Inca Empire, Peru, AD 1400–1500

No anaesthetic. No antibiotics. And it bloody worked. Inca medicine was a marvel.

They survived having their skulls scraped open. Not once. Not twice. Some endured it several times.

In the burial caves around Cuzco, Peru, the ancient capital of the Inca Empire, more than 800 skulls tell a story that shouldn’t be possible.

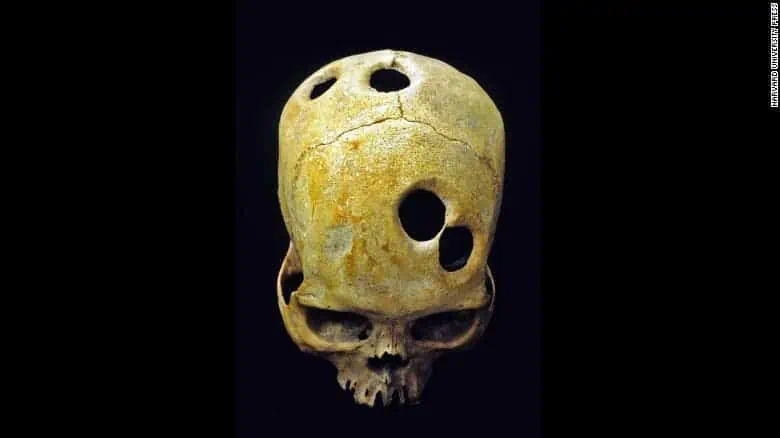

Holes in human heads that were made on purpose whilst they were alive.

These are deliberate, surgical holes carved into living bone whilst the patient was conscious, held between the surgeon’s knees, watching a curved bronze blade descend towards their face.

The tool was called a tumi. A ceremonial knife with a semi-circular blade, sometimes copper, sometimes obsidian, was used in earlier centuries. The surgeon would score an outline on the skull, scraping, scraping, scraping, slowly abrading through layers of bone up to 7 millimetres thick. No drill. Just the rhythmic rasp of metal on skull.

Imagine the feeling, imagine the noise burrowing into your brain.

Paul Broca Recreates the Technique

Paul Broca attempted to recreate the technique in 1867 on cadavers using a glass scraper. An adult skull took him 50 minutes of continuous scraping.

Between 1400 and 1500 AD, at the height of Inca power, survival rates reached 75–83%. Some regions saw success rates as high as 91%. Compare that to the American Civil War, three centuries later, when 46–56% of soldiers died after similar cranial surgery.

But Why Did the Incas Use Trepanning?

It is suggested that it was to relieve brain injury or head injuries from warfare. When the brain swells after a blow to the head, pressure builds inside the rigid skull with nowhere to go.

The surgeons worked out that cutting a hole gave the brain room to swell outward, drained blood clots, and removed shattered bone fragments pressing into tissue. It was emergency decompression, the same principle modern neurosurgeons use today. Very advanced and clever for that period.

The Peruvian highlands were brutal. Warfare was constant. Weapons were sling stones and star-headed clubs designed to shatter skulls. At burial sites in Cuzco, Chokepukio, and Qotakalli, nearly every trepanned skull shows trauma, usually on the left front, exactly where a right-handed opponent would strike. The surgeons learned to avoid areas where cutting would sever blood vessels or pierce the dura mater, the membrane encasing the brain. Pop the dura and your patient is in big trouble.

One skull discovered near Cuzco bears five perfectly circular holes, each surrounded by healed bone. Another has seven. The holes are uniform, roughly 2 to 7 centimetres in diameter, suggesting a standardised technique. These were repeat procedures; each one survived long enough for bone to regrow its distinctive scalloped healing pattern.

Now The Interesting Bit About Inca Medicine

We don’t know what they used for pain relief. Possibly coca leaves. Possibly chicha, fermented maize beer. Possibly nothing. They understood infection control better than future European surgeons.

They likely worked outdoors to reduce contamination and may have used balsam or saponin-containing plants as natural antiseptics. By 1532, when the Spanish conquistadors arrived, trepanation had been refined over two centuries.

At one Cuzco site, 21 out of 59 skulls, over a third, had undergone the procedure. Some were fitted with gold cranioplasty plates covering the holes.

The practice disappeared when the Spanish introduced swords and pikes, as piercing organs became preferable to bashing skulls. This knowledge faded with the last Inca surgeons.

Today, the skulls are housed at the Peruvian National Museum of Anthropology, the Museo Inka in Cuzco, and the Smithsonian. They stand as silent witnesses to remarkable patients who endured the scraping of bronze against bone, returned for additional procedures, and lived on for decades afterwards.

Help Us Keep History Alive

If you like what we do, then consider supporting us on Ko-Fi.