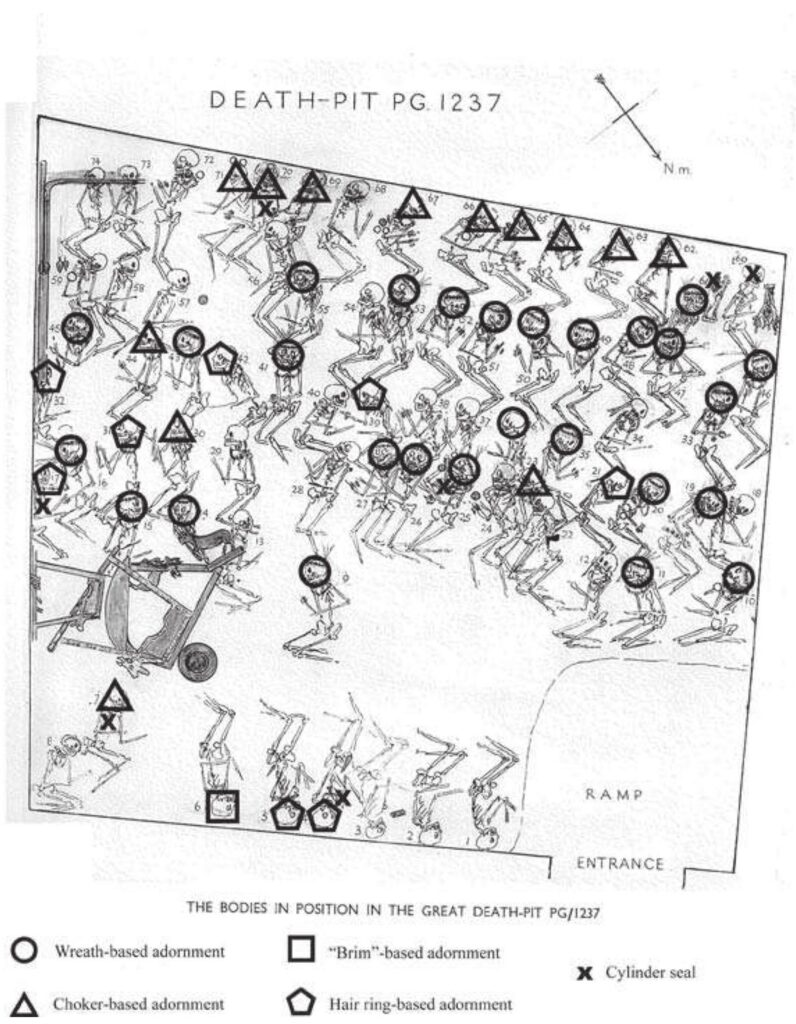

They were found lying in perfect rows beneath the earth at Ur, seventy-four bodies dressed in gold and lapis, arranged with such unnatural precision that the archaeologists knew immediately they had walked into something ritualistic.

The site of what would become known as tomb PG 1237 left archaeologists speechless. Attendants still wore their crowns, the bodies lay in rows, and musicians still rested beside their lyres. There were no signs of struggle. No frantic scrambling. Only a chilling, deliberate stillness that raised the same question again and again. What kind of belief could make so many people walk calmly into death?

When the archaeologists lowered themselves into the earth at Ur, they did not expect silence to feel so heavy. Yet, even within the vast temple complex of the Royal Cemetery at Ur, this tomb felt different.

The soil, heavy with the weight of four and a half thousand years, uncovered something that should not have been there at all. Rows of bodies arranged in a type of order that had a purpose, women dressed in delicate gold headdresses, and several men were also included in this mass grave. It looked less like a burial and more like a frozen moment of ritual death, as if time had stood still. As these people had lived, so had they died. The question rose immediately. Who were these people, and why did they die together in such unnatural calm?

It is a discovery that still makes you feel chilled to the bone and curious about how it all happened in the first place.

You see, the bodies were not thrown or scattered; they were arranged. They rested as if asleep, their jewellery still shining, their vessels placed by their hands, their positions too precise to suggest chaos. There was an eerie serenity about the scene.

These were not victims of an attack or natural disaster. Someone orchestrated this moment. Someone decided that these men and women would accompany their ruler into the afterlife. Why did they agree, and what did they believe awaited them beyond this world?

