Content note: This article includes vivid descriptions of historical violence intended to convey psychological and historical reality. Reader discretion is advised.

The Metal Taste of Shame – Bessie Tailiefeir

You are no longer a woman.

You are an example.

You are an example to that woman over there, the one who is talking a bit too much, sharing her opinions with everyone who will listen. You cringe inside. You want to tell her, ‘Talk, talk more, never keep quiet again. ‘

Right now, you appear as a vulnerable bird trapped in a cage. You are the least likely preacher they will listen to.

Your tongue is locked. Yes, that is it exactly. It’s locked against the lowest part of your mouth. It makes the back of your tongue bulge a bit, so you feel like you are suffocating from time to time. You try to cough, but it seems to block your nose.

Then the panic comes. It comes in waves, long, drawn-out waves. You feel breathless.

Ten pounds of cold, unforgiving Scottish iron is padlocked around your skull, pressing your jaw upward until your teeth ache. The cold Scottish wind whistles around your teeth, and it hurts.

Then comes the “bit,” a flat, rusted tongue press forced into your mouth; this is the bit pinning your tongue to the floor of your mouth. You cannot swallow. You cannot speak. You cannot even move your tongue to clear the pooling saliva. Within minutes, hot, humiliating drool leaks from the corners of your trapped lips, soaking into your bodice while the town watches you lose all dignity.

Your eyes pool with tears, but they are not sad tears; they are tears of anger.

You watch people point at you. You hear your name whispered as you go past ‘Bessie’. The contraption is doing its job and doing it well.

The Villain in the Shadows: Baillie Thomas Hunter

In 1567, Bessie Tailiefeir stood in the middle of Edinburgh and spoke a dangerous truth: she accused the city magistrate, Thomas Hunter, of being a cheat.

She was a brave woman; she understood what she was doing, and although she shook right from her toes to her neck, she spoke up.

Mistake.

”Hunter was using fake measuring scales to steal from the poor, you claimed.”

People listened. Some nodded in agreement but kept quiet, unlike you.

Another mistake.

The thing is, Hunter knew and understood the psychological power of the Branks.

Hunter had the last laugh. He knew very well that wearing this monstrosity did many things. It kept you quiet for one, but mostly it made you look like a raving lunatic.

He managed to retain his authority and, in the process, erased your agency. No one listens to a fool, he reasoned, and that is what you looked like now.

Bessie Tailiefeir

Except it hurt too. Not only did it humiliate Bessie, but it made her mouth feel raw, her teeth bled in pain, and her tongue’s drool did something strange to her psyche.

It played with her mind. Hunter had won.

The King’s Obsession: James VI and the Witch’s Bridle

This wasn’t just bullying or authority. It wasn’t just a local thing. It was supported by the highest power possible. So powerful it was close to God.

King James VI of Scotland, a man obsessed with the “unruly” nature of women and the perceived threat of witchcraft, elevated the Bridle to a weapon of the state. In 1590, he personally witnessed Agnes Sampson being tortured with a “Witch’s Bridle.”

While James wrote books on demonology, his officials were using iron rowels (spikes) to tear the tongues of women who dared to be “difficult.” For James, the silence of women was the only way to ensure the safety of the kingdom.

The Archaeologist Excavates

The Scold’s Bridle may have had different names, but no matter what you called it, the reason for its existence stayed the same.

