The Night They Came for Janet Horne

It was summer in the Highlands when they came for her. Darkness would only visit for a few hours, people were more active, even their imaginations it appears. Janet Horne was half awake, half drifting through the fog that had settled over her mind in recent years.

She was an older woman whose memory was failing long before the world had a name for dementia. Some days, she forgot faces she had known all her life. Some days she wandered away from home and had to be led back gently. Most days, she sat by the fire with her daughter, trying to keep the cold out of their bones. She was a nice woman. People liked her, but lately she had been strange.

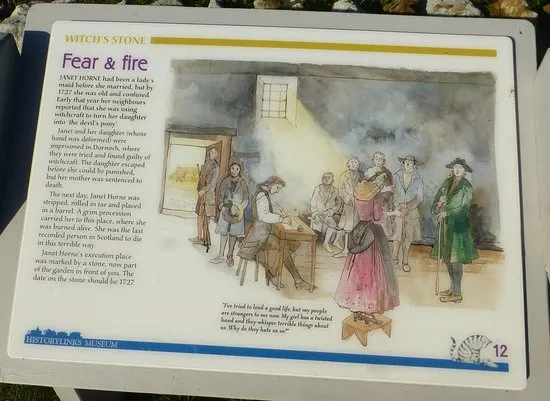

In Dornoch, a small town where every door was familiar and every misfortune needed a culprit, Janet’s confusion became a spectacle.

Her daughter had been born with twisted hands and stiff joints. She struggled to thread a needle or lift a pot. Janet helped her with everything.

Their home was a place of quiet survival, built on care, whispered prayers, and small acts of charity offered to the neighbours who would later, Janet didn’t realise, turn against her.

That summer, a rumour began to slither through the town like snakes beneath a door. A neighbour said Janet seemed strange. Someone else said her daughter’s deformity looked unnatural. Someone recalled seeing Janet muttering to herself in the yard. Not realising that she was obviously suffering from an illness. From these fragments a monstrous lie took shape, a story so grotesque it would be laughable if it had not led to a death.

Her daughter’s hands and feet had been the trigger.

They said Janet had shaped her daughter into a pony and ridden her to meet the Devil.

A Mother, a Disabled Daughter and a Town Hungry for Blame

The accusation grew with frightening speed. In a community with limited education and deep superstition, the daughter’s hands became proof, and Janet’s confusion became guilt. It did not matter that they were poor. It did not matter that they were harmless. It did not matter that Janet’s only crime was age and the failing of her own agency.

The sheriff arrived with a trial already decided in his mind. What followed was not a search for truth. It was an administrative tick box. There was no legal counsel, no appeal, no careful weighing of evidence. Janet’s wandering answers, both vague and nonsensical, born of illness and age, were recorded as contradictions. Clearly, something was up. Obviously, she had shaped her daughter into a pony. She was asked to recite the Lord’s Prayer, but fatally she made a mistake, just one small mistake. To the sheriff, that error was proof she was a witch, that is how flimsy the “evidence” could be.

The daughter, who depended on her mother for everything, was arrested as well.

Before the sentence could be carried out, the daughter fled. History does not tell us where she went or whether she survived. It only tells us that she ran into a world where a disabled woman alone in the Highlands had almost no hope of safety.

Janet could not run. Age held her in place. Confusion held her in place. And the neighbours who had once accepted her charity now watched with cold silence.

The Parade Through Dornoch

Janet Horne was paraded through the streets before her execution. People gathered as if it were a spectacle. They watched from windows and market stalls. Some witnesses later claimed she laughed, but this was almost certainly invented to soothe the consciences of those who allowed her death.

A laughing witch is easier to burn than a terrified older woman whose mind is slipping away.

She was tarred. Tar burned long before the flames were lit. It soaked into the skin, making breathing more difficult. In her confused mind, Janet Horne must have tried to make sense of what was happening. Tar ensured a quick ignition. It ensured suffering. It turned a human being into fuel.

The Fire

The stake was raised in an open place near the town. Flames climbed her clothing and hair with terrifying speed. Witnesses saw a bright, roaring fire. For Janet, it was terror, pain and confusion in the final moments of her life.

She died without understanding the reason. She probably tried to understand why her neighbours and friends suddenly hated her. She died without the comfort of her daughter. She died because a rumour had become a fact, and ignorance had sealed her fate.

Her death was one of the last legally sanctioned witch-burnings in Britain. The Witchcraft Act would be repealed less than a decade later, but not soon enough to save Janet Horne.

What Remains?

A modest stone in Dornoch marks the place where she was burned. Sadly, the stone has the wrong date, 1722, when she had met her end in 1727.

People leave flowers now. Some visitors pause. Others read the inscription and walk on. The stone cannot convey the truth. It cannot explain the smell of burning tar that hung over the town that day. It cannot recall the daughter running into the hills.

It cannot show the face of an older woman, terrified by accusations she cannot understand.

Janet Horne was not a witch. She was a mother, a caregiver and a woman living with an illness no one recognised. Her death was not justice. It was fear dressed as righteousness.

Her story survives because it forces us to confront how easily a vulnerable person can be destroyed when society decides she is other.

To read more about how the law changed, see our Substack.