Exploring the Vikings’ most brutal ritual execution — where archaeology meets ancient horror, and pain becomes worship.

In the frost-bitten dawn, a man is kneeling. His breath smokes in the air. Behind him, a warrior sharpens his blade on stone, slowly, rhythmically, like the drawing of breath before a scream. The smell of pine and blood fills the clearing. When the knife bites his back and the first rib cracks, he does not shout. He cannot. The lungs are next. Soon, they will flutter like wings. This was not a nightmare. It was worship.

Between the 9th and 11th centuries, the Vikings apparently perfected a ritual execution so grotesque that even their enemies could barely describe it. They called it the blóðörn, the Blood Eagle, a rite said to honour Odin himself. The truth of it remains contested. The terror of it does not.

The God Who Fed on Pain

To the Norse, suffering was not meaningless. It was divine currency. Odin, the Allfather, hung himself from the world tree, Yggdrasil, for nine nights, pierced by his own spear, to gain the runes’ wisdom. He tore out his eye and offered it to the Well of Mimir for sight beyond sight. This was not a god who spared himself, and so his followers did not spare others.

The Hardest Sacrifice Ever Known

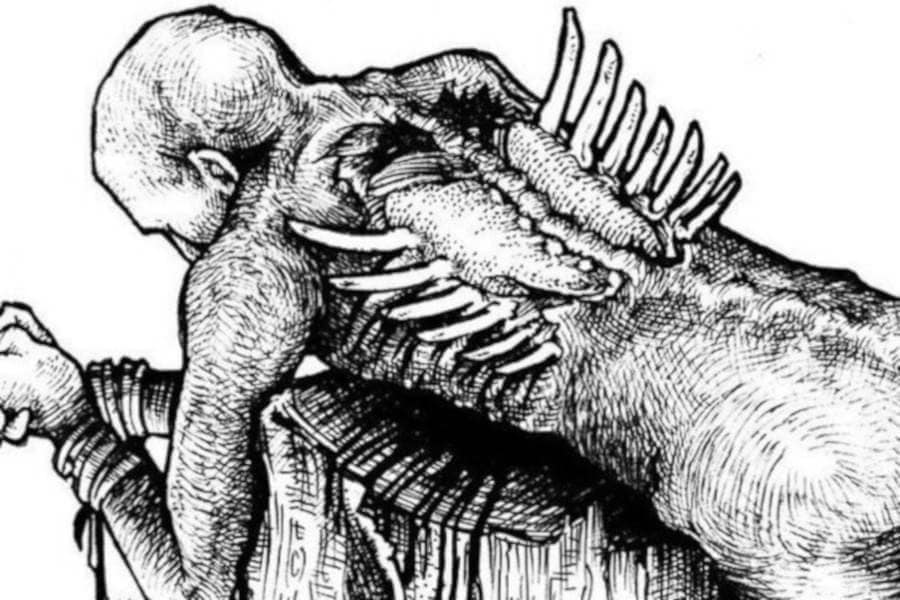

The Blood Eagle, according to saga and song, was not merely punishment. It was a sacrifice. The ribs were split from the spine, spread like wings, and the lungs were pulled through to resemble feathers. The symbol of the eagle, Odin’s messenger. Blood steamed into the cold air as if carrying the soul upwards.

To die beneath Odin’s gaze was to give one’s agony as tribute. Even the condemned could become sacred through endurance.

The Line Between Myth and Memory

Because myths matter when bones remember them. The sagas may have exaggerated the act, but something inspired them.

A ritual that unites suffering, theatre, and belief does not spring from imagination alone.

Earliest Written References

The earliest written references appear in the Ragnarssona þáttr and later in the Orkneyinga Saga, where Ivar the Boneless avenges his father Ragnar Lothbrok by carving the Blood-Eagle upon King Ælla of Northumbria in AD 867.

The story goes that Ragnar had been thrown into a pit of writhing snakes. His sons swore vengeance. Ælla’s back was opened in the shape of wings, his lungs displayed to the gods.

Historians still argue whether Ælla truly met this end, but the story itself served a purpose: to instil terror. It said: This is what happens when you defy the sons of Ragnar.

The tale survived because it was psychologically perfect: horrifying enough to linger, spiritual enough to justify itself.

A Death for Vengeance

Viking vengeance was ritualised, not impulsive. To kill was not enough; the death must carry weight and align with fate. The Blood Eagle was reserved for traitors and kings, those whose dishonour threatened divine balance.

The condemned, often bound upright or prone, faced slow mutilation. The ribs were cut beside the spine, peeled outward, and the lungs drawn through the gaps. Later medieval chroniclers claimed that salt might be rubbed into the wounds to keep the flesh from decaying too soon.

Chroniclers say the victim was forbidden to scream, lest he lose the chance of reaching Valhalla. Silence was his final test of courage. It was believed Odin would welcome him with open arms if he showed no fear or pain.

The Psychology of the Victim’s Mind

To imagine that moment is to step into a collapsing mind. The condemned man’s world narrows to heat, sound, and breath. His heart beats faster than the chants around him. Agony consumes language; time ceases to exist. There is only rhythm, the slice, the breath, the rip.

