(Historical reconstruction based on actual events)

The rope creaks, leather on wood, weight on fibre.

Below it, the sound is wetter, cartilage tearing, ligaments snapping taut, a scream that starts human and ends somewhere else entirely.

The stone walls drink it in, hold it, give it back in fragments, a haunting echo. The air tastes of rust and piss and something sweetly rotten, like fruit left too long in summer heat.

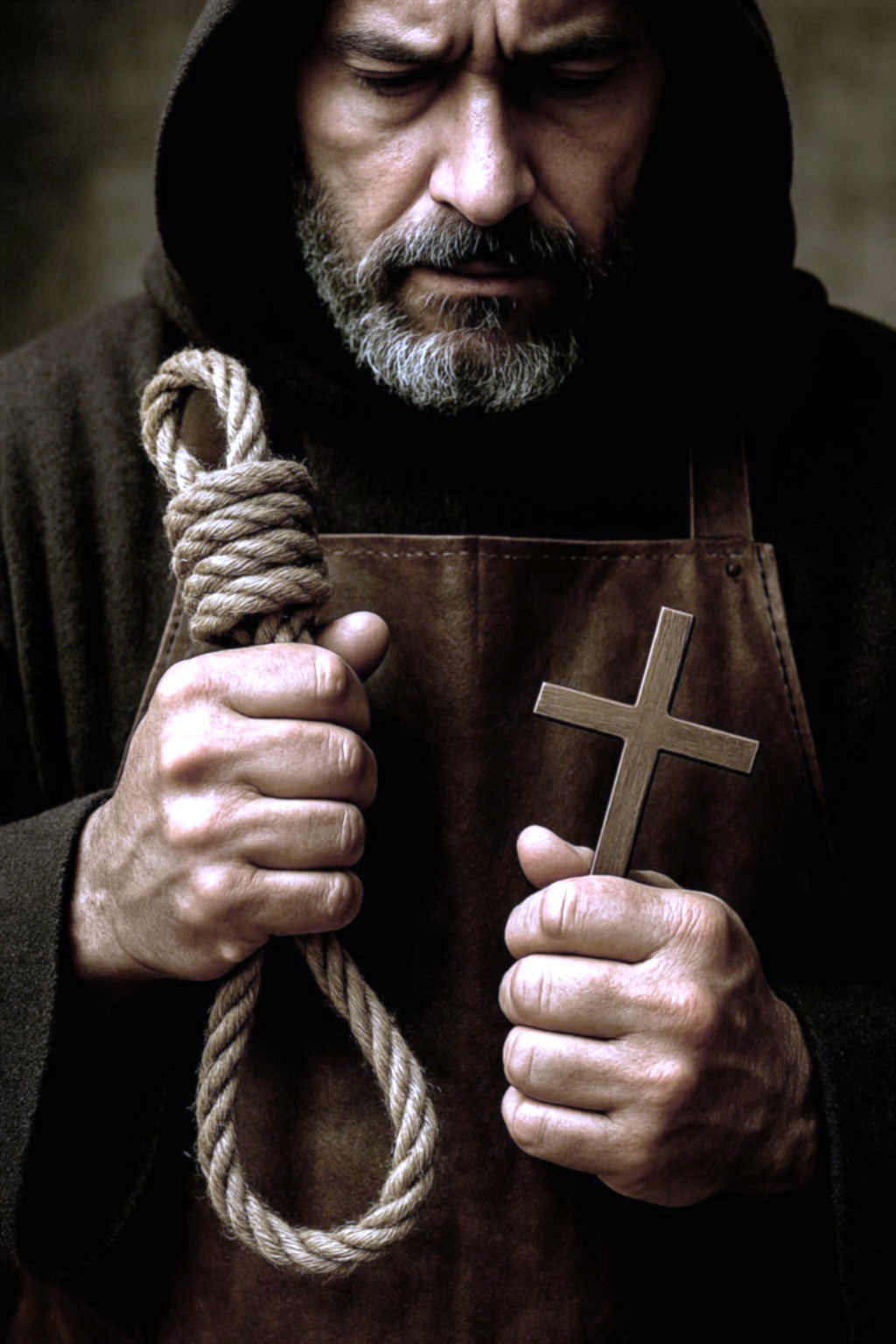

Leather apron tied neatly. Steady, experienced hands tighten the knot. He’s done this to people thousands of times before. He likes what he does.