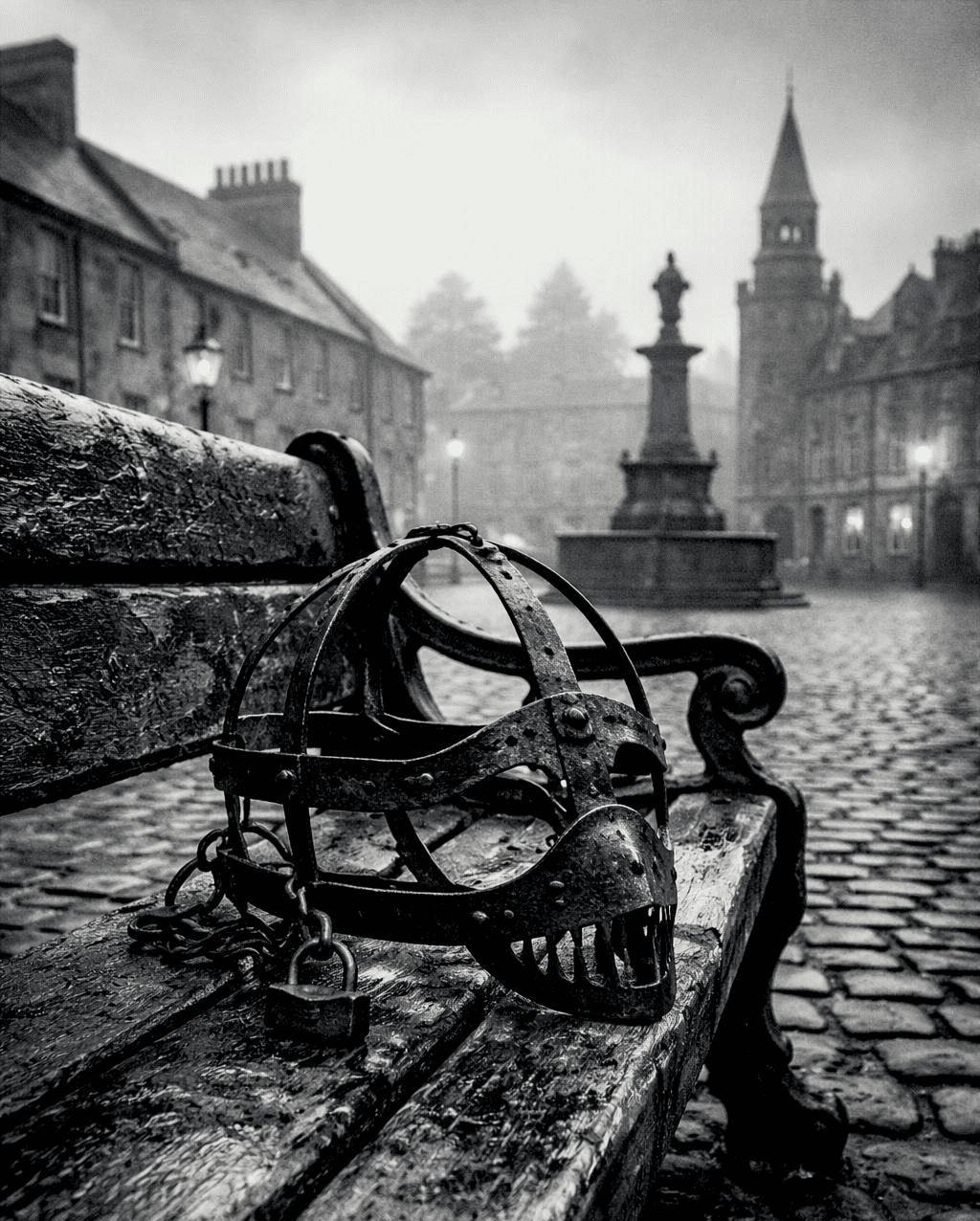

This wasn’t a mask in the way we imagine it. This was a cage designed to silence the wearer. The design was no accident.

A basic version would have a band of iron that opened via hinges at the side to allow the head to be enclosed. A flat piece of iron would then project out, which was placed in the wearer’s mouth to rest on the tongue. Other versions would become more elaborate, resulting in something closer to a cage than to a headpiece, while retaining the basic format.

Some Were Iron Masks

The most bizarre versions were more like an iron mask, with holes cut for the eyes and mouth. All of them had the same piece of iron to be placed in the mouth, but some models were more severe. They had spikes that forced the tongue into an unnatural position. This was intended to increase the discomfort the wearer would experience, to make them think twice about speaking out again.

These spikes were known as rowels. If you did attempt to speak, the natural reaction of your tongue would mean it pressed against the spike. This would lead to your tongue being cut, so you had no option but to stop speaking. Move, and you would bleed.

After the fitting, the cage was snapped shut and padlocked.

Its First Usage

The first recorded usage of the Scold’s Bridle in Scotland was in 1567 with Bessie Tailiefeir. The device also eventually moved to England, but only significantly later, with the earliest recorded mention in 1623.

By the end of the 16th century, any reasonably sized town in Scotland would have had a Branks. Some would even have it on display at the Mercat Cross, since that was the real hub of the town, where it would be seen as a deterrent to women.

