A Horror Seven Thousand Years Old That Prehistory Tries to Turn Its Face From

There are moments in archaeology that feel wrong, moments that do not fit the world they come from. Schöneck-Kilianstädten is one of them.

Seven thousand years ago, someone created a pit that should not exist, a pit that contradicts everything we thought we understood about the gentle, agrarian Linearbandkeramik culture. When archaeologists removed the layers of earth above it, they uncovered bodies thrown in without care or ceremony. Legs were broken deliberately, brutally, violently.

Children’s legs were smashed, so they could not run. It was not a burial. It was extermination.

This is the kind of discovery that forces scholars to stop, re-examine everything they thought they knew, and ask the question no one wants to answer. What happened here, and why did a peaceful Neolithic community reach for such calculated brutality?

Who the LBK Were Before the Pit

The Linearbandkeramic culture, also known as LBK, was a culture that spread quite rapidly across Central Europe in the sixth millennium BC. It was a culture that focused on farmers, and they built longhouses for their community. They also made pottery containing painted bands, hence the LBK name, and they grew crops. They were the first real stable farming villages north of the Alps.

For decades, textbooks described the LBK as stable and relatively harmonious. There were encounters with hunter-gatherers, yes, and occasional evidence of conflict, but nothing like organised slaughter. Nothing that hinted at massacres carried out with deliberate cruelty.

This is what makes Schöneck-Kilianstädten so disturbing. It breaks character. It forces us to confront a rupture inside a culture that was never meant to be violent on this scale. It makes us look at our past differently.

What the Archaeologists Found at Schöneck-Kilianstädten

In 2006, research teams from the Universities of Mainz and Leipzig were carrying out a survey ahead of construction when they uncovered the pit. This is common in archaeology, but nobody would ever expect to uncover a site such as this.

At first, it appeared to be another Neolithic grave, a common enough feature in the early farming landscape. But the bones did not lie peacefully. They were scattered, tangled, overlapping, and twisted. This was the opposite of what you would expect from the LBK. They would generally buy people on their left side and with grave goods. None of that was present here, indicating something else was going on.

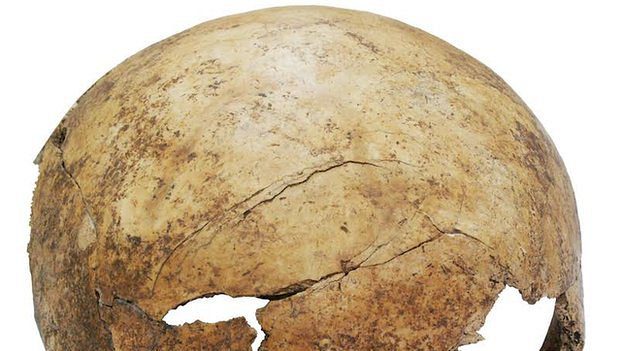

Twenty-six individuals were present. Men, women, adolescents, children, and infants. No one had been spared. Most of the adult skeletons showed signs of lethal blows to the head, perhaps from clubs or axes.

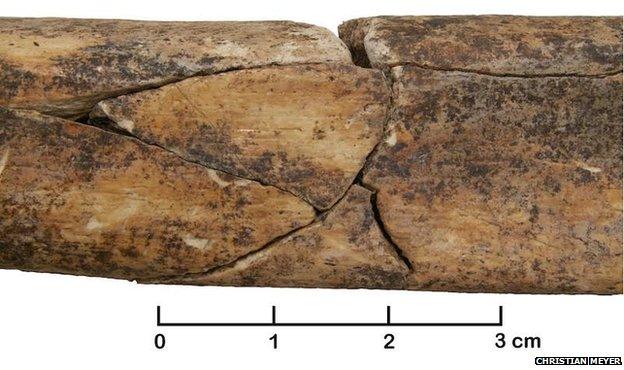

But the most chilling detail was the legs. Many of the victims had lower leg bones that were intentionally broken. In children, the breaks were particularly clean, inflicted while they were still alive.

This was not execution. This was immobilisation. A deliberate decision to prevent escape.

The bodies had been dumped. Not placed, not arranged, not honoured. Dumped. The message was clear. You do not matter.

Violence That Did Not Fit the Pattern

For a culture commonly viewed as organised and stable, this massacre is a shocking aberration. LBK villages were long-lived, built on cooperation and shared agricultural labour. Most of their known burials are controlled, careful, and structured.

The violence in Schöneck-Kilianstädten feels personal. It feels as though a line was crossed, and once crossed, it could not be uncrossed.

But then the archaeology grew louder. Schöneck-Kilianstädten was not alone.