The chamber is circular. Medieval, of course. Torchlight makes the moisture on the walls look like sweat, like the stones themselves are sick with what they’ve witnessed.

There’s a pulley system bolted to the ceiling, professional and well-maintained, the metal gleaming despite the filth everywhere else. A man hangs from it, wrists bound behind his back, body weight pulling his arms backwards and upward at an angle human shoulders were never meant to achieve. His feet dangle two feet above the floor, twitching.

Satisfied. Brother Thomas of the Holy Inquisition wipes his hands on a cloth with the calm of a butcher between cuts.

This is Strappado

The Interrogation. The shoulders will dislocate in approximately 4 minutes at this body weight, Brother Thomas has learned to calculate it precisely.

Confession usually comes at three minutes, sometimes two if they’re weak or the joints are already damaged. After dislocation, the screaming changes quality. Becomes more animal.

He checks the rope’s tension with steady fingers, evaluating the angle of the suspended arms like a craftsman at work. The man hanging there is either a heretic, a witch, or a Jew who won’t convert; it no longer matters which. What matters is the timing and technique, waiting for the moment when the body breaks and the soul, supposedly, opens.

He wasn’t always like this.

Brother Thomas remembers his first strappado. 1487, late spring, in a chamber much like this one. He’d vomited afterwards, shaking, convinced he’d murdered his immortal soul. The prisoner had been a woman accused of witchcraft. The usual catalogue of flirtations with demons. She’d maintained her innocence for two minutes and forty seconds.

He knew that because he had jotted it down neatly.

Then her shoulders separated with a sound like a chicken wing being pulled from its socket, and she’d confessed to everything.

That night, he went to confession and wept, asking Father Giacomo if God could forgive him for his actions.

“You saved her soul,” Father Giacomo assured him. “Physical pain is temporary; hellfire is eternal. You gave her the chance to confess before she died. You are an instrument of mercy, Brother Thomas.”

In the Name of Mercy – For the Inquisition

The word mercy had been like a drink of wine. Calming, soothing, but also elating.

He believed it then, perhaps because he needed to. The alternative was too horrific to bear.

It did cross his mind from time to time that maybe she had just said yes to end the heinous agony.

That was then. Now it’s different.

Twelve years. Hundreds of bodies. He’s lost count now, they blur together into a catalogue of sounds and angles and the particular way different joints fail under sustained pressure. Men scream differently from women. But agony on all faces looks the same.

By the fifth year, he’d developed rituals. The leather apron is always cleaned. Hands washed before and after, methodically, as a priest washes before Mass. Prayers whispered under his breath during the worst of it – Pater Noster, Ave Maria, the liturgy of the hours marking time as bodies swung and joints popped and heresy was driven out through screaming mouths.

By the tenth year, something had shifted.

He’d begun to see patterns. The way a body in extremis moves like a body in ecstasy, the arch of the spine, the thrown-back head, the loss of speech as suffering transcends language. Saint Teresa was pierced by the angel’s spear. Christ on the cross, arms pulled backwards, shoulders bearing the weight of sin. Faces glorified with agony.

Sometimes, Brother Thomas closes his eyes and sees a bright light. He sees Christ’s radiant face smiling at him.

Mercy

“Confess,” he whispers, his voice trembling with a dangerous rapture. “Confess and be saved.”

The man sobs, trying to speak through the pain that has reduced his words to sounds. Brother Thomas lowers him gently to ease his agony and restore his voice. This is mercy. This is salvation.

“I confess,” the man gasps. “I confess, I confess, please”

Brother Thomas writes it down with steady hands. Another soul saved. Another heretic brought back to the true faith through suffering. He should feel satisfaction, perhaps. Completion of duty.

