Before the lights and the laughter with our own Christmas traditions, there was only the cold.

To our ancestors, midwinter was not a season of celebration but a period of siege. As the sun weakened and the earth hardened into a tomb, the psychological toll of survival became unbearable.

The darkness outside the door was a physical attack. There was the threat of famine, disease, and things that moved unseen in the frost. Every tradition we now associate with festive warmth was forged in this crucible of pure, primal anxiety.

We do not decorate to be merry. We decorate because, deep in our collective memory, we are still terrified of what happens when the fire goes out.

Modern winter is a curated performance of joy and festivity, yet beneath the tinsel lies a quiet history of fear and worry. These rituals did not begin as celebrations, nor were they used as they are today. They were frantic psychological defences against the crushing weight of the dark.

1. Lights to Repel the Darkness

For three hundred years, the winter solstice was a period of high mortality. When the sun vanished, people did not light candles for atmosphere. They lit windows with flames as a desperate signal to the outside world that life still existed within the walls. A dark window meant a cold hearth and a house full of corpses. We now use fairy lights, candles, and other decorative lights, but they began as signals to the living.

2. Carolling as Warding

In Anglo-Saxon England, groups moved through settlements making as much noise as possible. This was not carolling as we know it, but performance as a survival tactic. Silence and darkness in the ancient winter were synonymous with death. By shouting and singing in unison, the community proved they were still a cohesive force. To be silent was to be vulnerable, and to be alone was to be a target.

3. Evergreen Decorations as Proof of Life

Bringing greenery into the home during the Iron Age was done for psychological appeasement. As food stores dwindled and the landscape turned grey and gloomy, the sight of something that spoke of life provided a vital buffer against despair. The branches were not festive ornaments. Instead, they reminded people that the world had not died off and greenness and life were still out there.

4. Feasting to Prevent Scarcity Panic

Ancient feasting was a brutal necessity born of logistical failure. Farmers slaughtered any livestock they could not afford to feed through the frost. This was a communal act of consumption designed to numb the village’s collective anxiety. We indulge today for pleasure, but the original feast was a way to drown the fear of the coming famine in fat and salt. Although admittedly, some fear the shops being closed for too long over the festive period!

5. Gift Giving as Appeasement

Gift exchange in Roman and Germanic traditions functioned as a bribe. During times of extreme scarcity, resentment and violence amongst neighbours were constant threats. Giving a gift was a peace offering intended to neutralise grudges before they turned deadly. It was a strategic move to ensure that the person next door did not become more dangerous than the winter itself.

6. Bells to Drive Away Harm

The ringing of bells from 600 CE onwards was a form of sonic cleansing. In a world where illness and famine were seen as invisible, malevolent forces, loud and discordant noise was thought to physically shatter the presence of evil. People rang bells because they believed the air itself was thick with things that would harm them.

7. The Yule Log as Controlled Fire

Fire was both a saviour and a potential executioner. The ritual of the Yule log allowed a household to focus their relationship with fire into a single, managed point of heat. It was an exercise in endurance and caution. Burning a massive log for days on end served as a countdown to the return of the sun, keeping the terror of a cold hearth at bay.

8. Costumes to Confuse Spirits

Iron Age mask-wearing served as psychological camouflage. During the liminal days of midwinter, it was believed that the boundary between the living and the dead grew thin. People wore animal skins and grotesque masks to hide their human identity. If a spirit could not recognise you, it could not claim you.

9. Moral Behaviour to Avoid Punishment

Between the ninth and thirteenth centuries, the pressure to be good at midwinter became a survival strategy. When life is fragile, any misfortune is easily blamed on moral failing. People behaved well because they feared that any sin might tip the scales and bring divine retribution in the form of a plague or a failed harvest.

10. Midnight Gatherings for Safety

Gathering at midnight was a response to the instability of the hour. In the medieval mind, midnight was a crack in time where the world was neither yesterday nor tomorrow. By huddling together in a church or hall, the community reduced their individual vulnerability. There was safety in the herd when the clock struck twelve.

11. Charity to Prevent Unrest

Medieval charity was a tool for social control. Winter hunger bred desperation, and desperation bred revolt. Wealthy landowners gave alms to the poor. Not to be kind, but to ensure that disgruntled masses did not burn down their gates. A type of living insurance. The winter months are a tough time for all, and during tough times, people can be angry. This soothed them and gave them a feeling of kindred spirit.

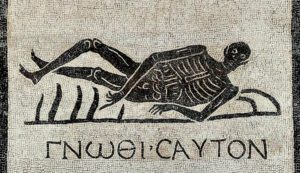

12. The Rewriting of Fear into Comfort

The Church did not ignore pagan terrors but rebranded them.

Between the fourth and eighth centuries, dread of the dark slowly reframed into a hopeful wait for salvation. We haven’t actually lost the original anxiety. We have just buried it under layers of doctrine. Christmas remains a season of high pressure because it was built on the frantic need to endure.

Winter has always demanded vigilance. The stress you feel today is the ghost of a much older survival instinct. We are no longer worried about wolves or spirits in the night, not literally for the most part, yet the ancient requirement for cohesion and performance remains. We are still just trying to make it to the spring.

Dive Into Our Substack for More

If you love what we do, then dive into our Substack for in-depth explorations of different True Ancient Horror tales.