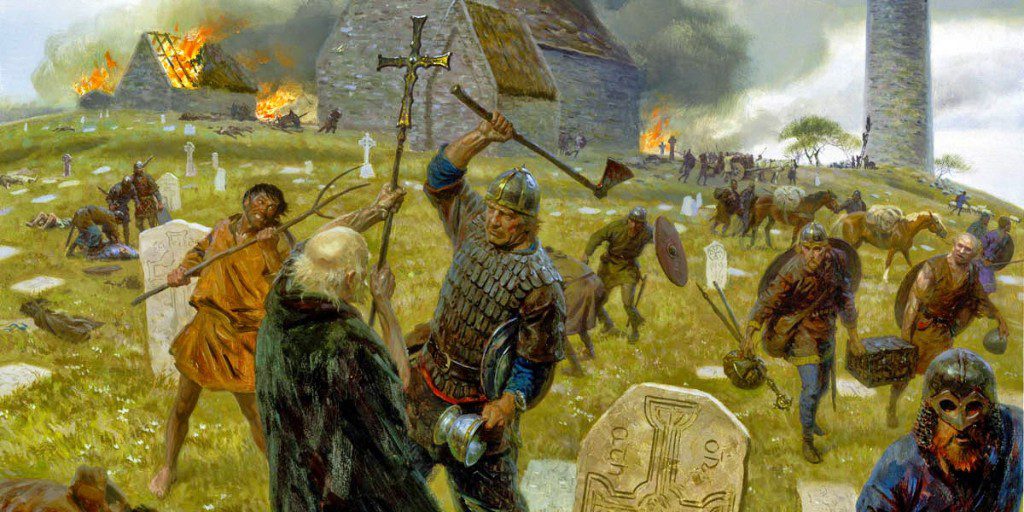

Some monks were cut down at the altar. Their robes soaked through in seconds. One was found with his arm severed at the elbow, the limb thrown aside as if it were driftwood on a beach.

The Christmas Eve Massacre of the Iona Monks

Christmas Eve 986AD should have been a night of prayer and reflection on the island of Iona. A cold mist lay over the monastery, winter covered the landscape, candlelight trembled against damp stone, and the monks prepared for the most sacred moment of the Christian year.

Then an unfamiliar sound broke the quiet. Oars. Heavy steps on shingles. Voices carried on the wind. Before the community could react, the Vikings had already reached the cloisters. Once there, they didn’t hesitate.

This was the fifth time Iona had been attacked. The monks knew fear, yet the ferocity of this raid was unlike any that had come before. By dawn, the abbot and fifteen monks were dead. Their bodies lay across the sacred spaces they had served for decades.

The Long Shadow of Viking Raids

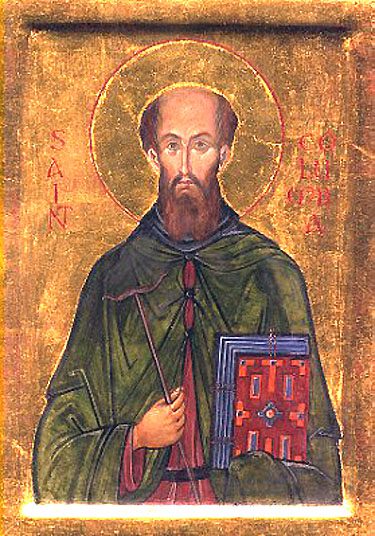

Iona was one of the most important spiritual centres in early medieval Britain. Founded by Saint Columba in the Sixth century, it became renowned for scholarship, illuminated manuscripts and prized relics.

It was also wealthy and exposed to the sea, which made it a target.

The Vikings struck in 795AD, then 802AD, then 806AD, when they killed sixty-eight monks, then again in 825AD. Each attack stripped away treasures and lives.

The monks buried relics, hid manuscripts and rebuilt again and again. By 986AD, they lived with constant anxiety, even though the Viking raids had ceased for over a century.

The attackers knew exactly what they would find. Iona still held manuscripts, jewels and sacred objects that held cultural and economic value. And the monks were not warriors.

A Rumour of Betrayal?

The early church was not free from political conflict. Ireland, at the time, was divided by competing monastic groups and it’s said some monastic groups in Ireland wanted to weaken the monastery on Iona. Abbots held land and influence. Rivalries ran deep. Some historians have suggested that monks loyal to a Danish Irish king may have encouraged the raid on Iona.

If the abbot and his leading circle in Iona were removed, power would shift. Nothing was proven, but the theory endures. The very idea that Christians may have set a Viking attack in motion remains one of the darkest ideas in the story of Iona. Nothing is proved, but the theory is strong.

The Night of Blood on Iona

It began with a single scream that never finished. The Vikings would have poured through the cloisters with a speed that stunned even the monks who would have known about the raids on the monastery in previous centuries. The Vikings were ruthless. Their blades would have risen and fallen in fast, ruthless arcs.

When metal met bone, it made a dull, cracking thud that echoed across the courtyard. Candles would have toppled. Hot wax would be spilt. Shadows jerked and twisted across the walls as men died where they stood.

Some monks were cut down at the altar. Their robes soaked through in seconds. The monks would have been mutilated and their bodies discarded as if they were driftwood on a beach.

Other monks may have fallen on the stone steps with a deep cut across their body. We do not know their precise injuries, but Vikings would spare nobody. Inflicting pain and horrific injuries would not phase them. Contemporary accounts even mention that this raid in 986AD was brutal and bloody.

Bodies would have lain half curled, as if their last instinct had been to shield themselves or to reach for a holy object. Others lay flat, cut clean through cloth and skin. The cold night air mingled with the smell of burning parchment and the heavy, choking scent of blood pooling across the stones.

The Vikings kicked through the fallen as they searched for treasure. Their boots left dark tracks that marked their path.

The abbot was not spared. He never stood a chance. The attackers showed no mercy. They ended him where he stood.

The survivors later wrote that the sound was worse than the sight. Not the screams, but the sudden drop into silence when they stopped. Only the crackle of a torch and the slop of water against the shore broke the stillness. It was a silence so complete that it hollowed out the heart of the island.

What Survived After the Iona Massacre

The attack shattered the community, yet the legacy of Iona did not die.

Survivors fled to other monastic centres such as Kells, where scribes continued their work. Some believe that parts of the Book of Kells were produced by monks who escaped earlier Viking violence on Iona. Scholarship travelled even when the island burned.

Over time, the monastery was rebuilt. Pilgrims returned. The remaining relics were restored to honour. But the memory of Christmas Eve 986AD remained like a scar beneath the island’s calm surface. The cruelty of killing so many on such a holy day was not lost on them.

A Warning from the Past

The Christmas Eve Massacre is a reminder that holy nights have never been immune to human brutality. In 986AD, a sacred moment collapsed into terror. The Vikings left behind bodies, stolen treasures and a silence so deep that it unsettled the island for generations.

Today, visitors find peace on Iona. Waves whisper against the shore. Grass moves gently where cloisters once breathed with life, prayer and reflection.

Few realise that beneath their feet lie the memories of a night when prayer gave way to violence and the island learned how fragile sanctuary could be. But no matter what, faith and the spirit can never be truly broken.