Other Graves That Should Not Exist

Across Germany, within the same culture, archaeologists have found other LBK mass graves showing similar patterns. Talheim. Herxheim. Schletz Asparn. It’s insane, and who knows how many others lie there just waiting to be discovered?

Each one reveals echoes of the same brutality. Blunt force trauma. Bodies tossed into pits. Signs of terror and flight. Evidence that victims were not killed in orderly battle but hunted, immobilised, and discarded.

Talheim is sometimes called the Stone Age Death Pit. Herxheim contains evidence of possible ritual cannibalisation. Schletz Asparn shows fortified ditches filled with people who died as they ran. These sites form a constellation of inexplicable violence that cannot be dismissed as a singular tragedy or merely a coincidence.

Whatever ruptured this apparently calm LBK society, it was not an isolated event. It was a pattern, and we are only discovering it now.

The Day the World Changed for Them

Archaeologists believe the group at Schöneck-Kilianstädten were attacked by another LBK group. Not by outsiders. Not by wandering hunters who simply stumbled across this village. This was neighbour against neighbour. People who spoke the same language, tilled the same soil, used the same pottery, and lived only a short distance away.

The presence of children is significant. Children do not get caught in formal warfare in this period unless the violence is intimate and intended to eliminate a lineage. In battle, they would be nowhere near the violence. However, this site shows they were in the middle of it all.

The broken legs suggest systematic disabling, almost certainly done during the attack itself, not after death. It implies fear. It implies panic. It implies an urgent need to stop these children from escaping.

That level of intent is not chaos. It is a strategy. It is a calculation. And that is the most chilling realisation of all.

What Could Have Driven Them to This

We clearly do not know the exact cause, but archaeology can give some hints as to the possible reasons behind this massacre.

First, it could be population pressure, and while this sounds crazy given the global population at the time, it’s still possible. Early farming was stable, but we were still learning. If a community believed they had the perfect land, good soil, a reliable water supply and so on, that became gold. Other communities would want that land, and if there was a failing harvest, that panic could have driven a community to attack another group.

Another possibility is boundary conflict. LBK longhouses follow a precise layout. They signal ownership. Territory. Identity. If one village expanded too far or built too close, tensions could flare into violence. Even back then, people were very protective of what they owned. It could easily push another group into taking this drastic action.

A third possibility is cultural fracture. The LBK were not a monolith. Some communities may have adopted new practices or new belief systems. Others may have resisted. A dispute over ritual, status, or inheritance could escalate, particularly in tightly woven settlements where everyone knows everyone else.

But you also cannot rule out the possibility of this being personal, but some group then took it to a whole other level. In an early farming village, a family feud could escalate into a larger problem involving the entire community. Add in the possibility of scant resources, and you have a pressure cooker waiting to blow its lid.

Yet, no matter the reason, one thing is clear. This was a deliberate attack.

The Psychological Weight of the Evidence

With archaeology, the story can be uncovered in different ways and formats. In this case, it’s the bones that tell us so much about what happened at this site thousands of years ago.

By all accounts, these people should have been living an active life, farming and building a society. There would have been a routine in place not only to survive, but also to thrive. Yet all of that was stripped away by someone else who displayed unimaginable cruelty and disposed of these people as if they were nothing more than waste.

But out of the entire site, it is perhaps the bodies of the children that hit hardest. All of it is horrific, but knowing these ten children met a horrible end with bones shattered and skulls smashed blows our mind. They wanted to disable even the children so they could not escape. Whoever attacked this group wanted to ensure nobody could survive.

They carried out this attack with absolute precision.

The Legacy of Schöneck-Kilianstädten

The site stands today as one of the earliest known acts of genocide in Europe. It forces us to acknowledge that violence is not a late invention. It lives deep in human history, even among societies we once thought peaceful.

Yet it also reveals something else. The LBK were capable of beauty, cooperation, farming innovation, and cultural cohesion. They were also capable of collapse.

To understand them is to understand ourselves and how societies evolved thousands of years ago, which ultimately led to what we have today.

The Final Question

The pit at Schöneck-Kilianstädten has the ability to leave us with so many questions that go beyond archaeology. What actually happens to a society that was once stable but is now under pressure? What forces people into making specific choices when their land, food, or even their identity is challenged? How far will they go when their very survival may depend on their actions?

We do not know who struck the first blow. We do not know the spark. But we do know the outcome. Twenty-six people, thrown into the earth, their story preserved in silence until the day the soil gave them back.

A warning from seven thousand years ago that even peaceful worlds can break.

Learn More On Our Substack

Check out our Substack for more details on not only this site, but other horrific archaeological discoveries from around the world. Also, get some of our insights into what is going on with the sites.