The First Shocking Finds Of Tomb PG 1237

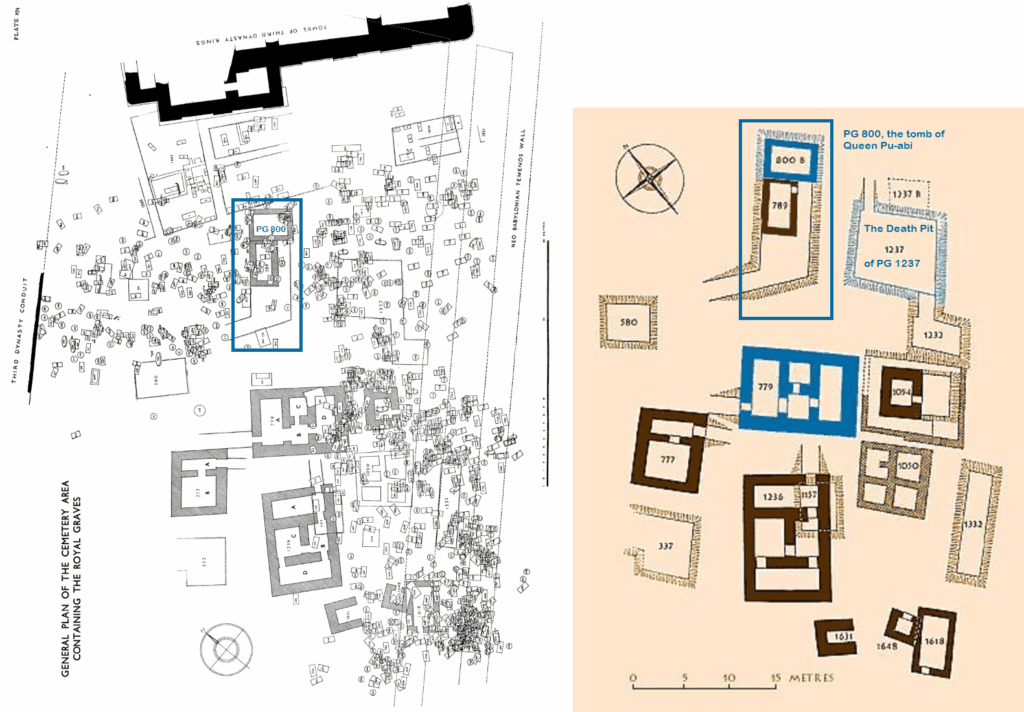

The Royal Cemetery of Ur lies in modern Iraq, once a powerful Sumerian city-state. As one of the cradles of civilisation, it has been a hive of archaeological activity for over a century.

In the 1920s, Sir Leonard Woolley led an excavation that would redefine our understanding of early Mesopotamian ritual. Woolley and his team used carefully laid trench systems, each measured with cords and flagged with grids, to avoid disturbing fragile layers. It was an early version of what would become known as the box-grid method, but Woolley was doing it on a massive scale.

Archaeological methods have evolved since the 1920s, but even back then, Woolley and his team took great care. They recorded each discovery in the meticulous manner now common in archaeology. They took their time with each layer, mapping, photographing, and recording.

Woolley was an experienced archaeologist even before he got to Ur. That experience helped him understand that what he had in front of him at the Royal Cemetery was special, and that tomb PG-1237 stood out.

In total, sixteen royal tombs were found among more than two thousand graves. The famous Death Pits belonged not to soldiers or commoners but to attendants, musicians, guards, and courtly servants. They had lain untouched since about 2600 BC, preserved beneath heavy clay.

Many were discovered still wearing intricate jewellery of gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian. Their adornments were so perfect and so lavish that Woolley could not ignore the most unsettling interpretation. These people had not simply been buried with their ruler. They had died with them. How willingly they met that fate remains one of the most significant debates in archaeology.

How the Death Pits Were Uncovered

The most striking pit, commonly called the Great Death Pit, or tomb PG-1237, held around seventy-four individuals. This consisted of 68 women and six men.

To excavate it without damaging the smallest fragment, the team worked on suspended walkways above the pit so they would not compress or disturb the soil. This was a different approach to excavation compared to other excavations at the time, but it undoubtedly helped preserve most of the archaeology.

Every skull, every bead, every crushed lyre fragment was left in place until its context was documented. Plaster was sometimes poured around delicate objects before removal, allowing them to be safely lifted. Some bodies had collapsed as the wooden litters beneath them decayed over millennia, yet their positions still revealed deliberate arrangement. One could almost picture the original funeral procession.

