucratic evasion that made agony acceptable.

In Scotland, witch-pricking became a paid occupation. During the Great Scottish Witch Hunts of 1649–50 and 1661–62, hundreds of women, and some men, were examined. Local burgh records show payments made to “prickers” for each case investigated. Some were minor officials; others, self-appointed specialists.

John Kincaid And Trick Needles?

One of the most notorious was John Kincaid, active around Tranent and Dalkeith in the mid-seventeenth century. Surviving records show that he was repeatedly hired by towns to identify witches and reimbursed for travel, board, and “services rendered.” Later reports accused him of malpractice, and some accounts suggest he may have been detained when doubts arose about his methods, though no formal record of conviction survives.

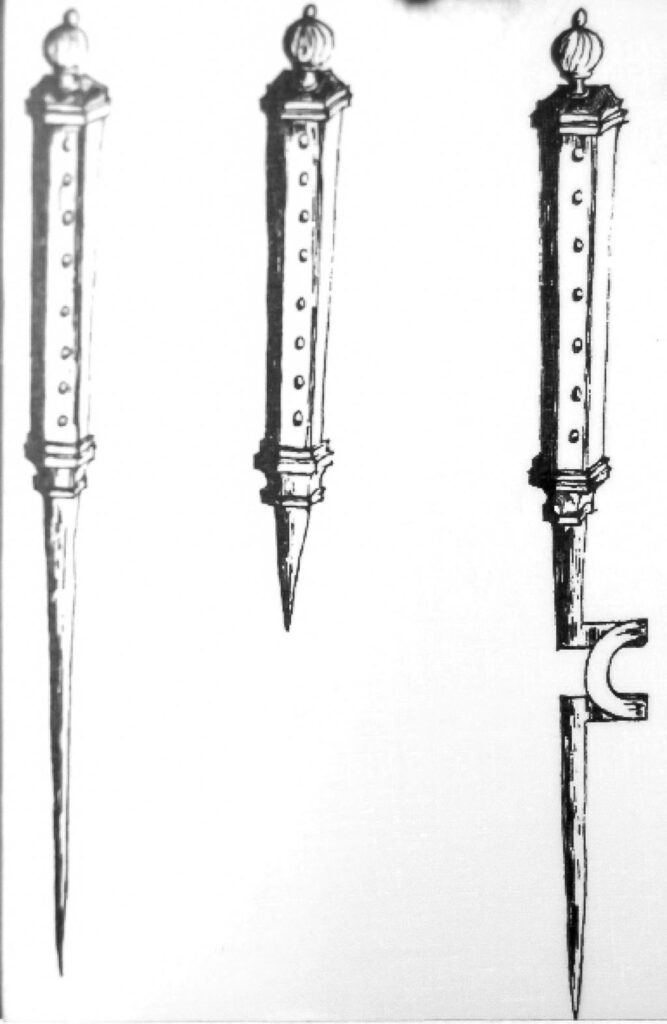

Trick needles were undoubtedly used in the trade. Several retractable examples survive in museum collections, giving the illusion of piercing flesh without breaking the skin. Whether Kincaid himself used such a device is uncertain, but the technique was well known among witch-prickers and may explain how so many “insensible spots” were rather conveniently found.

The Witch Hunt Included Germany and Sweden

The practice was not unique to Scotland. In Germany, the “Hexenmale”, witches’ marks, were sought in mass persecutions such as those at Würzburg and Bamberg in the 1620s. In Sweden’s Dalarna province (1668–1676), interrogators examined women accused of abducting children to the witches’ sabbath at Blåkulla. The marks provided physical “proof” when testimony faltered.

By the early eighteenth century, the trade collapsed under growing scepticism. Physicians began questioning the notion of supernatural blemishes, and magistrates wearied of confessions obtained under duress.

Janet Horne of Dornoch

In 1727, Janet Horne became the last person executed for witchcraft in Scotland, and no pricker attended her trial. Horne was accused of turning her daughter into a pony to ride to the Devil.

Witch-prickers turned fear into income. Each jab of the needle was both performance and transaction, paid for by towns desperate to explain misfortune. They were rewarded for results, not truth. The victims paid with their lives; the prickers were paid in coin.

The “Devil’s mark” faded into folklore, but the idea lingers, that evil can be found if one only probes deeply enough. The witch-pricker’s needle was never just a tool; it was an instrument of certainty sharpened by belief, and belief has always been the sharpest weapon of all.

Continued on Substack

The Devil didn’t need to appear at all, men like John Kincaid did his work for him.

In the follow-up to this story, The Real Horror Was the Man, discover the truth about Scotland’s most notorious witch-pricker, how fear, faith, and profit turned one man’s needle into a weapon of belief.

Read it now on True Ancient Horror Substack

Further Reading

- Enemies of God: The Witch-Hunt in Scotland by Christina Larner

- The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe by Brian P. Levack

- Witchcraft in Early Modern Scotland by Lawrence Normand & Gareth Roberts

- Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries edited by Bengt Ankarloo & Gustav Henningsen