⚠️ Adult Content Warning: This article includes ancient Roman imagery of nudity and sexual symbols.

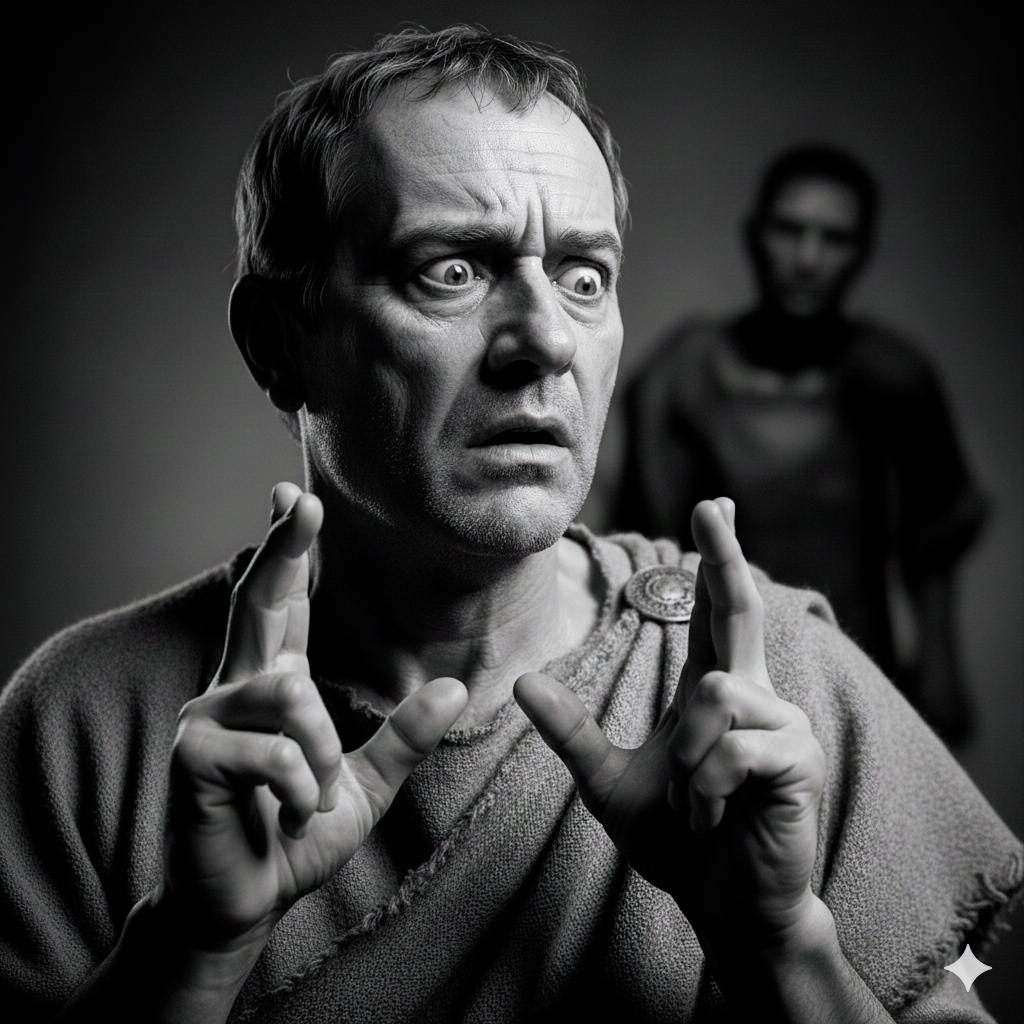

Rome certainly wasn’t built in a day, and Pompeii wasn’t just a city buried in ash. They were both a civilisation and a city obsessed with protection. The Romans lived in perpetual fear of the evil eye, a curse believed to be the result of envy and jealousy. But how the Romans fought curses was wide and varied.

When A Mere Dirty Look Could Cause Havoc

A jealous or hostile look, even a dirty look, they believed, could bring sickness, blight, or even death to the receiver. To defend themselves, Pompeii’s citizens filled their streets and homes with magical symbols designed to repel danger. Archaeologists have uncovered hundreds of examples. Here are three of the most striking from across the Roman Empire:

1. Evil Eye Attack Mosaics

The evil eye wasn’t simply a decoration; it was the enemy itself. Romans believed that jealousy had real, destructive power, so they created mosaics depicting the curse being violently destroyed.

The Eye Blasts Away Bad Luck

One of the most famous examples, from Antioch in Turkey close to the Syrian border, shows a giant eyeball surrounded by attackers: snakes sink their fangs into it, scorpions sting it, dogs lunge at it, and weapons stab it.

A dwarf brandishes a giant phallus, and in some mosaics, phalluses are even shown ejaculating directly into the eye, fertility and life force blasting envy away.

These mosaics weren’t tucked out of sight. They were placed right at the thresholds of houses, forcing every visitor to walk across the “curse under attack” before stepping inside. Not exactly the sort of artwork you’d hang in your living room today.