The excavation process revealed patterns in the deposits. Bronze daggers lay by some bodies. Musical instruments lay by others, including the famous bull-headed lyre that now sits in the University of Pennsylvania Museum. The richer the object, the more certain it became that these attendants were not random victims. They had roles. They had identities. They had status. Something compelled them to inhabit what became an enormous collective grave.

Sumerian Beliefs that Shaped the Ritual

To understand this strange and unsettling practice, one must look at Sumerian beliefs about death. The underworld, known as Kur, was not a paradise. It was a dim and dusty realm where the dead lingered as shades.

But don’t make the mistake of thinking only specific individuals went to Kur and that those who were richer in life would have a better time after death. Nobody could escape going to Kur and its darkness, but there was still something you could attempt to make it easier for you.

Food offerings and remembrance were essential, for without them the dead faded. A ruler of great power required more than offerings. They needed a functioning court in the afterlife.

Servants, musicians, guards, and attendants would continue their duties beyond the grave. The idea was that someone with status in our world deserved to have the same things in the afterlife. Let’s face it, they had to attempt to survive the afterlife, so they had to use any trick in the book.

The Sumerians believed that divine order governed everything and that the gods chose kings. If the king required a whole retinue in the next world, then it followed that these attendants must accompany them. With this in mind, it’s easy to see why people didn’t appear to struggle or fight against joining someone of royal status in the afterlife. To do so would have involved going against not only royalty but the Gods themselves, and nobody would ever dream about doing that.

Whether this was presented as duty, religious honour, or command, we as archaeologists cannot say. Yet the bodies’ arrangement shows a type of acceptance, no struggle, just a decision that it was time to travel on from this earth. No struggles, no fractured bones or violence was detected. This makes the scene all the more disturbing to modern civilisation.

Many scholars believe that a narcotic or poison may have been used, creating a peaceful and coordinated death. The absence of visible trauma strengthens that theory and raises further questions about ritual obedience.

What the Archaeologists Found in Tomb PG-1237

Among the famous objects recovered were the ram-in-a-thicket figurine, gold and lapis jewellery, and the elaborate headdresses worn by royal women.

Although some skulls showed signs of light fractures, these are thought to have occurred after death. Not as a part of the ritualistic burial. The bodies seemed to lie as they had in life; some held cups, some looked relaxed as though lying on their backs. Many had musical instruments ready to play again when required in the next life, of course.

The scene was almost theatrical, as though the dead were placed for a final performance. Why such precision was necessary is still an open question.

Currently, the artefacts are housed in the British Museum in London, the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, and the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad.

Crowds view them without always understanding the human cost behind their beauty. Each gold leaf on a headdress once touched the skin of a woman who believed she was stepping into eternity. Each lyre string belonged to a musician who played their last song before descending into silence. The objects alone cannot tell their story, but the arrangement of the bodies brings the truth closer.

A Tradition Far Older and Wider

Although the Death Pits of Ur are among the most famous examples of mass sacrificial burial, they are not unique.

Across ancient cultures, similar practices emerged. The Egyptians sacrificed retainers in the earliest dynasties. The Scythians buried attendants with their chieftains. The Shang Dynasty in China conducted large-scale human sacrifices.

Even Viking graves sometimes contained sacrificed enslaved people. In each case, the idea was tied to power, identity, and belief in a continued existence in which rulers required service.

Ur stands as one of the earliest and most complete examples, preserved in startling detail.

The practice faded over time as societies shifted towards symbolic offerings rather than human attendants. Changes in belief and religion played a significant role. Growing ethical awareness, centralised laws, and the evolution of social structures reduced the acceptance of ritual killing.

Replacement objects made of clay or wood became substitutes for living servants. As belief systems changed, so too did burials.

The Lasting Question

The Death Pits of Ur are a spectacular archaeological discovery that continues to raise questions about ritual and belief. About religion and how far it can push civilisations. It also questions the value of people’s lives within those civilisations. To know that people who had more were seen as more, and that this decision determined when another person’s life ended. Even if they were travelling to the afterlife.

Each society leaves its legacy, and each society leaves us stories, some told and some seen, like this one at Ur.

Want to Know More About the Psychology of Sacrificing Your Life?

The idea of giving up your life in this manner for others is crazy to us, but there’s psychology behind it. Learn more about what is going on at our Substack.