Medieval Europe’s Most Prolific Female Serial Killer Tortured Over 600 Girls Inside Her Castle Walls. This is the true story of Elizabeth Báthory

The Servants Who Survived The Hideous Trauma Described a Countess That Tore Flesh With Her Bare Teeth, Burned Girls Alive for Entertainment, and Kept Basins of Blood Beneath Her Bed. This Horror Show Went On For Years Unchecked.

Finally, the Countess was investigated. A person with a name and status, Count György Thurzó, Palatine of Hungary, demanded that they investigate the castle.

Young Woman Found With Bite Gouges From Human Teeth

The first body was a girl. Drained of blood and discarded like livestock. Her arms bore the tooth marks of human teeth—deep, tearing bites that had ripped away strips of flesh from shoulder to wrist.

The other bodies, pulled from shallow graves in the orchards and stuffed beneath floorboards, showed burns, stab wounds, mutilations so severe the investigators vomited on the spot. Not believing what they were seeing. All the while, the castle and grounds were filled with the familiar stench of death.

Čachtice Castle Was A Human Abattoir

This was December 1610, and inside the stone walls of Čachtice Castle. Countess Elizabeth Báthory had been feeding a sadistic appetite that had turned her castle into a human abattoir.

The servants who survived spoke of silver basins filled with blood. Of screaming that went on for days. Of a noblewoman who had discovered that inflicting agony was better than any pleasure her rank could buy. She was, by all accounts, a sadistic torturer.

The Countess Who Ruled in Blood

Born in 1560 into one of Hungary’s most powerful aristocratic families, Elizabeth Báthory was no ignorant peasant. She was educated and fluent in Latin, Hungarian, German, and Greek.

Not only that.

She managed sprawling estates, socialised with clergy, and hosted the sort of society that required twelve forks at dinner. By all appearances, she was pretty ‘normal’.

When she married Ferenc Nádasdy, a military hero known as the “Black Knight of Hungary”, her status became unassailable. Together, they ruled over lands, serfs, and lives with the absolute authority of the feudal elite.

But Ferenc spent years away at war against the Ottoman Empire. And Elizabeth, left alone in her castles with unchecked power and a growing taste for cruelty, began to experiment.

The Torture Chambers of Čachtice Castle

What started as beatings for minor infractions escalated into ritual sadism. Court testimony, taken from over 300 witnesses during her 1611 trial, describes a catalogue of horrors so detailed they cannot be dismissed as mere propaganda.

Servant Girls And Young Children

Servant girls, some as young as nine years old, were stripped naked and beaten with spiked clubs until their skin split open. Báthory used heated irons, pokers, and metal pincers to burn and tear flesh from their bodies. Needles, hundreds of them, were driven under fingernails, into lips, into the soft tissue of breasts.

Winter offered her more interesting methods of torture. Girls were dragged into the castle courtyard, doused with freezing water, and left to die as ice formed over their skin.

In summer, they were smeared with honey and staked outside for insects to devour them alive. One witness, a woman named Susannah, testified that Báthory once shoved a girl’s hand into a candle flame and held it there, laughing as the flesh blackened and peeled.

Her bloodlust was Astounding

But the Countess did not merely watch. She participated with fervour. Multiple servants swore they had seen her bite chunks of flesh from girls’ faces, shoulders, and arms. She tore at them with her teeth like a predator, chewing and spitting the flesh onto the floor. Derranged, a vampire or possessed? We will never know.

Blood smeared her delicate gowns. It stained the floors so profoundly that even repeated scrubbing could not remove the colour from the stone.

The Myth of the Blood Baths

The image most associated with Báthory, of her bathing in the blood of virgins to preserve her youth and beauty, probably emerged later, embellished by storytellers and historians. This was not proven, but how does one prove that?

No direct testimony from her trial explicitly describes her submerging herself in tubs of blood. Some witnesses testified to seeing basins filled with blood under her bed. She collected this to smudge onto her face to rejuvenate her skin.

The Blood Thirsty Countess Had Supporters

Her accomplices, a wet nurse named Ilona Jó, a manservant called Ficko, and two elderly women known as Dorottya Szentes and Katalin Beneczky, assisted in the killings and disposal of bodies.

They lured peasant girls to the castle with promises of paid work, then locked them in cellars and upper rooms where no one could hear them die. When burial space ran out, corpses were dumped in nearby fields, tossed into rivers, or fed to dogs.

