From high-pitched ringing to wild dogs barking, what was the cremation atmosphere really like?

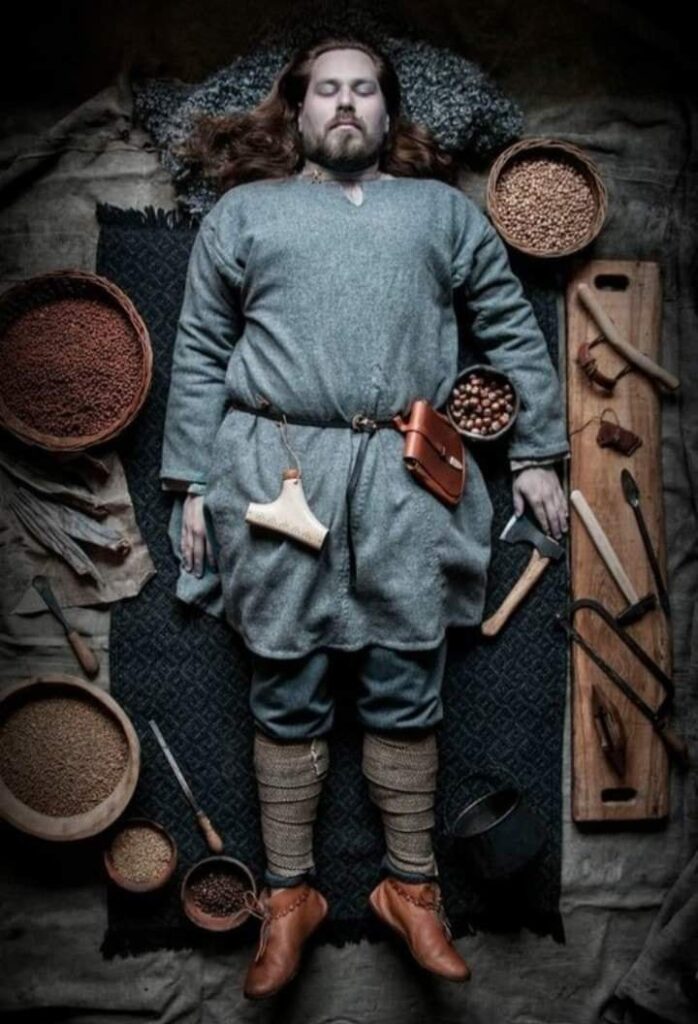

The Vikings thought fire was cleansing and also merciful. The beginning of a journey that all Vikings eventually wanted to pursue. Death did not disturb them in the least. One clean cut between flesh and spirit, bones falling soft as ash, smoke carrying the soul upward into the night. Viking cremations were a central part of their beliefs.

The goal: Valhalla. The afterlife is where only the best people go after death. Valhalla was paradise.

The Reality Of A Viking Cremation

But the reality of cremation was harsh to watch, body bursting open in the flames, skulls splitting like dropped eggs, teeth shattering through the heat with sounds that made hardened warriors flinch. Some bodies simply refused to burn.

And on the worst nights, when the pyres failed, and the wind turned the wrong way, the dead made noises that no living throat should ever produce.

Fire was the best method to get a good person to the kingdom of Valhalla. Fire was sacred.

But fire is never obedient.

In the grey winters and the soaked spring seasons, when the wood was never quite dry enough, and the wind blew in from the wrong direction, the flames did what flames do. They failed, and they failed spectacularly.

What followed were sounds that settlements remembered for generations.

The Roar of a Fire That Stopped Behaving

A Viking pyre could reach temperatures between six hundred and a thousand degrees when it was built the right way.

Fat, cloth, timber, oxygen, all feeding each other until the flames stood taller than two men and drowned out every voice. Ibn Fadlan, an Arab diplomat, watched Norse funerals on the Volga in 922 and wrote of heat so intense it seemed almost alive. On a still night, the roar of a massive pyre carried across water for miles.

The Strange Cries And Crackles Would Have Unerved People

Picture that pyre on a Danish or Norwegian hillside, where strong coastal winds blow in suddenly. If stacked too high, it might lean or topple, spilling burning limbs. If packed too tightly, it acts like a chimney, driving the flames downward and turning it into a groaning furnace with each gust.

The heat could become so concentrated in one spot that it scorched the earth beneath black.

Families stood around these pyres with their cloaks wrapped close, faces turned away from the heat, listening to the fire roar like a living beast. They believed it was the dead man’s strength rising one last time. They had no idea about science and noise.

What Bones Do When They Boil

Bone is not quiet in fire. Bone is full of moisture, full of trapped air, full of pockets that have nowhere to go when the heat arrives. When a body comes into direct contact with flame, the skin blackens and splits.

