Old St Paul’s Churchyard, London — 3 May 1606

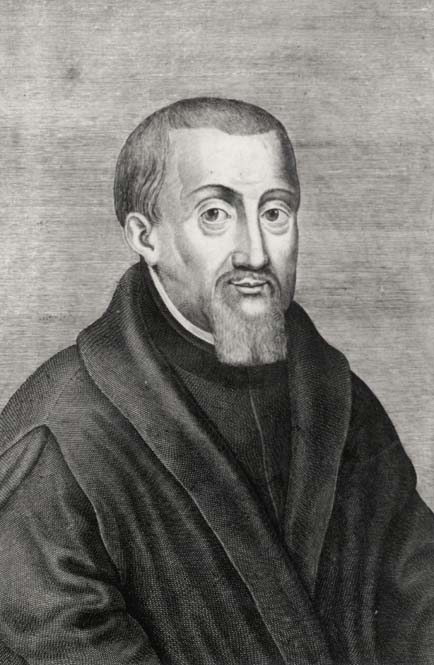

The Execution Of The Priest Henry Garnet

They gathered long before dawn to see Henry Garnet

The crowd. Ready, willing, and excited.

Thousands of them, packed shoulder to shoulder in Old St Paul’s Churchyard, breath misting in the cold spring air. Public executions drew crowds like nothing else, a day’s entertainment, a chance to see justice done, or simply an escape from the drudgery of ordinary life. This one was special: a Jesuit priest, accused of treason for his silence about the Gunpowder Plot.

Henry Garnet, The Priest: A Man Of His Word

Henry Garnet climbed the scaffold just after seven. Fifty-one years old. Jesuit. Teacher. Said to play the lute beautifully, though no one here had heard him. For months, he’d been kept in the Tower, and it showed, his face was grey, his hands steady only because he clasped them together.

The charge was treason. Garnet had known about the Gunpowder Plot.

Known, and said nothing.

Except that wasn’t quite how it went down

The Catholic Sacrament

A man had confessed it to him, under the seal and safety of the confessional. To repeat it would have damned his soul and destroyed the one sacrament that still bound England’s hidden Catholics to their God. Garnet had tried, carefully, vaguely, to discourage the plot without breaking the seal.

It hadn’t worked. And now here he was, rope waiting, crowd baying, the morning light cold and flat on the stones.

He spoke briefly. His voice was quiet. Someone near the back shouted for him to speak up. He said he had offended no man, save in honouring the confidence of confession. A few people booed. Most just watched. They wanted the drop.

The Hanging

The noose went over his neck. The audience held their breath. Garnet crossed himself. He asked for forgiveness for the people who killed him and for any offence he had caused. The executioner kicked the support away.

The drop was eighteen inches. Not enough.

His body jerked, legs flailing. His hands flew to the rope at his throat, instinct, not defiance, and for a few seconds he scrabbled at it, fingernails scraping hemp. His mouth opened. No sound came out, just a wet clicking from somewhere deep in his throat. His feet drummed against the air. A child in the crowd started crying.

Thirty seconds. Forty. Garnet’s face darkened, eyes bulging, tongue pressing forward. A man next to the scaffold looked away. Another stared, transfixed. Garnet’s movements slowed. His hands dropped. His body swung, turning slightly in the wind.

But his chest still rose.

Fell.

Rose again.

The executioner waited. Protocol demanded the prisoner hang until “almost dead.” Almost. That was the point. What came next required a beating heart.

When they cut him down, Garnet’s eyes opened. He gasped, once, twice, a thin, rattling sound like a gate hinge. Someone in the crowd vomited.

The Drawing

They laid him on the block while he was still breathing.

The executioner slit him from groin to sternum. Garnet’s body convulsed. His mouth shaped a word, “Jesu“, and then his jaw went slack. But his heart still beat. You could see it. Thudding against the opened cavity of his chest, dark and slick, pumping blood onto the scaffold in thick, rhythmic pulses.

The executioner reached in. His hand shook. He had done this before, dozens of times, but something about the way Garnet had looked at him, calm and forgiving, had lodged behind his ribs. He grasped the heart, slippery and hot, and pulled.

It tore free with a sound like a wet cloth ripping.

He held it aloft. “Behold the heart of a traitor!”

The crowd said nothing. A woman near the front covered her mouth. A man who had cheered earlier turned and pushed his way out, elbows sharp, face white.

Garnet had not plotted. He had not conspired. He had refused to betray a man’s confession. And for that, they had pulled his heart from his chest while it was still beating.

A traitor’s heart.

The Quartering

The rest was mechanical. Butchery. Four pieces, one for each gate of the city, a warning to anyone who thought silence was loyalty. By the time it was done, the crowd had thinned. Those who remained were silent and pale.

That night, the executioner got drunk and couldn’t stop shaking.

The Sign

Three days later, a woman scrubbing the scaffold noticed something in the wood. A face. Bearded. Eyes closed, mouth soft. It hadn’t been there before.

She called others. Some said it was a trick of the grain. Others swore it was Garnet, burned into the planks by blood or fire or something worse. The authorities ordered the boards scrubbed, planed, and burned. But the story had already spread.

Garnet’s face. Watching. Waiting. A man who wouldn’t break a vow, even as they broke his body.

Some said it was superstition. Others kept their distance from St Paul’s after dark. Perhaps it was a guilty conscience?

And in quiet rooms across London, Catholics whispered prayers to a dead priest and asked themselves: what is faith, if it’s not worth dying for?

Historical Note: Henry Garnet (1555–1606) was executed at St Paul’s Churchyard, London, for alleged involvement in the Gunpowder Plot against King James I. Contemporary records confirm his sentence of hanging, drawing, and quartering. Reports of a face appearing on the scaffold emerged soon after and became enduring English folklore.

Further Reading

Henry Garnet, 1555-1606 and the Gunpowder Plot by Philip Caraman amazon.co.uk

The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith in 1605 by Antonia Fraser (search via title) en.wikipedia.org

What the Gunpowder Plot Was by Samuel Rawson Gardiner amazon.co.uk

Kofi

Digging into this research takes time. If these stories matter to you, consider a tip on Ko-fi to keep them coming.