The Reckoning

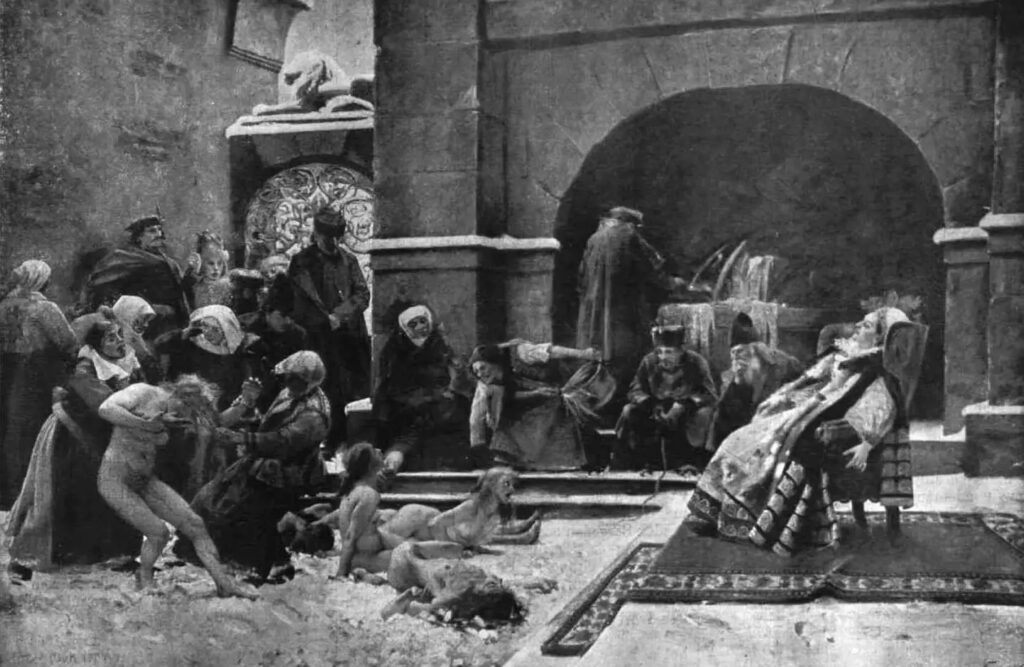

By 1610, the disappearances could no longer be ignored. Even the death of a minor noblewoman’s daughter, someone with a name that mattered, forced the authorities to act. Count György Thurzó, Palatine of Hungary and a cousin of Báthory’s late husband, led a raid on Čachtice Castle on 29th December. What he found confirmed the worst rumours.

One girl lay dead in the main hall, her body still warm. Another lay dying, pierced with holes. In the cellars, they discovered more, some already corpses, others barely alive, their bodies starved and mutilated beyond recognition. Witnesses described the smell as unbearable, a reek of rot that clung to the walls.

Báthory’s four accomplices were arrested, tried, and executed with theatrical brutality. Ilona Jó and Dorottya Szentes had their fingers torn out with red-hot pincers before being burned alive. Ficko was beheaded, then burned. Katalin, deemed less culpable, was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Elizabeth Báthory Never Stood Trial

Elizabeth Báthory herself never stood trial. Her aristocratic blood granted her immunity from public prosecution, an execution would have been an embarrassment to the crown and to her still-powerful family.

Instead, Thurzó ordered her walled up inside her own castle. Masons bricked over the windows and doors of her chambers, leaving only a narrow slot for food and air. There, in suffocating darkness, she lived for nearly four years. On 21st August 1614, she was found dead, face down on the floor.

What the Evidence Reveals

The trial records, housed in Hungarian national archives, document accusations that Báthory murdered as many as 650 young women, though historians generally consider 30 to 100 deaths as reliably evidenced.

Not all poverty-stricken peasants could be accounted for.

Even at the lower estimate, she remains one of the most prolific female serial killers in history, and the deadliest woman.

Scholars Try To Save Her

Some modern scholars argue that Báthory was a victim of a political conspiracy, her crimes exaggerated to justify seizing her lands and wealth. Her arrest indeed came at a convenient time for King Matthias II, who owed her vast sums of money.

Yet the sheer volume and consistency of witness testimony, from servants, villagers, clergy, and even lesser nobles, makes wholesale fabrication unlikely.

The Bodies Were Real: The Testimonies Chilling

The trial records describe injuries in clinical, horrifying detail. The bodies were real. The survivors bore scars.

Feminist historians have rightly noted the misogyny inherent in her legend: the vampiric seductress, the vain beauty bathing in blood. These are archetypal fears of female power and sexuality, projected onto a woman whose crimes were monstrous enough without embellishment.

But to dismiss her guilt entirely requires ignoring the voices of the women who lived through her cruelty, the witnesses who had nothing to gain and everything to fear by speaking.

The Castle That Remembers

Čachtice Castle, located in present-day Čachtice, Slovakia, now stands in ruins, its towers crumbled, its halls open to the sky. The stench of death long faded, but the story of terror never will.

Further Reading and Sources

The surviving trial records and witness testimonies from 1611 are held at the Hungarian National Archives in Budapest, alongside Count György Thurzó’s letters from 1610–1611 describing the investigation.

Among modern accounts, Raymond T. McNally’s Dracula Was a Woman (1983) is still widely cited, though it reflects the Gothic mood of its time. Tony Thorne’s Countess Dracula (1997) is more measured, while Kimberly L. Craft’s Infamous Lady (2009) offers translated testimony and a factual overview. Valentine Penrose’s The Bloody Countess (1970) remains the most poetic, though not always reliable.

For recent academic work, see László Nagy’s “A Historical Re-evaluation of the Báthory Case” (Hungarian Historical Review, 2014) and Gabriella Palló’s “Torture, Testimony and Truth” (Social History, 2018). Both approach the legend with restraint and a critical eye.

The ruins of Čachtice Castle in western Slovakia can still be visited. No formal excavation of the supposed torture sites has been carried out. Still, nineteenth-century renovation records mention the discovery of human remains, reminders that the legend is rooted in something disturbingly real.

Further Reading

For readers interested in exploring the Countess Báthory legend in greater depth, two books stand out.

Kimberly L. Craft, Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory (CreateSpace, 2009).

A detailed and carefully researched study that includes translated excerpts from the original trial records. Craft takes a measured approach, separating rumour from evidence and giving the reader a sense of the political and social world that shaped the legend.

Charles River Editors, Countess Elizabeth Báthory: The Life and Legacy of History’s Most Prolific Female Serial Killer (2015).

A concise introduction that offers a broad overview of Báthory’s life, the accusations brought against her, and the myths that continue to surround her. It is less academic but practical for orientation.

Help Us Keep History Alive

If you love what we do, then you can help support our research by visiting our Ko-Fi page.