Instead, he feels a creeping hollowness, an absence where certainty used to live.

Is it True?

Lately, just lately, these past few months, he’s begun to wonder.

If they’d strappado him, would he confess to witchcraft? To heresy? To congress with Satan himself?

If they pulled his shoulders from their sockets and dangled him screaming in the dark, what wouldn’t he admit to?

The thought arrives like a serpent in his mind’s garden. Once invited, it coils there, whispering. All these confessions. All these souls saved. What if they’d all been innocent? What if pain doesn’t purify truth but creates it, manufactures it, forces the mouth to shape whatever words will make the agony stop?

What if he’s been torturing innocents for twelve years while calling it

God’s work?

The man, the reformist, the heretic, is hanging limp now, weeping quietly, shoulders grotesquely displaced. Brother Thomas should call the guards and have him taken to his cell. Should clean the chamber, prepare for the next prisoner scheduled for tomorrow, a woman accused of healing with herbs, probably a midwife whose patient died, probably guilty of nothing but poverty and bad luck.

Brother Thomas watches the rope, the pulley, and the worn groove in the ceiling beam. Unconsciously, he starts to unbuckle his leather apron. The man notices and, with effort, speaks. “Brother?”

“I need to know,” Brother Thomas says quietly. His voice sounds strange to his own ears, distant and dreaming. “I need to understand.”

He binds his wrists with familiar rope and secures the knot behind his back. It has held countless bodies before. Though awkward, he effortlessly ties the knot, having done it so many times that he could do it blindfolded.

Brother Thomas walks to the pulley and feeds the rope through. He tests the mechanism that has served him faithfully for twelve years of God’s work.

“If I pull this,” he says, almost conversational, “my shoulders will dislocate in approximately four minutes. Three if I’m weak. Less if I struggle.”

“Don’t”, the hanging man is saying, but Brother Thomas isn’t listening anymore.

He’s pulling.

The rope goes taut. His feet leave the ground. His full weight transfers to his arms, wrenched backwards behind him, shoulders already screaming in protest as ligaments stretch toward their breaking point.

Oh.

Oh God.

The pain is immediate and nothing like he imagined. Not remotely like he imagined. His mind, which had poeticised suffering into something transcendent, something bearable, whites out under the reality of it. There is no room for thought. No room for prayer. No room for anything except the overwhelming animal need to make it stop, to escape, to confess to anything, everything, any lie that might end this.

He doesn’t last three minutes.

“I confess!” The words tear from his throat before he can stop them, before he can think. “I confess, heresy, witchcraft, Satan, anything, I confess”

But there’s no one to lower the rope. No one to ease the agony and grant the mercy of speech. No one to write down his confession and save his soul.

Just the man, hanging in his own ruin, watching with something like pity as Brother Thomas of the Holy Inquisition discovers what twelve years of his prisoners already knew:

The body betrays the soul. Pain turns nothingness into truth, and agony leads to the loss of humanity, leaving only a desperate need for relief. His shoulders separate at two minutes and forty-seven seconds, and after that, he remembers nothing.

When the guards find them both in the morning, Brother Thomas is unconscious, hanging from the rope like a broken puppet. The other man has somehow managed to drag himself to the door despite his injuries and is slumped against it in agony.

Deep Dive

The strappado, also known as “the pendulum” or “the rope,” was a standard interrogation technique used by the Medieval Inquisition in the 12th and 13th century to the Spanish Inquisition from the late 15th century through the 18th century.

The accused would have their hands bound behind their back and be hoisted by rope, forcing their full body weight onto their shoulder joints. Papal records from 1478-1834 document thousands of interrogations using this torturous method across Italy, Spain, and other Catholic territories.

While individual torturer testimonies are rare, Inquisition trial records reveal that confessions obtained through strappado had a near 100% rate. This statistical impossibility suggests most confessions were false, extracted purely through unbearable pain.

Get More Deep Dives

For insights, deep dives and more, check our Kofi and Substack sites now.