They crushed her fingers to make her change her story. Those same crushed fingers would go on to paint the most violent female revenge scene in art history. Artemisia Gentileschi didn’t break. Not under the thumbscrews. Not ever.

She was raped at seventeen, tortured in court at eighteen, and forgotten for three centuries. She also painted the most disturbing masterpieces of the Baroque period. This is not a story of triumph. It’s the story of Artemisia Gentileschi.

It’s stranger than that.

Artemisia’s Revenge

Rome, 1593. A girl is born into a world of shadows, light, colour and oil paint. Her father’s workshop reeks of linseed and turpentine, and she learns to walk amongst canvases taller than herself.

When her mother dies, Artemisia is twelve. The workshop becomes her world. She grinds pigments with passion until her fingers bleed ochre and vermillion. She has talent that makes grown men nervous.

Her father watches her work and knows she needs more than he can teach. So he brings in Agostino Tassi. Experienced. Well-connected. Dangerous.

The Trial Of Agostina Tassi

In 1611, when she was seventeen, Tassi rapes her in a locked room. Afterwards, he promises marriage, clearly trying to absolve his ghastly act.

Artemisia Violated Refuses

What follows is worse than the rape itself. Seven months of public humiliation disguised as justice. Midwives examine her body like meat at market. She is poked, prodded and not believed.

Strangers debate her virginity in court as though gossip were the order of the day. To prove she isn’t lying, they bring out the sibille. Thumbscrews. Cords wrapped around her fingers, the same fingers that hold her brushes, and they are tightened, crushing her thumbs.

“È vero, è vero, è vero.” It is true, it is true, it is true.

She doesn’t recant.

Not once.

Tassi is found guilty. He walks free the same day. Justice has been performed, not served.

Then the Paintings Begin

Florence, 1613. Artemisia stands before a canvas larger than herself. She’s married now, to a mediocre painter who at least doesn’t hurt her. But marriage isn’t salvation. The canvas is.

She begins painting Judith.

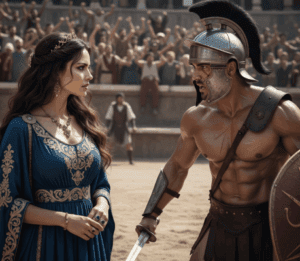

Judith: the biblical widow who seduced an enemy general, got him drunk, and sawed through his neck with his own sword to save her city. A popular subject for artists who wanted to paint female virtue triumphing over male violence.

The irony is not lost.

But not the Judith of other artists: delicate, disgusted, holding the sword like it might bite. This Judith grips Holofernes’ hair like she’s wringing laundry. Her arms are strong, peasant arms. The blood doesn’t spray artfully. It pours. It pools. It stains. The stains are reminiscent of something that has stained Artemisia’s heart since she was raped.

The Absolute Violence In The Paintings Mirrors Artemisia’s Pain

The maid isn’t cowering in the background. She’s pinning the general down with practical efficiency. Two women doing what needs to be done.

Critics call it “unwomanly.” They say no woman could paint such violence without having darkness in her soul. They’re right about the darkness. But conveniently forget where it came from. The very same violence Artemisia experienced. A silent violence that doesn’t die like the general clearly does. It lives on like a hidden rage.

Judith Murdering the General Is Painted Again and Again

She repaints it. And again. Seven times over her lifetime. Each version is more assured. Each Judith calmer in her violence. A type of sublimation that speaks of pain, but instead of dissolving the painter, it allows the painter to emerge and be seen. Nothing like the trial, which tried to diminish her power even further.

The Pattern

Look at her body of work.

Really look.

Susanna and the Elders:

A naked woman cornered by men who won’t take no for an answer. Unlike every male painter’s version, her Susanna isn’t posed for the viewer’s pleasure. She’s genuinely distressed. Her body language screams Get away from me.

Jael and Sisera:

A woman driving a tent peg through a man’s skull whilst he sleeps.

Lucretia:

Raped, holding the knife before her suicide. But in Artemisia’s version, she looks angry, not ashamed.

Every canvas bleeds with what she couldn’t say aloud. Each brushstroke is a testimony that couldn’t be silenced with thumbscrews.

To Learn More About Other Women That History Tried to Erase: Check Out This Post!

The Horror and the Beauty

Something is unsettling about standing before her paintings today. Not just the violence. It’s the recognition.

The way Judith’s face remains so calm whilst her hands do terrible, necessary work. The way the women in her paintings look directly at you, refusing to be objects of pity or desire.

Art As An Expression and Release

Art historians debate whether her work was revenge or simply an artistic choice. As if trauma and talent can be separated. As if a woman who had her fingers crushed to prove she was telling the truth wouldn’t paint hands that could finally fight back.

She became the first woman admitted to Florence’s Academy of Design. She worked in Venice, Naples, and London. She corresponded with Galileo. She raised a daughter alone after her husband vanished.

She survived plague, poverty, and the casual cruelty of a world that saw her as a commodity first, an artist second, a person last.

The Haunting

When Artemisia died in Naples around 1656, she left behind over sixty paintings and a question that haunts every canvas: What becomes of pain when you trap it in pigment and oil?

Her Judith doesn’t look like Artemisia. But look at her hands. Those are the hands of a woman who knows exactly how much pressure it takes to make someone let go. Those are hands that were tortured for telling the truth and learnt to hold a brush anyway.

For three centuries, her name was buried under attribution to her father, to her colleagues, to anyone but herself. Museum plaques read “Attributed to Orazio Gentileschi” over her signature. Her technique was too good, they said, for a woman.

Now her paintings hang in the Uffizi, the National Gallery, and the Louvre. Judith Slaying Holofernes draws crowds who stand transfixed by its violence. They take photos. They buy prints. They don’t always know the story.

But the painting knows.

Look at the blood on Judith’s dress. Look at how it spreads like testimony across silk. Look at how Holofernes’ face contorts in surprise. He never thought she’d really do it.

They never do.

The Truth

This is what they don’t tell you about trauma: it doesn’t make you weak or strong. It makes you precise. Every brushstroke of gore in her paintings is measured. Every splash of blood is deliberate. She painted violence the way only someone who has experienced it can, not with hysteria or melodrama, but with the terrible clarity of memory.

Women Refusing To Be Victims

When modern viewers call her work “disturbing,” they’re right. It should disturb you. It’s the discomfort of seeing women refuse to be victims in their own stories. The horror of watching them take back power with their own hands. Women should not be like this; they might gasp, confused. But oh, they are.

When pushed too far.

Artemisia Gentileschi Refused To Allow Pain To Be Her Story

Artemisia Gentileschi painted her pain, yes. But more than that, she painted the story of her pain. Perhaps it was a warning to all of those men who thought they had walked away free?

She couldn’t change what happened in that locked room in 1611. She couldn’t make Tassi pay for what he did. She couldn’t get back her reputation, her innocence, or the feeling in her tortured fingers.

But she could paint Judith’s hands, steady on the sword.

Again.

And again.

And again.

Until the whole world knew that some women, when pushed far enough, push back.

And when they do, they don’t miss.