The Fitting: A Social Lobotomy

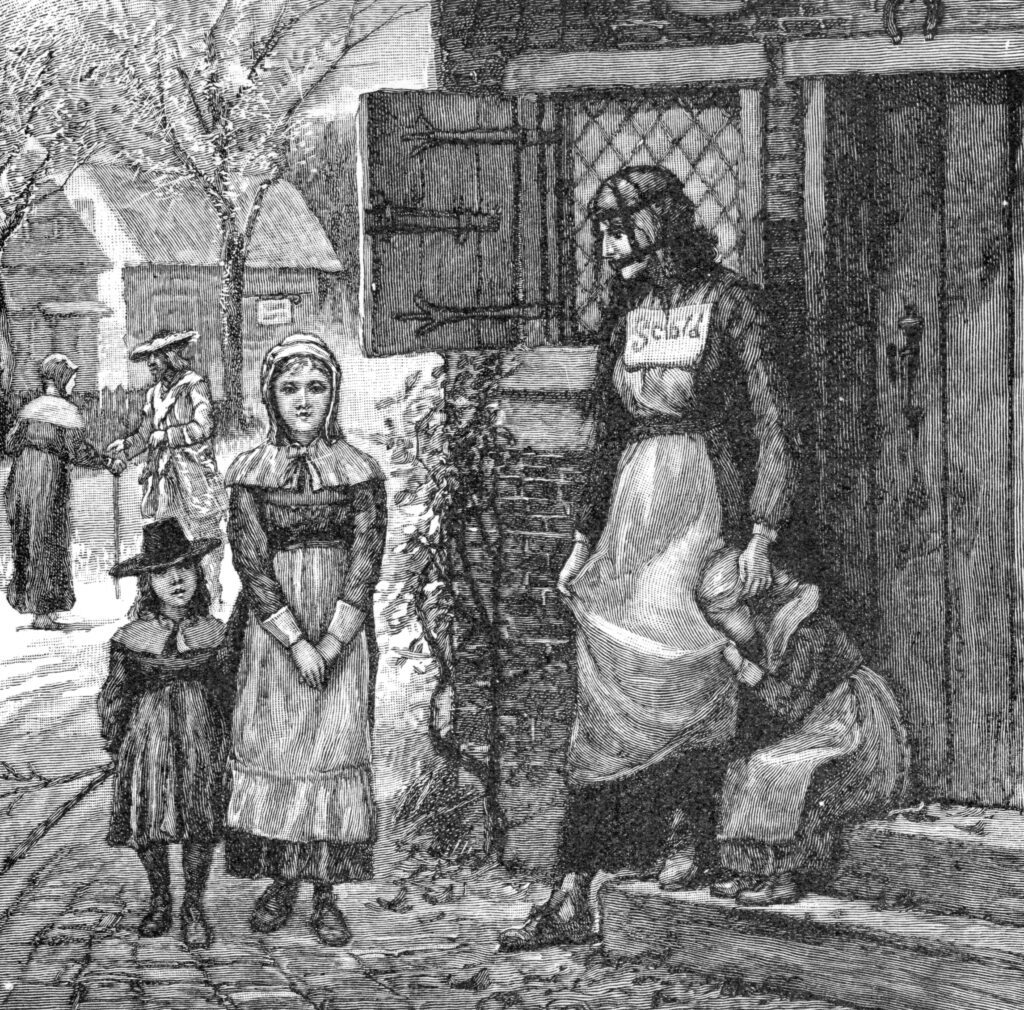

The “Branker” didn’t hurry; he enjoyed the theatre of the fit. He adjusted the hinges behind your ears, tightening the iron straps until the skin on your forehead puckered. The cage was a “one size fits all” nightmare, designed to leave deep, bruised indentations in your temples. As the lock clicked shut, the psychological reality set in: you had been “un-personed.” To the Kirk and the crowd, you were no longer a neighbour. You were a “Scold,” a domestic animal that needed breaking.

The Forensic Reality: How It Broke the Body

The intention here was to ensure the wearer suffered. The cage would be tightened around their head until the iron pressed against the skin. There was undoubtedly a sense of being trapped inside, but that was only part of the torture.