Modern research on torture survivors reveals the paradox: often, the anticipation of agony proves more destructive than the blade itself. When pain finally arrives, some describe it almost as relief, a terrible answer to unbearable dread.

Dissociation Fractures Reality

The brain, under such extremity, releases floods of endorphins whilst primitive defence mechanisms take hold. Dissociation fractures the psyche. Some victims even come to crave the pain as proof they still exist.

For those who believed in Odin, this descent might have felt like twisted transcendence. For the faithless, only terror and confusion remained as they watched their own “wings” rise. The Vikings understood this collapse intimately, turning death into spectacle, the ultimate control over body, soul, and memory.

The Archaeology of a Myth

Archaeology is often sceptical of legends and hearsay, but the bones don’t lie.

In Orkney, a male skeleton was discovered displaying deep, symmetrical incisions along the ribs beside the spine. Similar to that of the described ritual.

Cuts consistent with controlled separation. The remains date to the late 9th century, aligning eerily with the period of Viking dominance. Whilst not proof of the whole ritual, the evidence suggested deliberate post-mortem modification rather than random violence.

At St. John’s College, Oxford, a 10th-century mass grave revealed Viking skeletons showing trauma. These were not battlefield wounds. They were methodical, measured.

For decades, archaeologists believed the blood eagle was merely legend. Yet, it has since been shown that the act of creating the blood eagle is indeed possible, adding a new chilling layer to the story.

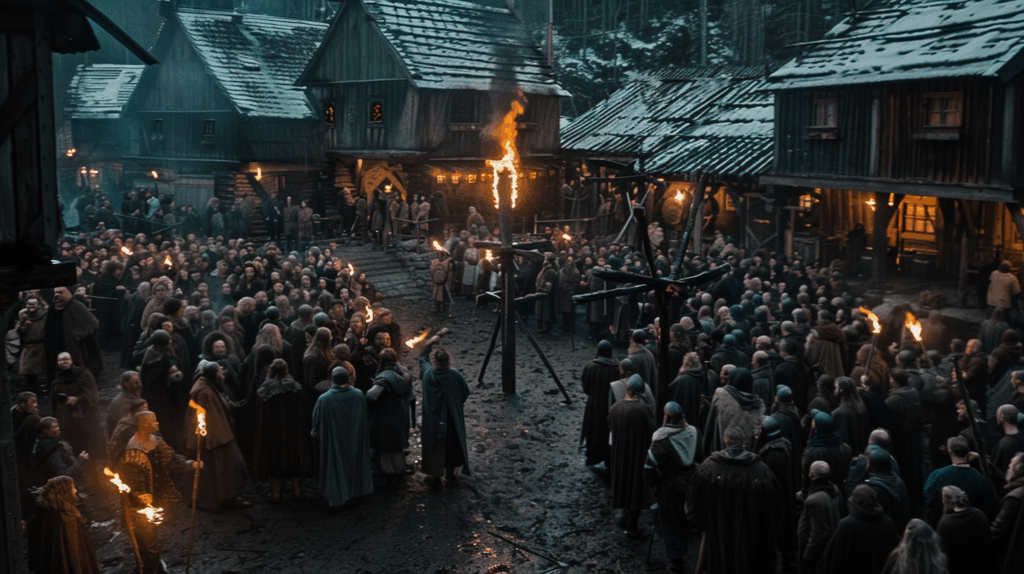

Pain as Theatre

The Vikings lived in a world where the line between the sacred and the savage was razor-thin.

Executions were public. Rites were communal. To witness suffering was to participate in divine justice.

Psychologically, such rituals reinforced group identity, a shared mythology of power, courage, and fear. When onlookers watched the Blood Eagle, they were reminded that death was not random, but moral. The gods demanded spectacle, and men supplied it.

In this way, horror became a tool of governance. The victim’s body was a stage, the knife a script, the blood a sermon.

Was It Real? Or Real Enough?

Sceptics argue that the Blood Eagle was a poetic invention. The sagas, written centuries after the supposed events, often blurred myth with memory. The term “carving an eagle on the back” could have been metaphorical, a kenning for killing brutally or claiming victory.

Yet dismissing it entirely risks underestimating the Viking mind. This was a culture that buried slaves alive with their masters, that sacrificed animals for prophecy, that sang to Odin with blood on the stones. Why, then, would the Blood-Eagle be impossible?

Archaeological hints, combined with the cultural obsession with honour and spectacle, make the ritual plausible, perhaps not often performed, but performed once would have been enough to seed legend.

The Legacy of the Blood Eagle

By the 11th century, Christianity crept through Scandinavia, softening the gods and civilising the blade. Yet even as Odin’s altars fell silent, the memory of the Blood Eagle persisted. Medieval monks, aghast and fascinated, recorded it as proof of pagan depravity, but also as a warning about the seductive nature of power.

The ritual became a mirror. To look upon it is to glimpse how faith and horror intertwine. It reminds us that cruelty, when wrapped in belief, becomes sanctified, and that men will always find poetry in their own brutality.

The Blood Eagle may never have soared in whole reality, but its shadow remains, carved not only in bone but in the part of the human mind that seeks meaning in suffering.