Fat catches light. Muscles seize and pull tight. There is a moment when the pressure inside has built up so far that it simply has to break. That is when the cracking starts.

Modern forensic reports describe a high-pitched ringing when long bones fracture under heat. Vikings would have heard that sound. A strange ringing filled the air, which must have been unverifying coming from a deceased loved one. The skull is the worst. Steam builds inside the cranial cavity with nowhere to escape. The pressure climbs. Then the skull pops. The sound is sharp, sudden, unmistakable. It does not sound like wood cracking.

It does not sound like flames. It sounds like a short, wet cry from something that should not be making noise anymore.

Teeth are worse. Teeth shatter. The enamel cannot withstand the heat stress when the interior expands, leading to violent fracture. The fragments scatter from the pyre, blown clear by the force of the break. To a Viking standing near the flames, that was not physics. That was a dead man’s cry.

Now imagine half a body burning unevenly. One leg is exposed to the direct heat, blackening and curling. The torso was still half-covered by wet timber, steaming but not burning. When those bones finally give way, they crack loud enough to make the mourners step back in fear.

When the Fire Refused to Finish

Cremation was never total destruction. Archaeological evidence from across Scandinavia shows that Viking cremations often left far more behind than intended. Studies of over a thousand separate cremation contexts reveal that the total weight of recovered bones usually ranged from a few grams to 100 grams.

A modern cremation yields over three thousand grams. Where did all the rest go? Some was reduced to ash fine enough to blow away. But some simply never burned at all.

At sites throughout Scandinavia, archaeologists have found cremation deposits containing bones that survived as recognisable fragments.

Rain could arrive in the final hour, breaking the heat. A gust could scatter the coals and leave substantial portions of the body intact.

Wind direction, wood quality, body position, the skill of those building the pyre, all of it mattered. Get one thing wrong, and the dead man stayed too whole.

When Things Went Wrong

In various locations across Scandinavia, archaeologists have discovered significant variation in the success of cremation. Some bodies were reduced almost entirely to ash, while others left sizeable fragments: entire vertebrae, sections of skull, and pieces of pelvis.

Rain might arrive in the final hour, cooling the heat. A gust of wind could scatter the coals, and factors like wood quality and the skill in building the pyre were critical. If not done properly, or adverse weather and wind conditions hit, the corpse could remain too intact, and the Norse were familiar with the dangers of the restless dead.

The Animals Who Came to Feed

Burning flesh has a smell that travels for miles. Wolves caught it on the wind. Dogs went mad trying to reach it. Foxes circled at the edges of the light. Howling, barking, and strange bird noises would have filled the air.

The air would have pulsated with the heat. All of this created an eerie atmosphere.

Ravens came down in black clouds, landing in the trees, waiting, watching and chattering loudly. Archaeological evidence shows that animals were drawn to cremation sites, their presence woven into the rituals themselves.

Picture the scene: the pyre blazes, flames towering above a man’s head. A wolf at the tree line howls at the cracking sounds from the fire while the wind carries a low, mournful moan through the stacked logs.

The Night the Living Stepped Away

Wet timber whistles when it burns.

A collapsing layer of logs can drop the body straight through the centre, and when it does, the sudden intake of air creates a sound like a long, drawn-out groan.

The families and slaves would have stepped back in discomfort many times. This was someone they knew.

Howling winds, howling foxes, groans and whistling, peppered by cracking bone, spitting fat, all created a cacophony of strangeness that must have been hard to bear.

It could have sounded as though the dead were protesting.

Every sound has an explanation. Heat. Pressure. Wind. Biology. We know this now. But the Vikings did not have words for thermal fracture or steam expansion. They had memory and fear.

And on those nights when the wind howled fiercely, and the pyre burned wrong, when the skulls split and the wolves answered, and the flames made sounds that should not come from flames, the Vikings probably feared their person did not get to Valhalla.

Valhalla was the great hall of the slain in Norse belief, ruled by Odin and reserved for a particular kind of dead man.

Only those killed in battle and chosen by the Valkyries could enter. The sagas describe Valhalla as a vast hall with spear shafts for rafters and shields for a roof, where warriors spent their afterlife training for Ragnarök.

A burial was a send-off, so it was essential to the people who sent the warrior off. All of this adds a certain tension to the air. One can only imagine.

The Norse prayer hangs heavily in the air:

Lo, there do I see my father; Lo, there do I see my mother and my sisters and my brothers; Lo, there do I see the line of my people, back to the beginning. Lo, they do call to me, they bid me take my place among them, in the halls of Valhalla, where the brave shall live forever.