Your jaw would also be held in a particular position. Exactly how it would be held depended on the version and model. However, you would suffer, but the iron would never quit.

After hours of being forced into a fixed position, the facial muscles would begin to spasm. To the superstitious 17th-century crowd, these involuntary twitches looked like “demonic possession,” justifying even more cruelty.

Who Wielded This Weapon?

Even though this device was often linked to husbands wanting their wives to stop nattering, the husbands did not have the option of placing it on their wives’ heads. Instead, it was left to certain officials in the town.

The primary individual would be the town magistrate.

At this time, there was no police force, and the meting out of punishments was usually left to the local magistrate. They were local government officials who wielded significant power. The local Kirk sessions would also play a role, particularly with specific accusations, while the local beadle, who was a parishman and also sometimes the town crier, would then fit the device.

Who Were the Victims?

The scold’s bridle was a device aimed at women, and there were several reasons why you may find yourself trapped inside this cage.

First, a woman who was deemed as too loud or “nagging” her husband could find herself in trouble. Women who were deemed dishonest or corrupt by others could also encounter the device. Remember, these were women who had been deemed as corrupt by church officials or other prominent locals, and there didn’t have to be any absolute truth to the matter.

Women who had been called witches could also encounter it, which is why some called it the witch bridle, but wearing it would be the least of their worries.

Other victims of the Bridle include Dorothy Waugh, a Quaker woman who in 1653 was put in the device for eight hours by the Mayor of Carlisle, simply for preaching in the market. He reportedly said she had a “vicious tongue.”

How Long Did They Have to Wear the Scold’s Bridle?

Records indicating how long the individual had to wear the scold’s Bridle are rare, but in the case of Bessie, we know she was fixed to the Mercat Cross in Edinburgh for one hour. By fixing her there, she was in full view of everyone, and people could throw stones at her to show their loyalty to the local government.

Women would not be forced to wear the scold’s bridle for a substantial period of time, but try wearing this device with drool running out of your mouth and pain hitting you every time you inadvertently move your tongue, and you begin to understand it is a device of torture.

The scold’s Bridle was used as a warning for centuries. The last recorded usage was in 1863, some 300 years since Bessie became the first.

The Psychological Insight

The Scold’s Bridle as Identity Erasure

In this harrowing account of Bessie Tailiefeir, the following psychological analysis offers an informed perspective on the likely internal and social processes at work during this punishment.

Identity Disruption Through Enforced Silence

The scold’s Bridle was not primarily a device of physical punishment but of psychological control. Its function was to alienate the person from themselves. Forcing them to accept that what they did was wrong, then to close the very orifice through which thoughts and ideas are shared, the mouth. This is not only humiliating but also infantilising.

By criminalising speech itself, the state declared a woman’s thoughts and inner life illegitimate and dangerous. The punishment targeted the face deliberately. That is how we recognise each other and hear each other. It is the face and mouth that get us through life, get us seen.

Public Punishment and Collective Compliance

This constitutes a historical form of gaslighting. The physiological effects of the torture were used as evidence of moral or psychological deviance.

Distress became proof of guilt. Silence became proof of submission. You were essentially trapped.

The contraption encouraged public humiliation and was a signal to give them the green light. Once the mask was spotted, you were fair game, and people in a group can be ruthless.

It was also a signal of conformity. People could see what happened to people who stood up and spoke about what they believed in.

Aftermath: Social Erasure

Once the iron was removed, the harm lasted. People perceived women differently after this. The outcast, the crazy one, the one who baulked at authority.

In a small community, the comeback from this was impossible. You were forever labelled by the spectacle that had occurred. It dehumanised you.

The Legacy: The Silence Remains

These contraptions are long gone, sitting as silent as always in museum cabinets.

But the saga continues. We have traded iron cages around the face for social media silos and shame-piling. Most of this targets women, but they target everyone. The goal remains the same. To turn a woman or person into a spectacle or target. So that the collective can feel safe in righteous attacks on individuals, whilst still within the safety of the group. The mob mentality persists just as strongly as it did in the 16th century.

Love a Deep Dive Into History?

If you love a deep dive into history and want to explore from the point of view of archaeology and psychology, you will want to check out our in-depth study of Janet Horne by visiting our Substack.