Discover the ancient Tzompantli skull rack of Tenochtitlan, where thousands of human heads were displayed as sacred offerings to keep the Aztec gods alive and the sun burning in the sky.

Imagine a world where your skull might be mounted on a blood-slick stake, where mothers whispered desperate prayers that their children would not meet such a fate, and where the sight of your severed head on the Tzompantli meant only one thing: you had been offered up, torn from life in a spectacle of blood and devotion. Whatever the reason, you can still see it in their hollow eyes, the terror, frozen in bone, staring back across the centuries.

Imagine a world where you had to keep the Gods happy and the sun rising each day and it involved carrying out brutal acts.

This was not madness. This was Tenochtitlan.

Turn a corner in the bustling marketplace, past vendors selling jade and cacao, and there it stood, the wall of human skulls stretching further than you could see. Their empty sockets stare at you. The smell of blood mingled with the smoke of copal, filling the air. This was the Tzompantli, and every face upon it had died, but not willingly. They had been sacrificed to keep the world spinning.

The Rack of the Dead

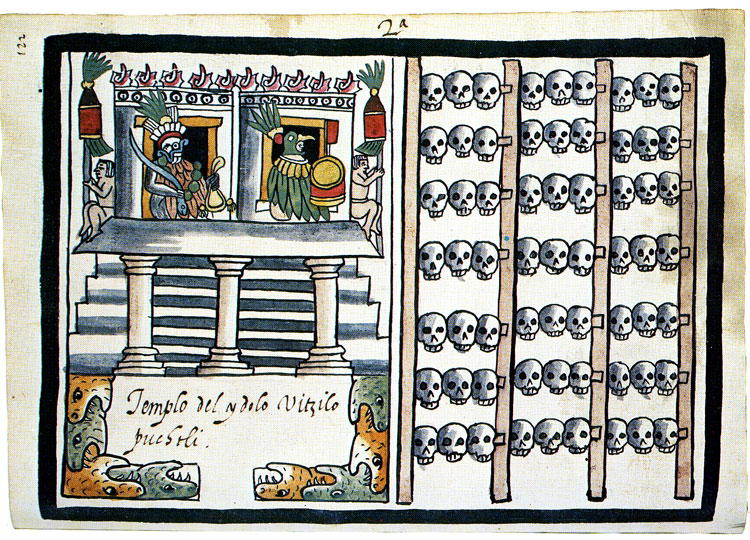

The word Tzompantli comes from Nahuatl, the Aztec language, meaning “skull rack.” It was a massive wooden structure, horizontal poles supported by vertical posts, with human skulls threaded through the temples like grotesque beads on a necklace that stretched further than a man could throw a stone.

These skulls belonged to sacrificial victims, most often captured warriors from enemy tribes. After their hearts were cut out in honour of the gods, whilst still beating, their heads were severed, boiled clean of flesh, and mounted upon the rack for all to see. It was a public declaration: the gods had been fed, and the empire remained strong.

The most notorious structure was next to the Templo Mayor, the grand double pyramid at the centre of Tenochtitlan, now buried beneath Mexico City. Built in the late 15th century, it was the focal point of Aztec rituals and was visible from nearly every part of the island city.

Feeding the Gods

To understand the Tzompantli, one must understand the Aztec worldview. They believed the universe was fragile. The sun would die unless nourished by human blood and hearts.

The primary recipient of these offerings was Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun, who required constant sustenance to fight off the darkness each night. But the rack also honoured Tlaloc, the rain god, and Tezcatlipoca, the lord of night and sorcery. Deities whose favour meant the difference between harvest and famine, victory and defeat.

Every skull displayed on the rack symbolised balance restored, the sun reborn for another day. The victims were said to journey to Tlalocan or Tonatiuhichan, divine afterworlds reserved for those who died for the gods. To have your skull mounted on the great rack was, in their eyes, an honour beyond measure.

A City of Skulls

When Hernán Cortés and his men arrived in 1519, they could scarcely believe what they saw. The conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote of thousands upon thousands of skulls, each drilled through the temples and threaded onto great wooden beams that groaned under their weight.

The Spanish priest Diego Durán described rows so vast they seemed to undulate like waves when the wind blew through the empty eye sockets. At night, locals whispered, you could hear them chattering, bone against bone, a chorus of the dead.

For the Aztecs, the Tzompantli symbolised glory, divine order, and the fragile line between life and death.

The Rediscovery

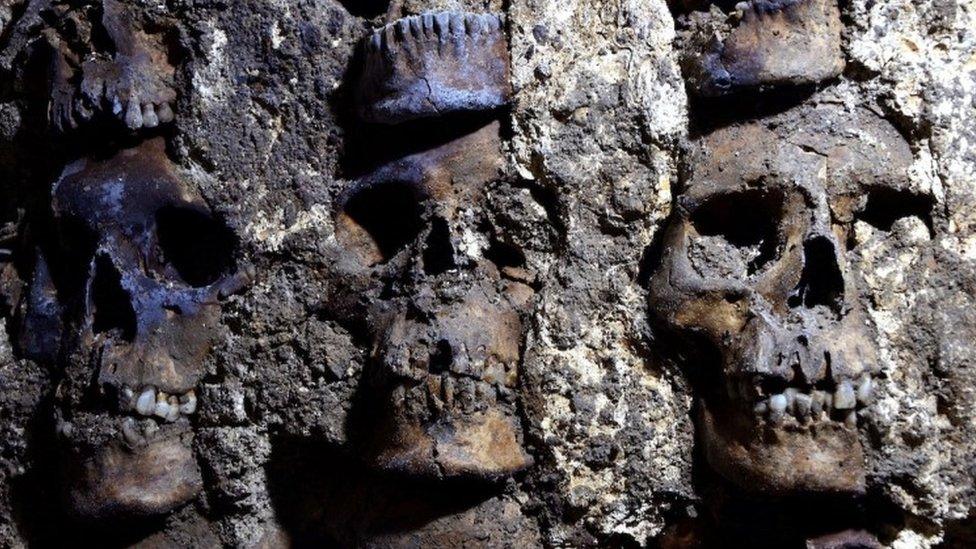

In 2017, archaeologists from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History discovered a tower of over 600 skulls near the ancient Templo Mayor. Many of the skulls belonged to women and children, indicating that sacrificial practices extended beyond captured warriors.

The skulls remain buried beneath Mexico City, carefully excavated and studied in situ by researchers. Each one is catalogued, photographed, and analysed before being preserved in the earth that has held them for five centuries.

This discovery challenged the belief that the Tzompantli was solely a military display. It was a spiritual offering to the gods by various people, symbolising a promise of the world’s continuity.

Legacy of Bone

To modern eyes, the Tzompantli may seem horrific. Yet for the Aztecs, it represented a unique beauty. A sense of peace. The balance of life and death, and the need to feed creation. It showed obedience to the gods.

Where skulls once gleamed under the sun, cars now hum through Mexico City. Yet beneath the asphalt, the past lingers, silent faces entombed in volcanic soil, watching and still waiting for the sun.

Dive Deeper Into History

If you loved this story and want to learn more about our insights and ideas behind this true history, consider checking out our Ko-Fi page.