2. “Cave Canem” — Beware of the Dog

At the entrance of the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii lies one of the city’s most famous mosaics. Set into the floor, it shows a fierce, chained watchdog with the words CAVE CANEM, “Beware of the Dog.”

To modern eyes, it is a simple warning sign against burglars. But in Roman belief, dogs carried supernatural weight. They were guardians of thresholds, loyal protectors, and creatures tied to the underworld.

By embedding the image permanently into the floor, the homeowner gave their household a magical guardian: every guest, and every spirit had to pass across the protective dog before entering.

A giant dog’s face at your doorway wouldn’t chase robbers away, but in Pompeii, it was deadly serious.

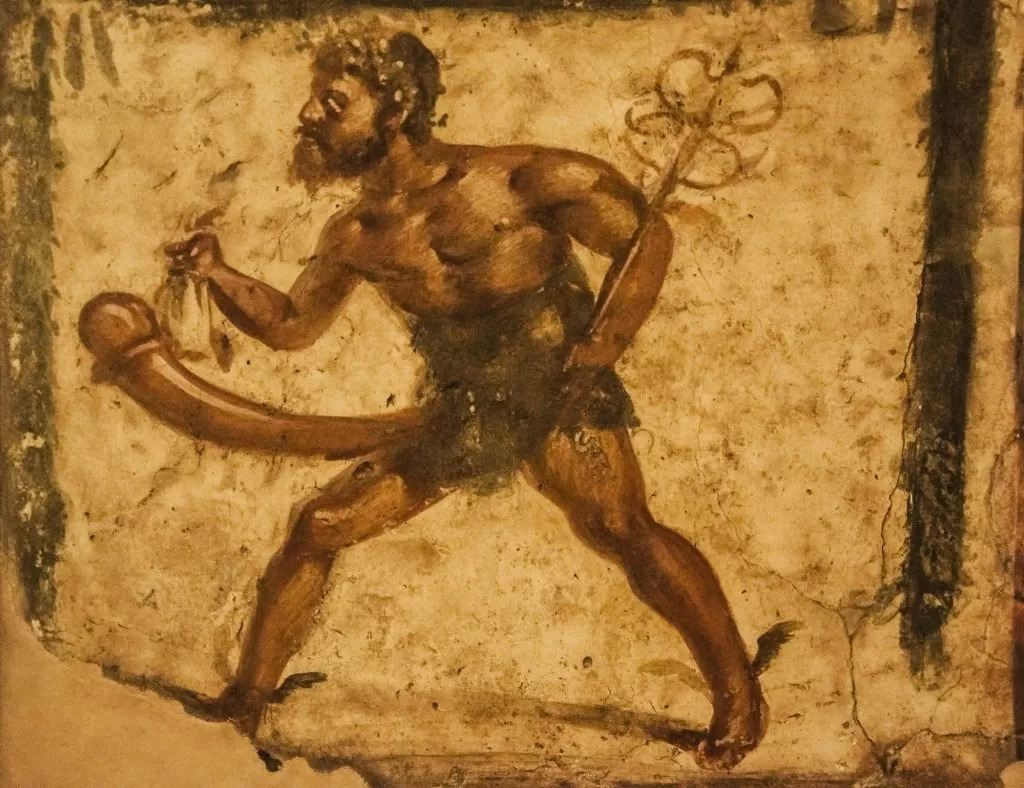

3. Phallic Symbols Everywhere

Pompeii is scattered with phallic imagery. Stone phalluses were carved into walls, scratched into paving stones, painted above doorways, and sometimes cast in bronze.

Small bronze wind chimes in the shape of phalluses, called tintinnabula, were especially common, designed to jingle in the breeze and ward off evil with their movement and sound.

To the Romans, the phallus wasn’t obscene; instead, it was a symbol of fertility, prosperity, and, most importantly, protective power. Displaying one was thought to ward off envy and keep curses at bay.

In a city where daily life was shadowed by the fear of the evil eye, these symbols served as everyday security, much like our modern security. Security measures.

Nothing says “welcome home” quite like a bronze penis jingling in the hallway.

Conclusion

Pompeii’s ruins don’t just show us streets, houses, and bathhouses frozen in time. They reveal a city that lived in constant dread of curses, and that fought back with mosaics of eyeballs under attack, magical guard dogs, and protective phalluses carved into the very stones of the street.

The people of Pompeii may have guarded themselves against envy and evil spirits, but none of their protections could withstand the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79.

Sources

- Beard, Mary. Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town. Profile Books, 2008.

- Clarke, John R. Looking at Laughter: Humour, Power, and Transgression in Roman Visual Culture. University of California Press, 2007.

- Pompeii Archaeological Park: House of the Tragic Poet (Cave Canem mosaic).

- British Museum: “Tintinnabula and Phallic Imagery in Roman Culture.”